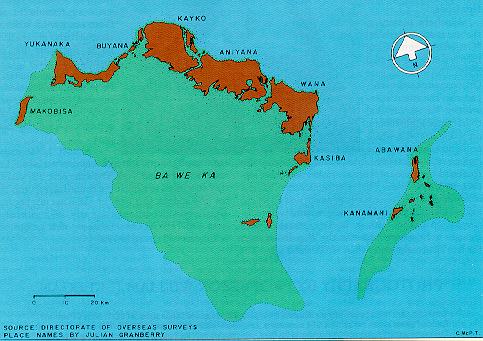

Baweka, translated from the Taino language as “Large Northern Basin,” was the name for the Caicos Bank at the time of Columbus. From Abawana (Grand Turk) to Makobisa (West Caicos) the islands supported a thriving native population on the eve of European conquest.

Nestled between the Bahama Islands to the north and Hispaniola to the south, the Turks and Caicos occupied a strategic position in the northern West Indies. A position that resulted in a unique culture history.

Once called Arawaks for the family in which their language is classified, Native West Indian societies are today called Taino on the strength of cultural similarities. Geographical distinctions are made between Western (central Cuba and Jamaica), Eastern (Virgin Islands), Classic (eastern Cuba, Hispaniola, and Puerto Rico), and Lucayan (Bahamas) Tainos; and finer distinctions within these regions are now being defined. For example, at least three mutually unintelligible languages were spoken in Hispaniola at contact. Even after decades of research, the most difficult question for archaeologists to answer is: Who where the Tainos?

Knowledge about the Taino occupants of the Turks and Caicos comes largely from the work of three archaeologists. The first was Theodoor DeBooy who visited all of the islands except West Caicos in the latter half of 1912 under sponsorship of the Heye Foundation and the Museum of the American Indian in New York City. DeBooy and collectors who came before him obtained exquisite examples of Taino art. But because these were rare in comparison to finds in the Greater Antilles, interest in the islands soon waned.

Seventy-five years would pass before the next archaeologist, Dr. Shaun Sullivan, would come to the islands. Sullivan devoted two years to surveys and excavations in the Caicos Islands in an effort to track the Taino colonization of the Bahama archipelago (composed of the Turks and Caicos and Commonwealth of the Bahamas). He rediscovered forty Taino sites, all but five on Middle Caicos, and brought to light the unique characteristics of these sites. He also introduced Brian Riggs and myself to the Turks and Caicos.

After working with Sullivan on Middle Caicos in 1978, I spent several years studying shell-tool making at the site on Pine Cay. After excavating site MC-12 on Middle Caicos with Sullivan, Glen Freimuth, and Brian Riggs in 1982, I initiated a series of archaeological surveys in the southern and central Bahamas to track the movement of the Tainos as well as the first voyage of Christopher Columbus.

It was Columbus who brought me back in 1989 to a conference at which Robert Power and Josiah Marvel presented their case for Grand Turk as the first landfall of Columbus. During their conference I found two Taino sites on Grand Turk on either side of the Governor’s estate. Bob Power died of cancer before the Quincentenary, but he went to his grave believing that the last piece of the puzzle — Indians living on Grand Turk — had been found.

Actually, what we have found since is, to me, far more interesting than Columbus’ first landfall. With the help of Mrs. Grethe Seim and Brian Riggs through the Turks and Caicos National Museum, and with funding from the National Geographic Society, we have begun to write the story that DeBooy and Sullivan first outlined.

This article was originally published under the title “History Begins on Grand Turk” in Times of the Islands: The International Magazine of the Turks and Caicos. It was published in the Summer 1995 issue and is reprinted here with their kind permission.

Times of the Islands, ISSN 1017-6853, is published four times per year by Times Publications Ltd., P.O. Box 234, Providenciales, Turks and Caicos Islands, BWI. E-mail: timespub@caribsurf.com