Christopher Columbus. Admiral of the Ocean Sea. The Great Navigator. Renown as the champion of the belief that the earth was round. The man who sought the riches of the Far East by sailing to the west, and who happened instead upon a New World. The man who discovered America. How accurate is the portrait of Columbus that is painted today?

Where did Columbus really set foot on the New World? Theories and sites abound.

by William F. Keegan

Originally published in VISTA magazine, October 6, 1991.

To read Columbus’s daily log (diario de a bordo) you would think that his small fleet was never very far from land. For 32 days after leaving Gomera in the Canary Islands on September 9th, the diario makes repeated reference to signs of land. Sailing in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean, more than 1,000 miles from the nearest land, Columbus observed “river weed” (sargassum seaweed), a live crab “not found more than 80 leagues (240 miles) from land,” a booby or gannet, birds that “do not depart more than 20 leagues from land,” and “a large cloud mass, which is a sign of being near land.” But it was not until two hours after midnight, the 12th of October, that land finally did appear.

The land was an island, which the native Lucayans called Guanahani, and Columbus renamed San Salvador (“Holy Savior”). Scholars agree that Guanahani is in the Bahama archipelago, but that is where agreement ends. To date, ten different islands have been identified as the first landfall; a truly remarkable number when you consider that only 20 islands in the entire archipelago are even remotely possible candidates. In addition, more than 25 routes have been proposed to take Columbus to the three other Lucayan islands he visited before departing for Cuba. Represented on a single map these routes look like someone gone mad playing connect the dots.

Cat Island, in 1625, was the first to be proposed as the landfall island. Cat went unopposed until Watling Island was suggested in 1793. Grand Turk was next, followed by Mayaguana, and Samana Cay in time for the 400th anniversary in 1892. Cat Island’s claim was ably defended by the novelist Washington Irving (“The Legend of Sleepy Hollow”), while Watling was promoted by the Chicago Herald (site of the Columbian Exposition in 1893), and Samana was championed by Gustavus Fox who served as Assistant Secretary of the Navy under President Abraham Lincoln.

In 1926, Cat and Watling entered a legal battle over who had the right to use the name San Salvador. The case was settled by the Bahamas legislature in favor of Watling. Known legally as San Salvador ever since, Watling gained its strongest support from the distinguished Harvard Historian Samuel Eliot Morison who retraced Columbus’s steps in his 1942 Pulitzer Prize winning biography of Columbus. Morison’s reconstruction seemed to end the debate once and for all.

Other first landfall islands have been suggested since — Conception (1943), East Caicos (1947), Plana Cays (1974), Egg/Royal (1981), Great Harbour Cay (1990) — but none has made a sufficiently strong case to sway popular opinion away from Watling. None, that is, until 1986 when National Geographic magazine told 40 million readers that Samana Cay was the place.

But why the debate? Why hasn’t Guanahani been identified with certainty? The answers lay in the quality of the evidence. The only detailed information concerning Columbus’s first voyage is contained in his diario. Columbus presented the original to Queen Isabel who had a copy made for Columbus. The whereabouts of the original are unknown, and all trace of the copy disappeared in 1545. What has survived is a copy made by Bartolomé de las Casas — a thirdhand manuscript handwritten in sixteenth-century Spanish that has numerous erasures, unusual spellings, brief illegible passages, and notes in the margins. The ambiguities, errors, and omissions in this manuscript have been compounded in modern-language translations.

Putting such problems aside for the moment, what of that account might be used to identify Guanahani? Arne Molander, an advocate of Egg/Royal Island, has identified 99 clues, many of which require specialized knowledge and most of which are subject to multiple interpretations. Such minutia are beyond the scope of this brief article, instead let us consider four general categories: ocean crossing, descriptions of the islands, sailing directions and distances, and cultural evidence.

Using a computer generated simulation of the first voyage that took into account prevailing winds and currents, the National Geographic team concluded that the crossing ended at Samana Cay (actually, they overshot Samana by more than 300 miles and had to shorten their league by 10% to land at Samana). When a team from Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution substituted average for prevailing winds and currents, their simulated crossing ended in sight of San Salvador (without need to adjust for distance). However, not satisfied with that solution, this same team plugged new numbers into their computer and put Columbus near Grand Turk! Too bad, as one reviewer noted, Columbus didn’t have a computer on board.

A different approach to the crossing is to simply use Columbus’s statement that Guanahani was on the latitude of Ferro in the Canary Islands. Simple enough? Latitude sailing was certainly possible in Columbus’s day, and Arne Molander has shown that the latitude from Ferro crosses Egg Island, just north of Eleuthera. However, Robert Power, armed with maps of the day, has shown that the Americas are consistently displaced northerward on these maps and that in sixteenth-century cartography the line from Ferro crosses Grand Turk. In this way both northern and southern Bahamas landfalls have been supported.

The situation does not improve when you move to descriptions of the islands themselves. For example, prospective Guanahanis range in size from 10 to 389 square kilometers, the harbor that could hold “all the ships in Christendom” from .6 to 36.6 square kilometers, and the second island is either 5 by 10 leagues (as recorded in the diario) or 5 by 10 miles (a likely transcription error).

If we cannot be certain what he was describing, then we should at least be able to retrace how he got there. Yet the record of directions and distances has been used to defend more than 25 different routes. The most basic disagreements concern translation; such as whether camino de should be translated as “the way from” or “the way to.” More complicated disagreements arise over interpolations. Between the night of October 17th and the morning of the 19th one route has the fleet sail fewer than 20 miles, while another has them cover more than 300. The first claims that bad weather prevented them from sailing on the 18th while the latter claims that storm winds propelled the three ships at breakneck speed.

