Let’s look a little closer at sharks parts, habits, and biology:

Neutral buoyancy means being as heavy or dense as the fluid around you so that you don’t sink down or float up.

Sharks have several adaptations that can help them be neutrally buoyant. Sharks lack true bone but instead have cartilaginous skeletons that are much lighter. Sharks also have large livers full of low-density oils, which provide some buoyancy.

While sharks lack a swim bladder that many bony fish have, some species of shark, like the sand tiger (Carcharias taurus), can actually gulp air into their stomach, which can provide additional buoyancy.

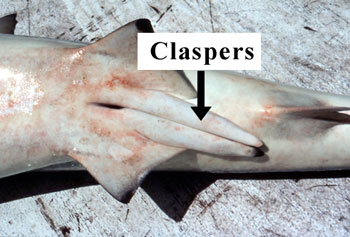

Male sharks have paired intromittent organs called claspers. Claspers are modifications of the pelvic fins and are located on the inner margin of the pelvic fins. Females do not have claspers.

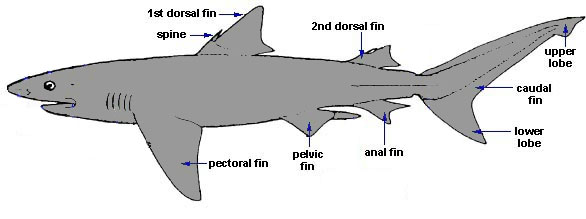

Sharks have five different types of fins: pectoral, pelvic, dorsal, anal, and caudal. These fins are rigid and supported by cartilaginous rods.

The paired pectoral fins are located ventrally near the anterior (front) end of the shark. They are used primarily for lift as the shark swims.

The paired pelvic fins located behind the pectoral fins are used for stabilization while the shark swims.

The dorsal fin is the one that commonly appears skimming along the water’s surface. Sharks may have one or two dorsal fins that act to stabilize the shark during swimming. The second dorsal fin is usually smaller than the first dorsal fin and is located posteriorly (toward the tail) to the first larger dorsal.

Stability is the main function of the anal fin for sharks that have one, other sharks may lack this fin. It is located on the ventral (bottom) side between the pelvic and caudal fins.

The caudal fin is also called the tail fin. The upper half and the lower half of the shark’ tail are not equal in size with the upper portion usually the larger. This is especially pronounced in the thresher shark that has an upper tail lobe longer than the shark’s body. This fin is responsible for propelling the shark through the water as it swims.

Sharks exhibit a great diversity in reproductive modes.

There are oviparous (egg-laying) species and viviparous (live-bearing) species. Oviparous species lay eggs that develop and hatch outside the mother’s body with no parental care after the eggs are laid. The embryos are nourished by a yolk-sac inside the egg capsule.

Viviparous species can be separated into two categories: placental (having a placenta, or true connection between maternal and embryonic tissue), or aplacental (lacking a placenta). Among the aplacental species, there are those whose embryos rely primarily on a yolk-sac for nutrition during gestation and those that consume yolk-filled, unfertilized egg capsules (oophagy).

There is even one species, the sandtiger (Carcharias taurus), in which the two largest embryos that were fertilized first, consume the other embryos of the litter (adelphophagy). It has also been suggested that the young of some viviparous species may be nourished by uterine secretions during some part of gestation, but this has not been conclusively documented. There is no parental care after birth among viviparous sharks.

*Aplacental viviparity can also be described as ovoviviparity, although that term is rarely used today.

This name is given to the egg cases of many sharks and skates. This tough, protective purse-shaped egg case contains one fertilized egg. A young shark or skate later emerges from the mermaid’s purse. Shark species that utilize this mode of reproduction include the swell shark, dogfish, and angel sharks.

All sharks have internal fertilization. Mating has been observed in relatively few species of sharks, but both hormonal and behavioral cues are likely involved. The female is typically passive as the male bites and grasps her with his teeth to hold on during copulation. Then, the male inserts a clasper into the female’s cloaca and releases sperm. Depending on species, sperm may or may not be stored in the female prior to fertilization of the oocyte, or ovum.

