Calcium is abundant, which means that people in the past figured out some great ways to use it as tools, decoration, and, of course, pottery. In nature, we typically find calcium bound in carbonate minerals, which also contain carbon and oxygen. The limestone bedrock of Florida and the Bahamas is carbonate, and so are coral, the shells of oysters, conch, and other shellfish.

In the past, crushed shells, limestone, and bone have been used as tempering materials for pottery, especially in places where there isn’t much other “hard stuff” around. In the Southeastern US, they were used specifically to make cooking pots, because the clay and the calcium minerals expand the same amount when heated. This is important to avoid cracks in your cookware.

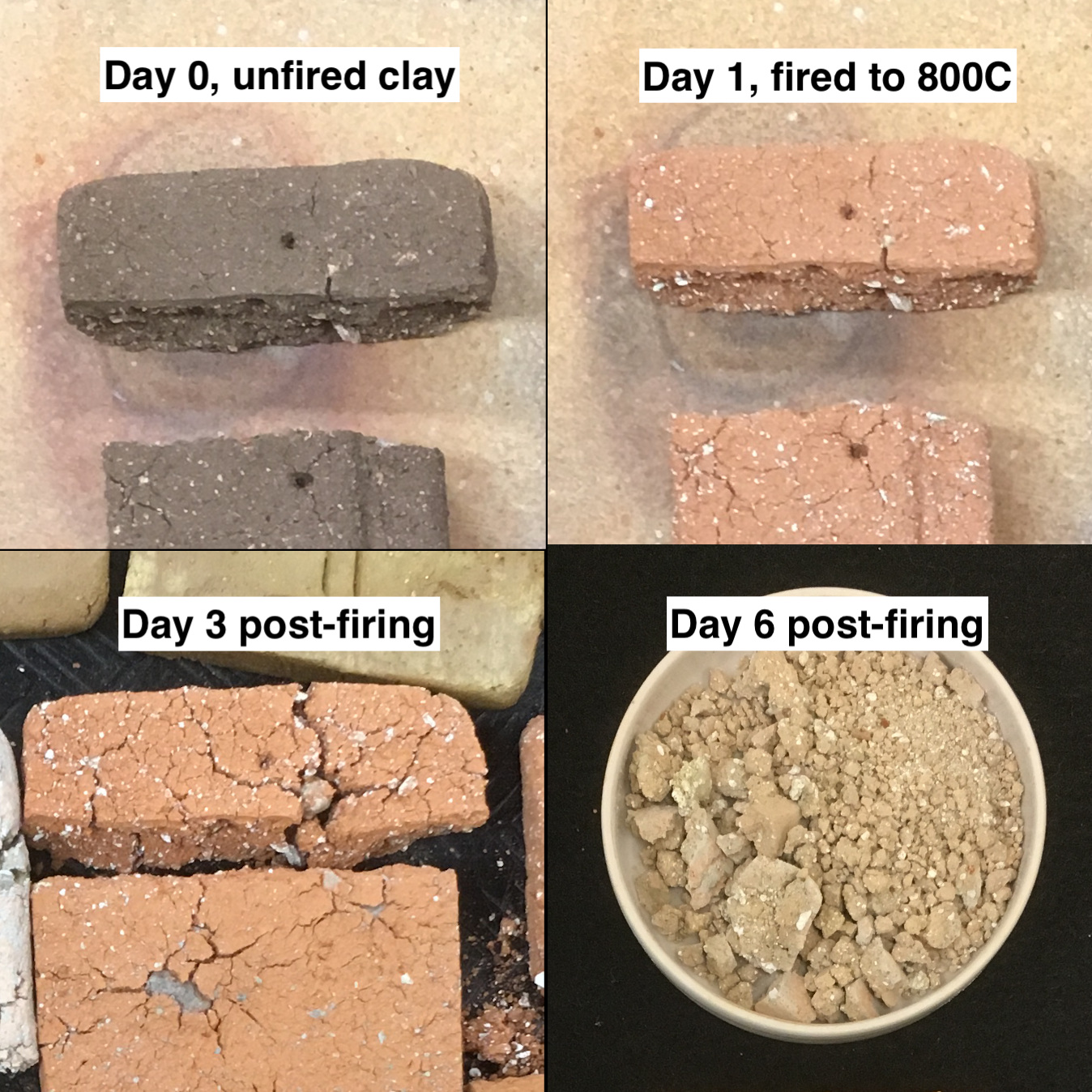

But, and it’s a big but, calcium minerals are tricky to work with. This is because above around 700°C, the calcium carbonate (CaCO3) converts into quicklime (CaO) and carbon dioxide (CO2). Quicklime is softer than calcium carbonate, so an overfired pot will feel light and fragile. Here’s an example showing how shell temper inclusions change with increasing temperature, with a major difference between 600°C and 700°C. Notice how the shell particles are more visible in the top two briquettes, both whiter and larger. Aside from temperature, the briquettes are identical. We usually think that hotter is better to make a stronger pot, but in this case it’s the opposite.

Most devastating, quicklime readily combines with water, including the water suspended in our humid Florida air. Over time, that means that the quicklime particles begin to expand, taking on water. As they grow, they become more fragile and cracks begin to form. In the most severe cases, you’re left with a pile of dust. Here’s a clay that naturally contained a lot of calcium carbonate, but didn’t have tempering added:

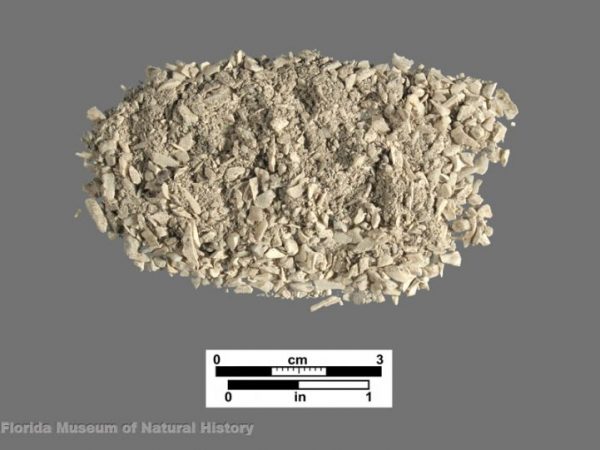

In bad news for archaeologists, even low-fired carbonate tempered pottery doesn’t always preserve well. This is because the calcium (which is basic), gets eroded over time from acidic conditions in the ground or water. Notice in most of these limestone tempered sherds how there are holes where the temper used to be:

Despite these limitations, potters 1000 years ago figured out how to use shell and limestone to their advantage, engineering pots that would be strong for cooking or other activities, and showing deft control over very tricky firing conditions, without the benefits of modern thermometers. Truly remarkable.

Here’s our recent foray into shell-tempered pottery making: Clay Chronicles VI