Lastly, Columbus visited four native villages and spent three days trying to reach the village of a chief. I have used archaeological evidence to show that the Watling to Rum Cay to Long Island to Crooked Island to Cuba route best fits all of the data. Others, however, believe that there were so many Lucayans living in the Bahamas that virtually every route will find archaeological sites in the places where Columbus observed villages. Only more archaeology will tell.

Where was Columbus’s first landfall in the Americas? The Lucayans called the island Guanahani, and Columbus renamed it San Salvador. In my opinion it is known today by the name Columbus gave it.

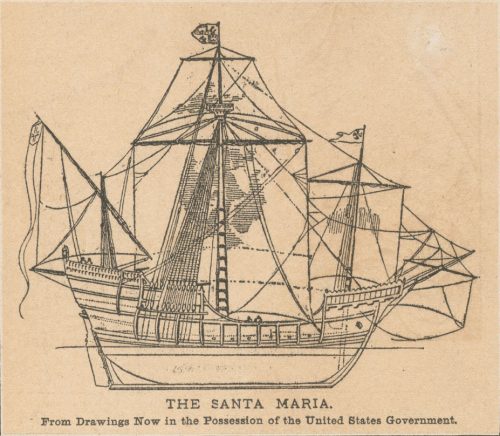

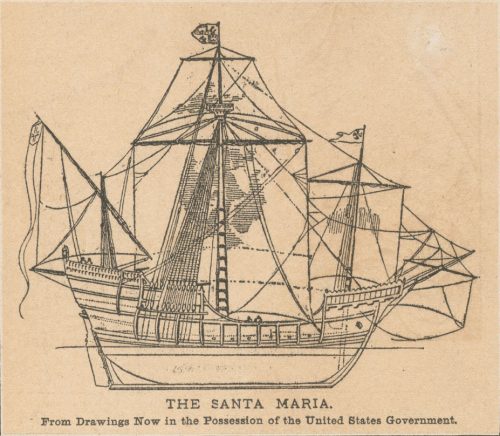

Small and feeble, the ships of Columbus opened a route to an unknown world.

by William F. Keegan

Originally published in VISTA magazine, July 7, 1991

“We departed Friday the third of August of the year 1492 from the bar of Saltés at the eighth hour,” thus begins the daily log of Christopher Columbus. There had been no fireworks, no fanfare as the Santa Clara, Pinta, and La Gallega departed the port of Palos on the Río Tinto half an hour before sunrise. Columbus was aboard La Gallega, the largest of the three vessels. Originally named for Galicia, the town in which she was built, she was known to her sailors as “Marigalante,” literally “dirty Mary.” Columbus rechristened her Santa María. The others were also known by nicknames: Santa Clara, was known as Niña (“little girl”) a play on the name of her owner, Juan Niño; Pinta means “painted one.”

The expedition was a community enterprise. The Niña and Pinta were outfitted with supplies and crew by the citizens of Palos and Moguer in payment of a fine imposed by the Crown “for some things done and committed.” Two of the areas leading families, Pinzón and Niño, headed the expedition. The crews were not the faint-hearted landlubbers and criminals of legend who became frightened during a long expedition and who threatened mutiny until calmed by Columbus. There was no mutiny. These were men with years of shared experience, knowledge of the sea, and confidence in their abilities. As Professor Carl Sauer noted in The Early Spanish Main: “Columbus had originated and promoted the idea of the voyage; Spanish seamen made it possible and carried it through.”

That is not to say that Columbus heard no complaints. There were royal representatives and freed criminals aboard Santa María. Moreover, she was an uncomfortable vessel; a slow, tubby, ship-rigged cargo carrier on which Columbus had the only private space — a 10 by 20 foot room under the poop deck in the back of the ship, which had small windows on either side and a door in front. Luxurious accommodations on a ship whose deck space, roughly the size of a modern tennis court, was shared by a 40 man crew.

Santa María was a “nao,” slightly larger and more round-bellied than the two caravels, Columbus described her as “very heavy and not suitable for the business of discovery.” Santa María sank on Christmas eve near Cap Haïtien, Haiti, the first of nine ships that would sink during Columbus’s explorations (four at La Isabela, 1495; two in Panama, 1503; two in Jamaica, 1504).

The other two vessels were “caravels,” a name used to describe a variety of relatively small ships of 70 to 80 feet in length having a capacity of 60 to 70 tons. Caravels reflected several major improvements in ship design, specifically, a change from single-masted square rigging to multiple lateen sails (large triangular sails that improved maneuverability into the wind), the use of pre-constructed framing upon which flush, end-joined (‘carvel’) planking was nailed, and the use of a stern-mounted rudder as opposed to traditional side-mounted steering oars. Caravels had one deck, no forward structure, and only a modest raised poop deck and transom stern. Because ships of the day were built of individually crafted pieces without benefit of plans or drawings, we cannot be certain of the exact dimensions of the Niña or Pinta. However, Professor Eugene Lyon has uncovered records pertaining to Columbus’s 1498 expedition in which the Niña took part. Lyon concluded that Niña was 67 feet long, 21 feet wide, seven feet draft, and a capacity of 52 tons.

By modern standards the ships were overcrowded, the Niña and Pinta carried 25 man crews, especially on the first transatlantic voyage which did not make port between September 6th and October 12th. With only one cabin below the poop deck, the crew spent most of the voyage exposed to the elements. At night they had the option of sleeping on deck or below deck on the ballast pile where cargo, the main anchor, and heavy armaments were stowed. The favorite place to sleep was the hatch covers, the only level spots on the ship. The adoption of hammocks from the native peoples of the West Indies revolutionized sleeping aboard ship.

