Our lab holds one of the most complete type collections of pottery from Florida. On a regular basis, students and other researchers come by with a pottery sherd they can’t identify, and go through our drawers to find a match with a named type. Some of our sherds could even be classified as holotypes, the actual specimens that were used to define the types more than 50 years ago.

Our lab holds one of the most complete type collections of pottery from Florida. On a regular basis, students and other researchers come by with a pottery sherd they can’t identify, and go through our drawers to find a match with a named type. Some of our sherds could even be classified as holotypes, the actual specimens that were used to define the types more than 50 years ago.

Who decided what was a “type” and what to call it?

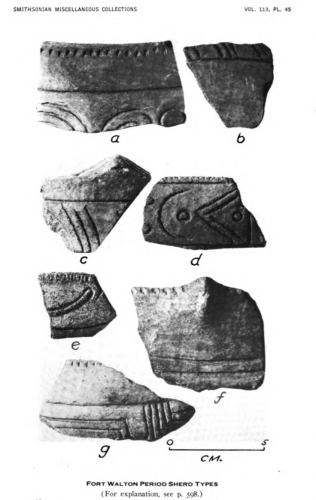

The majority of the Florida types were first described in the late 1940s and early 1950s. We owe most of the types to Gordon Willey, with James Griffin, John Goggin, and others developing some series. Here’s one example of a Point Washington Incised sherd, photographed in Gordon Willey’s Archeology of the Florida Gulf Coast in 1949 where he first defined this type, and again by us in 2020 for our digital type collection.

In Florida and elsewhere in the Southeast, it has been standard practice to establish a type name based on a relevant geographic feature or site. That’s how we ended up with type names like Opalocka Incised, and Gainesville Linear Punctated. While they may be named for a particular place, that doesn’t mean the type is only found at one site. In fact, naming a type based on sherds from a single site runs counter to the initial goals and directives of pottery naming.

In 1938, James Ford and James Griffin, key figures in Southeastern archaeology strongly counseled, “If these type names are to be useful in untangling the prehistory of the southeast, they must have more than local significance…The specific combination of features must be repeated at different sites to be certain that we are dealing with a pottery style that had a significant part in the ceramic history of the area.” Ford and Griffin’s language emphasized that types are first and foremost comparative tools, and are subject to debate.

At the same time, it was argued that type names should not be taken from ethnic, linguistic, or cultural labels, in order to avoid conflating artifacts and cultures. Florida has not been good at sticking to this. Geographic names have also become culture names: St. Johns, Weeden Island, Safety Harbor, etc. As you can learn from our recent study of St. Johns pottery, this can be a problem because it leads to assumptions about place, time, and pottery.

Our type collection is a record of the history of archaeology in Florida, as folks like Gordon Willey were testing out categories and names to see what would stick. It still includes some examples of truly provisional types, like “Unique Incised,” which we now identify as a variant of Matecumbe Incised. While I imagine that most archaeologists have, somewhere, a shelf of our unknown artifacts awaiting identification, applying a permanent label that’s equivalent to “we don’t know what to call this” is something we probably would not do today.

There’s lots more to say about pottery types and their names. For an overview, check out Lindsay and Amy’s article in the SAA Archaeological Record. To explore the more than 100 pottery types in Florida, visit our online database.