Although most expeditions expected to make port within two weeks, Columbus’s three ships carried provisions for an entire year. Records of the 1498 voyage of the Niña listed stores of wheat, flour, wine, sea biscuit, olive oil, garbanzos, cheese, salt pork, vinegar, fatback, sardines, and raisins. Cooking was done on deck in large copper kettles over a fire in a sandbox kindled with vineshoots and fed with olivewood.

Because there is little mention of weapons in the earliest chronicles, most naval historians have concluded that the ships were not well armed. The work of Donald Keith, Director of Ships of Discovery, and other nautical archaeologists, has challenged that view. Dr. Keith reports that the earliest Caribbean shipwrecks have well-formed batteries of armament. For example, the Molasses Reef wreck, a late 15th to early 16th century Spanish wreck in the Turks and Caicos Islands, carried “ship-killing” wrought-iron cannons called bombardetas and a cerbatana; three types of versos, swivel guns mounted on the “gunwale” (hence the name) which were useful for raking the decks of enemy ships or keeping unfriendly canoe-borne Indians at bay; smaller swivel guns called harquebuts which could be mounted on the ship’s boats during amphibious assaults; and a variety of portable arms including rifles (arquebuces), crossbows, lances, swords, and even hand grenades. These weapons show a sophisticated appreciation of guns and range of shot. Even though we cannot specify their effects, they were a key element in the conquest of the Americas.

These were not, however, warships. The warships of the day were galleys, long, sleek vessels driven to sea by an oversize lateen sail and then propelled into battle by scores of oarsmen. Their bows were constructed as battlefields with a battering ram leading the way below an artillery platform, from which large caliber cannons fired scrap metal, and a boarding platform from which archers, musketeers, and swivel gunners attacked the enemy from close range.

The ships of exploration were general-purpose cargo vessels (investors were reluctant to risk first class ships). They were uncomfortable and were not made for the business of discovery, yet their maneuverability, their flexibility of rigging, their ability to travel more than 100 miles per day under favorable conditions, and to sail in shallow water gave them a major role in voyages of exploration. In the words of Dr. Roger Smith, underwater archaeologist for the State of Florida, caravels were the “Mercury spacecraft of a long line of transoceanic vessels.”

It was only after the major discoveries of the sixteenth century had been completed that a new vessel was created for the purposes of transoceanic commerce. This new ship was the famed “galleon.” Designed in response to the need for speed and security, galleons combined the cargo capacity of the nao, the sleek water lines of the galley, and the sail patterns and rigging of the caravel.

Pequeñas y débiles, las naves de Colón abrieron ruta hacia un mundo incógnito.

by William F. Keegan

Originally published in VISTA magazine, July 7, 1991

“Zarpamos el viernes, tercer día de agosto del año 1492, a la octava hora,” comienza el diario de Cristóbal Colón. No hubieron ni fuegos artificiales ni fanfarrias cuando la Santa Clara, la Pinta y la Gallega salieron del puerto español de Palos, por el río Tinto, media hora antes que despuntara el sol.

Colón viajaba en la Gallega, la mayor se las tres naves, apodada por sus tripulantes “Marigalante” — María la disoluta. Colón la rebautizó Santa María. Las Otras naves también tenían apodas. A la Santa Clara se le conocía como la Niña, porque el dueño era Juan Niño; Pinta significaba “la pintada.”

La expedición era una empresa comunitaria. La Niña y la Pinta llevaban víveres y tripulación suministrados por las ciudades de Palos y Moguer, en pago de una multa impuesta por la Casa Real de España. Miembros de las familias principales de la región, Pinzón y Niño, estaban al mando.

Los tripulantes no eran los medrosos ciudadanos que, según la leyenda, se amotinaron durante la larga expedición. No hubo tal motín. Estos eran hombres con años de experiencia, conocimiento del mar y confianza en sus habilidades. Como anotó el Professor Carl Sauer en Los Comienzos de la Armada Española, “Colón originó y promovió la idea del viaje. Los marineros españoles la hicieron posible y la ejecutaron.”

Esto no quiere decir que Colón no escuchó quejas. A bordo de la Santa María iban agentes de la Corona y criminales liberados. Era una “nao” (barco de transporte) regordeta, lenta, incómoda, donde Colón gozaba del único espacio privado: un camarote de 10 por 20 pies, bajo el puente de popa, con ventanillas a cada lado. Lujosa cabina ésta, en un barco cuyo espacio habitable — aproximadamente del tamaño de una cancha de tenis — era compartido por 40 tripulantes.

La Santa María era más grande que las carabelas, “muy pesada,” según Colón, “y no apropiada para el negocio de descubrimientos.” Se hundió esa Nochebuena cerca Cap Haitien, Haití, la primera de nueve naves de Colón que naufragaron durante sus expeciciones (cuatro en La Isabela, 1495; dos en Panamá, 1503, y dos en Jamaica, 1504).

Los otros dos navíos eran carabelas, barcos relativamente pequeños, de 70 a 80 pies de eslora (largo), con una capacidad de 60 a 70 toneladas. Las carabelas incorporaban varias mejoras en el diseño náutico, principalmente un cambio en las velas, de cuadradas a triangulares, que daban mayor maniobrabilidad. Tenían una cubierta, un modesto puente de proa. Se maniobraban con un timón montado a popa, no con los remos tradicionales. Sus costillas eran preconstruídas; las tablas se clavaban sobre ellas cabo a cabo, en estilo “carabelado.”

Ya que los barcos de ese tiempo se construían sin uso de planos, no se conocen las dimensiones exactas de la Niña o de la Pinta. Sin embargo, el historiador Eugene Lyon ha descubierto archivos referentes a la expedición de Colón de 1498, en la que tomó parte la Niña. Lyon, un profesor de la Universidad de Florida, deduce que la Niña medía 67 pies de eslora, 21 de manga (ancho), 7 de calado (espacio bajo la línea de flotación) y que tenía una capacidad de 52 toneladas.

Con una tripulación de por los menos 20 marinos cada una, no cabe duda que la Niña y la Pinta estaban repletas. Con sólo una cabina abierta en la popa, los navegantes pasaban la mayor parte del tiempo a la intemperie. Por las noches, podían dormir sobre cubierta o en la estiba, junot a la carga, el lastre y los armamentos. Los lugares favoritos para dormir eran las cubiertas de las escotillas, las únicas superficies planas en la nave. Las hamacas descubiertas más tarde en el Nuevo Mundo, revolucionaron el estilo de vivir de los marineros.

Aunque la mayoría de los expedicionarios preveían entrar a puerto en dos semanas, los tres veleros de Colón llevaban provisiones para un año entero. El manifiesto de la Niña en 1498 indicaba cantidades de harima, trigo, vino, galletas, aceite, grabanzos, queso, puerco salado, vinagre, tocina, sardinas y pasas. El cocinero laboraba sobre la cubierta usando grandes ollas de cobre. Troncos de olivo ardían en una caja de arena, bajo las ollas.

Porque los relatos antiguos poco mencionan las armas, muchos historiadores han llegado a la conclusión que las naves no estaban bien apertrechadas. Donald Keith y otros expertos náuticos han corregido esa impresión al estudiar el armamento de naves hundidas en el Caribe. Un buque naufragado entre los siglos XV y XVI en las aguas de Turcos y Caicos portaba: Cañones de grueso calibre llamados bombardetas y una cerbatana; tres tipos de versos, cañones giratorios montados en la balaustrada; cañones giratorios pequeños, llamados harquebuts, que podían montarse en las lanchas para ataques anfibios; y una variedad de armas de mano, incluyendo arcabuces, ballestas, lanzas, espadas y granadas. Esta fuerza bélica fue un elemento clave en la conquista de las Américas.

Las naves de Colón no rean sin embargo, buques de guerra. En su mayoría fueron veleros de carga, cuya maniobrabilidad, capacidad para navegar más de 100 millas diarias bajo condiciones favorables y para surcar aguas poco profundas les dieron un papel importante en los viajes de exploración.

Las carabelas, dice Roger Smith, arqueólogo marino para el estado de Florida, eran “las astronaves Mercury de una larga línea de navíos transoceánicos.”

500 years after his epoch-making trip, The Great Navigator remains an enigma.

by William F. Keegan

Originally published in VISTA magazine, March 24, 1991

Christopher Columbus. Admiral of the Ocean Sea. The Great Navigator. Renown as the champion of the belief that the earth was round. The man who sought the riches of the Far East by sailing to the west, and who happened instead upon a New World. The man who discovered America. Removed from Hispaniola in chains in 1500 and wrongly persecuted in his later years. His story typifies that of a tragic heroic figure.

Yet how accurate is the portrait of Columbus that is painted today? How much of what we know comes from the deification of a long-dead hero whose personal attributes have been shaped to reflect the greatness of his discoveries? And how much of what we are being told today is simply a revisionist backlash that demands attention by attacking dead heros?

A century ago Columbus was a hero who was feted in the Columbian world expositions as a man whose single-minded pursuit of his goals was to be emulated. Today he is being reviled as a symbol of European expansionism, the forbearer of institutionalized racism and genocide who bears ultimate responsibility for everything from the destruction of rainforests to the depletion of the ozone layer. Impressive accomplishments for someone who died five centuries ago.

When one peels back the shroud of myth that today surrounds him we find that his portrait embodies a period of history more than an individual man. Professor Robert Fuson, a Columbus admirer, described him as a man of the Renaissance, whose sensibilities were still firmly rooted in the Middle Ages.

An example of the Columbus mythology illustrates those points. Columbus is often credited with being the first to accept that the earth was round. Yet this fact was first proved by the Greek mathematician Pythagoras in the 6th century B.C. Moreover, when Columbus obtained contradictory navigational readings off the coast of South America during his third voyage in 1498, he quickly abandoned his round earth. Instead he proposed that the earth was shaped like a pear with a rise “like a woman’s breast” on which rested the “Terrestrial Paradise” (Garden of Eden) to which no man could sail without the permission of God. To his detractors, such beliefs are those of a mentally unbalanced religious fanatic; to his promoters, they are remarkably prescient (the earth does in fact bulge along the equator) and they illustrate his steadfast and consuming faith in God.

Beyond historical attributes, his personal characteristics and life history add to the intrigue. What was his real name? Kirkpatrick Sale notes the following possibilities: Christoforo Colombo, Christofferus de Colombo, Christobal Colom, Christóbal Colón, and Xpoual de Colón. Columbus himself, after 1493, chose to sign himself Xpo ferens, which glosses as “the christbearer.” As St. Christopher had before him, he saw himself fulfilling God’s plan by bringing Christ to a new world.

His place and date of birth are also uncertain. He was a Virgo or Libra (he was versed in Astrology), born between August 25th and October 31st, 1435 to 1460, with 1451 the most frequently given year. He claims to have been born in Genoa, although Chios (a Greek island that was a Geonoese colony), Majorca, Galicia, and other places in Spain have also been suggested. Wherever his place of birth, he seems to have thought of himself as a Castilian, the language in which he wrote.

His son Fernando described him as having a reddish complexion, blonde hair (white after age 30), blue eyes, an exceptionally keen sense of smell, excellent eyesight, and perfect hearing. A man of relatively advanced age in 1492 (at least forty years old) the description of him as having been in perfect physical condition must be an exaggeration. He was also reported to be moderate in drink, food, and dress and never swore!!

He was of the Catholic faith, although some claim a Jewish background on one side of his family. He expressed his faith in his choice of a Franciscan friar’s robes for an appearance before the Spanish Court, in leaving his son at the Franciscan monastery of la Rábida between 1481 and 1491, and in his eschatological Libro de las profecías, an array of prophetic texts, commentaries by ancient and medieval authors, Spanish poetry, and Columbus’s own commentaries.

He is said to have gone to sea at age 14. On the Atlantic coast to the north he made at least one voyage to England and possibly one to Iceland, while to the south he sailed as far as the Gold Coast of Africa. He is reputed to have been involved in a naval engagement between Franco-Portuguese and Genoese fleets in 1476. He made four voyages to the New World. Until recently, anything about Columbus character, except his skills as a mariner, was open to criticism. Recently, revisionist historians are unwilling to grant even that. Kirkpatrick Sale claims that Columbus never commanded anything larger than a rowboat prior to the first transatlantic crossing. Yet it remains a fact that he succeeded in crossing the Atlantic Ocean and, more important, he returned safely. It was Columbus’s voyage that set the stage for European expansion.

Columbus married Doña Felipa Perestrello e Moniz in 1479, and their son Diego was born in 1480 in the Madeira Islands. Doña Felipa died sometime between 1481 and 1485, after which Columbus consorted with Beatriz Enríquez de Arana. A second son, Fernando, was born to Beatriz in 1488. While Governor of Hispaniola, he was assisted by his younger (or older) brother (or uncle) Bartholomew Columbus. Christopher, Bartholomew, and their other brother Diego, were arrested in July, 1500, for mismanagement of the colony. They were sent to Spain in chains in October and released in December of that year.

As one looks behind the historical facade that has been built to represent the “discoverer” or “destroyer” of America, one encounters many more questions than answers. The story seems to begin with Columbus seeking financial sponsorship for a voyage to Asia and the Indies. But was Asia really Columbus’s objective? Henry Vignaud and others have maintained that Columbus pursued more personal goals. Upon reaching the islands Columbus spent two weeks searching for gold in the Bahamas. Why did he waste time in the Bahamas when his stated objective lay a short distance to the southwest? Why did Columbus bring trinkets for trade if the gold of the Grand Khan (in Latin “king of kings”) was his primary objective? Why did Columbus claim lands for the Spanish Crown, and himself as the Crown’s representative, if these belonged to an Asiatic Kingdom? Why is there no mention of Asia or the Indies in the titles awarded to Columbus by his royal sponsors?

Christopher Columbus died on May 20, 1506 in Valladolid, Spain of age-related causes. He was about 54 years old. Even in death Columbus left us wondering — Sevilla, Santo Domingo, and Havana all claim to be his final resting place. A fitting twist to the end of his story.

For 500 years there has been only one answer to the question, who was Columbus?

That answer is another question. Who do you want him to be?

If Columbus didn’t get here first, who did?

A historian rounds up the usual—and unusual—suspects.

by William F. Keegan

Originally published in VISTA magazine, September 8, 1991

Marco Polo’s travels in Asia, and Portuguese expansionism in Africa, bear testimony to how little fifteenth-century Europeans knew about their neighbors. It is generally assumed that they knew even less of the continents that lay across the great oceans. In the 2nd century A.D., the Hellenistic scholar Claudius Ptolemy drew a map of the world that would survive until Columbus’s voyage. He depicted the world as a northern hemisphere comprised of a single Euro-Asian continent and northern Africa. The Americas were not depicted. Yet if various avocational historians are to be believed, the American continents had been known for almost two millennia.

Christopher Columbus is credited with the first successful round-trip transatlantic voyage, but even his priority has been questioned. In his day it was rumored that he simply followed a course disclosed to him by a Spanish sailor who died shortly after completing the circuit in 1484. Another story is that the King of Portugal told Columbus of trade between Africa and the Americas — a route that the Mandingo traders from Guinea had somehow managed to keep quiet for more than 150 years. Whether or not such expeditions took place, the Old and New Worlds were poised for contact by the close of the fifteenth century.

English fishermen from Bristol were fishing on the banks off Newfoundland by the 1490s, and John Cabot, sailing for England, reached northern North America in 1494 and cruised the coast of New England in 1497. The Portuguese were also capable mariners whose attempted crossings at the middle latitudes failed because the winds ceased a short distance out into the Atlantic. Their discovery of Brazil would have occurred even if Columbus had never sailed. The fastest course for rounding Africa is to follow the counterclockwise circulation of winds in the southern hemisphere. By sailing first toward Brazil, the Cape of Good Hope could be rounded with a following wind.

But what of encounters before the fifteenth century? The only well-documented case is that of the Vikings. The Norse established colonies on Iceland (A.D. 874), Greenland (A.D. 986), and Newfoundland (by A.D. 1000). An archaeological site called L’Anse aux Meadows has been identified as the short-lived Newfoundland colony. The dates for the site correspond to Norse sagas about Leif Ericson’s Vinland colony. The site was occupied for only a few years, apparently due to hostilities with the Native peoples. The Greenland colony was abandoned shortly after in the face of a deteriorating climate, the end of supply voyages from Europe, and hostilities with the Inuit.

But even Leif Ericson was a late-comer in the northern latitudes according to some. Irish legend holds that in the 6th century A.D. Saint Brendan sailed an oxhide boat westward over the ocean to “where God ruled supreme.” Evidence for the Brendan voyage is an apocryphal Latin text, and a recent recreation of the voyage. Furthermore, according to Harvard Biology Professor Barry Fell, King Woden-lithi of Norway established a permanent trading colony on the St. Lawrence River near Toronto in 1700 B.C. Evidence for this Bronze Age colony is a series of inscriptions in the bedrock that Fell likens to an early Scandinavian alphabet. The supposed colony was abandoned as the climate turned colder at the close of the Bronze Age.

All proposals concerning early trans-oceanic contacts use the same form of argument. Superficial similarities in materials (be they Olmec heads, symbols carved in rocks, pyramids, or even religious and social practices) are identified and are then explained as resulting from contacts (diffusion) between the areas. The distance separating these areas and the mode of transportation between them are rarely important concerns. [An early diffusionist argument had people walking across Antarctica to reach South America!]

Egypt provides an excellent example of how diffusionist arguments work. In the 1920s the distinguished anatomist Grafton Elliot Smith proposed the Pan-Egypt theory, which stated that civilization arose only once, in Egypt, and then spread across the globe. One part of this theory had civilization carried across the oceans by Phoenicians searching for the Egyptian Sun stone, gold. The theory was based on superficial resemblances between such things as Egyptian, Cambodian, and Aztec pyramids, and ignored often dramatic differences. In the final analysis all of the evidence points to independent origins and distinct sequences of development for these cultures.

The second involves demonstrating that contact, often against all odds, was possible. Thor Heyerdahl’s Ra expeditions showed that Egyptians could have crossed the Atlantic in reed boats and that Americans could have sailed reed boats to Polynesia. Likewise, Tim Severin showed that St. Brendan could have crossed the Atlantic in an oxhide curragh. Such recreations have demonstrated that people with a simple maritime technology could have successfully crossed expanses of ocean. They demonstrate what could have been, but can never prove what was.

A final case for Atlantic crossings was proposed on the basis of superficial resemblances between the physical appearance of black Africans and artifacts of the Olmec culture of Gulf-coast Mexico. According to Rutgers Professor Ivan Van Sertima, the Olmec’s colossal stone heads, terracotta sculptures, skeletal remains, and pyramids, along with ancient European maps, all point to contacts between Africans and Central Americans between 800 and 600 B.C.

On the Pacific coast, it is possible that Polynesians reached the Americas. Having succeeded in sailing between islands separated by more than 1000 miles of open ocean, it is reasonable to assume that they could have made the relatively short water-crossing to reach the Americas.

In addition, archaeologists working in Ecuador have noted a number of similarities in the decorations on pottery from the Valdivia site and from Jomon in Japan. Jomon pottery is among the earliest in the world (circa 5000 B.C.), and Valdivia pottery (circa 3000 B.C.) is among the earliest in the Americas. On the basis of this coincidence it was proposed that pottery making was introduced into the Americas by Asians. Earlier pottery-bearing sites away from the coast make an Asian source both less likely and unnecessary.

Speculations concerning contacts between widely dispersed peoples, captures the imagination and challenges conventional wisdom. However, with the exception of Leif Ericson’s colony, pre-Columbian contacts between the Americas and Asia, Africa, or Europe have not been proved. And though Christopher Columbus was certainly not the first to “discover” the Americas, he was definitely the last.

by William F. Keegan

Published in VISTA, November 3, 1991

It has been called the Grand Fleet by Samuel Eliot Morison. Seventeen ships, 1500 men, horses, pigs, beasts of burden; almost everything that would be needed to reproduce an Iberian homeland in what had been described as an earthly paradise. In reporting his discoveries to the crown, the Admiral himself had described the Tainos and their islands in these words: “I believe that in the world there are no better people or a better land.”

On this, Columbus’s second voyage, the fleet had taken a faster more-southerly route. Hurried by the desire to reach and resupply the fort, La Navidad, which he had established eleven months earlier, Columbus cruised the length of Puerto Rico’s south coast in a single day (November 19th). The next two days were spent collecting food and water while the fleet lay at anchored in Boquerón Bay on this island the native peoples called Boriquén and Columbus renamed San Juan Bautista (Saint John the Baptist).

This day he was sailing to the west with the trade winds. How different from the previous year when, on December 6, 1492, the Santa María and Niña approached an island that the Bahamian and Cuban Tainos aboard his ship called Bohío, and which Columbus renamed La Ysla Española (the Spanish Island). Stalled by contrary winds, the two ships had been visited by hundreds, and on one day more than a thousand, Tainos who came in canoes or who swam to the ships. The rulers (caciques) of the villages and provinces (cacicazgos) along the north coast competed with each other to make their invitation to Columbus the most inviting. Yet in the end, the competition was decided by an act of God.

On Christmas day, shortly past midnight, the Santa María had her belly ripped open on a coral reef. Awakened by this explosion, which could be heard “a full league off” (about 3 miles), Columbus ordered the main mast cut away to lighten the vessel. He also sent Juan de la Cosa, the ship’s master, to take a boat in order to cast an anchor astern. Instead, Cosa fled to the Niña, whose captain refused to let him board and who sent his boat to aid the Admiral. It was too little too late; the Santa María was stuck fast.

The wreck occurred in the vicinity of present-day Cap Haïtien, in the Taino province of Marien, which was ruled by a cacique named Guacanagarí. On learning of the wreck Guacanagarí wept openly and he sent weeping relations to console Columbus throughout the night. Afraid to risk the Niña in salvaging the Santa María, Columbus enlisted Guacanagarí’s assistance. His people recovered everything, including planks and nails, and assembled the materials on the beach. So thorough were the Tainos that not a single “agujeta” (lace-end or needle) was misplaced.

Columbus took the sinking of the Santa María as a sign from God that he should build a fort in this location. Guacanagarí gave Columbus two large houses to use. With the assistance of his people, the Spaniards began construction of a fort, tower, and moat in the cacique’s village using the timbers and other materials salvaged from the Santa María. Because the Niña could not accommodate all of the sailors, thirty-nine men would be left at La Navidad with instructions to exchange and trade for gold.

When word reached Columbus that the Pinta had been spotted (Martín Pinzon had left with the Pinta 36 days earlier to seek his own fortune), preparations were begun for their return to Spain. Three days later, on December 30th, Columbus and Guacanagarí sealed their friendship with the exchange of gifts. Guacanagarí removed the crown from his head and placed it on Columbus. In return, Columbus dressed Guacanagarí in a fine red cape, high-laced shoes, a necklace of multicolored agates, and a silver ring. Both men, perhaps unwittingly, had chosen the most important symbols of the other’s culture. Columbus’s “coronation” meant far more to Columbus than it would have to a Taino; and the gift of a red cape was perhaps the greatest honor Columbus could have bestowed. Following the exchange, Columbus provided a display of the weapons aboard the Niña, and promised to protect Guacanagarí from his enemies.

When Columbus returned to La Navidad with the Grand Fleet on November 28, 1493, he learned that all of the Christians were dead and that La Navidad had been burned to the ground. Recent evidence of the conflagration has come from the work of archaeologist Kathleen Deagan of the Florida Museum of Natural History. In addition to a handful of objects of European origin and the bones of Old World rats and pigs, research at the archaeological site believed to be La Navidad has uncovered mineral-encrusted potsherds that could only have formed at temperatures greater than 1400° C. Thus, the inferno was so intense, the wattle-and-daub structures must have acted like kilns.

History records that the Spaniards were killed because they abused the local people. If such local violations were the cause, then the local leader, Guacanagarí, should have ordered the killing. Yet, Columbus did not blame Guacanagarí. Instead, Caonabó, the primary cacique for this region and the ruler to whom Guacanagarí owed fealty, was blamed. Would another leader have acted differently? Had he allowed Guacanagarí to harbor a well-armed garrison of Europeans his own survival would have been threatened. Columbus’s son Ferdinand wrote that when Caonabó was captured he admitted to killing twenty of the men at La Navidad. Caonabó was sent to Spain to stand trial, and Columbus moved his base of operations 70 miles to the east where he established the colony of La Isabela.

Always the restless explorer, Columbus soon tired of administration and set out to explore the coast of Cuba. On April 25, 1494, he stopped to visit Guacanagarí. The cacique, upon learning of the Admiral’s arrival, fled in fear of his wrath. His fear dated back to Columbus’s return to La Navidad in 1493. While passing the Leeward Islands and then Puerto Rico Columbus had taken on board a number of Indians called “Caribees.” Guacanagarí had helped these captives to escape. To make matters worse, he had kept one of the freed captives as a wife. Columbus was in too great of a rush to wait for his old friend’s return, but appears to have harbored no animosity.

By March of 1495 Columbus and Guacanagarí found that they again needed each other. The Tainos in the central part of the island were in open rebellion. With his brother Bartolomé, two hundred Christians, 20 horses and 20 dogs Columbus marched into the interior to quiet the rebellion. Guacanagarí and his men marched at the Admiral’s side. Revenge was his reason. He was hated by the other caciques for cooperating with the Spanish. They flaunted this hatred by killing one of his wives and stealing another — capital offenses in Taino society.

That campaign in the Vega Real contains the last words written about Guacanagarí. He was a man who had history thrust upon him. A man who saw the opportunity to improve his station in life and did so. Where others viewed the Spaniards as their enemy, he came forward and embraced Columbus as a friend.

Published in VISTA, July 7, 1991

Between 86 to 89 men accompanied Christopher Columbus on his first voyage. There were 20 on the Niña, 26 on the Pinta, and 41 on the Santa María. After the Santa María sank, 39 men were left to establish a fort, La Navidad (the Santa María sank on Christmas eve), in the village of the Taino cacique Guancanagari.

What follows is a listing of crew members by vessel along with a separate list for those who were left at La Navidad. The Pinta was away when the colonists were chosen so her crew remained the same shipwreck, with some remaining in Hispaniola and others returning on Niña.

Sailors of the day were often known only by their given name and the city whence they came; for example, “Alonso de Palos” aboard the Pinta, the form in which many of the names appear. The list is probably not complete and contains both duplications and omissions. Alternate spellings are given in parentheses, and it is possible that the same person is listed more than once with a slightly altered spelling.

The list was compiled by Alice B. Gould (“Nueva lista documentada de los tripulantes de Colón en 1492”, Boletín de la Real Academia de la Historia (vols. 85-88, 90, 92, 110, 111. Madrid, 1922-1938) and J. B. Thatcher (Christopher Columbus: His Life, His Work, His Remains, 3 vols. New York, 1903-194). The present list is modified from Robert H. Fuson, The Log of Christopher Columbus (Camden, Maine, 1987).

PINTA

García Alonso

Pedro de Arcos, from Palos

Bernal, servant

Diego Bermúdez

Juan Bermúdez

Antón (Antonio) Calabrés

Maestre Diego, surgeon

Christóbal García Xalmiento (Jalmiento, Sarmiento), pilot

Bartolomé García

Francisco García Gallego

Francisco García Vallejo

García Hernández (Fernández), steward

Juan de Jérez (Xéres), from Palos

Fernando Méndes (Méndez, Mendel)

Francisco Méndes (Méndez, Mendel)

Alonso de Palos

Alvaro Pérez

Gil Pérez

Juan Pérez Viscaino

Martín Alonso Pinzón, Captain

Francisco Martín Pinzón, Master

Diego Martín Pinzón

Juan Quadrado

Christóbal Quintero, Owner

Juan Quintero

Gómez Rascón

Juan Reynal

Juan Rodríquez Bermejo

Pedro Tegero (Tejero, Terreros?)

Rodrigo de Triana

Juan Veçano (Vezano)

Juan Verde de Triana

NIÑA

García Alonso

Maestre Alonso, physician

Juan Arias, cabin boy

Juan Arraes

Pero (Pedro) Arraes

Bartolomé García, boatswain

Alonso Gutiérrez Querido

Andrés de Huelva

Diego Lorenzo

Rodrigo Monge (Monte)

Alonso de Morales, carpenter

Francisco Niño

Juan Niño, Owner and Master

Pero (Pedro) Alonso (Peralonso) Niño, pilot

Juan Ortíz

Gutiérrez Pérez

Vicente Yáñez Pinzón, Captain

Bartolomé Roldán, apprentice pilot

Juan Romero

Sanco Ruíz (de Gama?)

Pero (Pedro) Sánches (Sánchez)

Miguel de Soria, servant

Pedro de Soria

Fernando de Triana

SANTA MARIA

Pedro de Acevedo

Master Alonso, physician

Diego Bermúdez

Pedro del Bilbao

Bartolomé Biues (Vives?)

Cristóbal Caro, goldsmith

Chachú, boatswain

Alonso Chocero

Alonso Clavijo (criminal granted amnesty)

Cristóbal Colón, Captain-General

Juan de la Cosa, Owner and Master

Antonio de Cuellar, carpenter

Master Diego, boatswain

Rodrigo de Escobar

Ruíz (Ruy) Fernández

Gonzalo Franco

Rodrigo Gallego, servant

Ruíz (Ruy) García

Francisco de Huelva

Juan, servant

Maestre Juan

Juan de Jérez

Rodrigo de Jérez (Xérez)

Diego Leál

Pedro de Lepe

Domingo de Lequeitio

Lope (López), joiner

Juan Martínes (Martínez) de Açoque

Juan Medina, tailor

Juan de Moguer (criminal granted amnesty)

Diego Pérez, painter

Juan de la Plaça (Plaza)

Jacomél Rico

Juan Ruíz de la Peña

Sanco Ruíz (de Gama?), pilot

Diego de Salcedo, servant of Columbus

Juan Sánchez, physician

Rodrigo (Pedro?) Sánchez, Comptroller of fleet

Pedro de Terreros (Tejero), steward

Pedro de Terreros, cabin boy

Bartolomé de Torres (criminal granted amnesty)

Luis de Torres, interpreter

Martín Urtubía

Pedro de Villa

Domingo Vizcaino

Pedro Yzquierdo (criminal granted amnesty)

Men left at La Navidad

Cristóbal del Alamo

Diego de Arana, Master-at-arms of fleet, Captain at La Navidad

Francisco de Aranda

Gabriél Baraona

Juan del Barco

Domingo de Bermeo, cooper

Pedro Cabacho

Diego de Capilla

Castillo, silversmith

Juan de Cueva

Rodrigo de Escobedo, Secretary of fleet, Lieutenant at La Navidad

Francisco Fernández

Gonzalo Fernández (from Segovia)

Gonzalo Fernández de Segovia (from Leon)

Pedro de Foronda

Diego García

Francisco de Godoy

Jorge González

Pedro Gutiérrez, representative of royal household, Lieutenant

Francisco de Henao

Guillermo Ires (William Harris or William Penrise, from Ireland)

Antonio de Jaén

Francisco Jiménez

Martín de Lograsan

Alvar Pérez Osorio

Juan Patiño

Diego de Mambles

Sebastián de Mayorga

Alonso Vélez de Mendoza

Diego de Mendoza

Juan de Mendoza

Diego de Montalban

Juan Morcillo

Hernando de Porcuna

Tristán se San Jorge

Pedro de Talavera

Bernandino de Tapia

Diego de Tordoya

Diego de Torpa

Juan de Urniga

Francisco de Vergara

Juan de Villar

BORN

BORN

Between August 25th and October 31st, 1435 to 1460. 1451 is the most frequently given date.

BIRTHPLACE

Columbus said Genoa, Italy. Other candidates — Chios, which is now Greek but was a Genoese colony where Columbus is a common surname. Also, Majorca (Spanish Balearic Islands), Galicia, and other places in Spain.

MARITAL STATUS

Married Doña Felipa Perestrello e Moniz, 1479

CHILDREN

Diego, born to Doña Felipa, 1480, Madeira Islands. Fernando, born to Beatriz, 1488.

WIDOWER

Doña Felipa died between 1481 and 1485.

SIGNIFICANT OTHER

Beatriz Enríquez de Arana, after 1485.

DIED

May 20, 1506, Valladolid, Spain, age-related.

BURIED

Leading candidates: Sevilla, Spain; Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic; or Havana, Cuba.

IMPORTANT RELATIVES

Bartolemé Colón (older or younger, brother or uncle).

PHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS

Blonde hair (white after age 30), blue eyes, exceptionally keen sense of smell, excellent eyesight, perfect hearing. Perfect physical condition in 1492. Moderate in drink, food, and dress; never swore.

RELIGION

Catholic. Jewish background on one side of his family. Left son Diego at Franciscan friary, la Rabida, in 1481, retrieved him in 1491.

EXPERIENCE

Went to sea at age 14. May have been involved in naval engagement between Franco-Portuguese and Genoese Fleets in 1476. Made at least one voyage to England, possibly one to Iceland. Made four voyages to the New World: 1) September 8, 1492 to March 3, 1493; 2) October 7-10, 1493 to June 11, 1496; 3) May 30, 1498 to August 31, 1498 (Santo Domingo, see below for return to Spain); and 4) May 9, 1502 to November 7, 1504 [marooned in Jamaica — June 25, 1503 to March 7, 1504].

CRIMINAL RECORD

Arrested in Santo Domingo August 23, 1500. Sent to Spain in chains in October 1500. Released December 12, 1500 and summoned to court.

Originally Published in Vista Magazine.