All sharks have internal fertilization. Mating has been observed in relatively few species of sharks, but both hormonal and behavioral cues are likely involved. The female is typically passive as the male bites and grasps her with his teeth to hold on during copulation. Then, the male inserts a clasper into the female’s cloaca and releases sperm. Depending on species, sperm may or may not be stored in the female prior to fertilization of the oocyte, or ovum.

During ovulation, the female releases oocytes from the ovary. Then, these oocytes are fertilized by sperm, and the fertilized ova are encapsulated in an egg case in a specialized organ called the nidamental or shell gland. In all oviparous species and most viviparous species, a yolk sac is packaged in the egg case along with the ovum.

Development of the embryo then proceeds according to the mode of reproduction and embryonic nutrition of the particular species (see question above). In oviparous species, eggs are laid. In viviparous species, gestation takes place in the uterus. Sharks are hatched or born as juveniles, or smaller versions of the adult. There is no larval stage.

A baby shark is referred to as a pup.

Most sharks live only in the marine environment in full-strength saltwater. Some coastal shark species can survive in brackish estuaries with mixed fresh- and saltwater. Many juvenile sharks use these brackish areas as nursery grounds.

There are only a couple shark species that are capable of surviving in freshwater for any length of time, and these have special physiological adaptations that allow this. These species are the bull shark (Carcharhinus leucas) and the speartooth shark (Glyphis sp.).

Bull sharks have been captured ~2,100 miles (3,480 km) up the Amazon River, and ~1,700 miles (2,800 km) up the Mississippi River. Bull sharks have also been documented to traverse ~108 miles (175 km) of rapids in the Rio San Juan leading up to Lake Nicaragua from the Caribbean Sea.

The speartooth shark has been captured over ~60 miles (100 km) up the Adelaide River in Australia. Though these sharks are capable of surviving in freshwater, there are no populations living in completely landlocked freshwater lakes. They always have a route that will connect them to the ocean.

![]() Sharks have a tongue referred to as a basihyal. The basihyal is a small, thick piece of cartilage located on the floor of the mouth of sharks and other fishes.

Sharks have a tongue referred to as a basihyal. The basihyal is a small, thick piece of cartilage located on the floor of the mouth of sharks and other fishes.

It appears to be useless for most sharks with the exception of the cookiecutter shark. The cookiecutter shark uses the basihyal to rip chunks of flesh out of their prey.

Taste is sensed by taste buds located on the papillae lining the mouth and throat of the shark. The taste receptors help the shark decide if the prey item is suitable or not prior to ingesting the item.

Most sharks, like most fishes, are cold blooded, or ectothermic. Their body temperatures match the temperature of the water around them.

Most sharks, like most fishes, are cold blooded, or ectothermic. Their body temperatures match the temperature of the water around them.

There are however 5 species of sharks that have some warm blooded, or endothermic capabilities. The family lamnidae, known as mackerel sharks, includes the white (Carcharodon carcharias), shortfin mako (Isurus oxyrinchus), longfin mako (Isurus paucus), porbeagle (Lamna nasus), and salmon (Lamna ditropis). This family has the unique ability to elevate their internal body temperatures above that of their surrounding environment by the use of a highly-developed network of blood vessels that retain the heat produced by their muscles.

The white shark is able to maintain its stomach temperature as much as 57ºF (14ºC) warmer than the ambient water temperature at swimming depth i.e. a white shark swimming in waters measuring 57ºF (14ºC) can sustain a stomach temperature of 82ºF (28ºC).

The salmon shark is possibly the most warm blooded shark, and maintains its body temperature at around 77ºF (25ºC). This is 35ºF (21ºC) warmer than the sub-arctic waters where it lives.

The nictitating membrane is a thin, tough membrane or inner eyelid in the eye of many species of sharks. This membrane covers the eye to protect it from damage, especially just prior to a feeding event where the prey may inflict damage while trying to protect itself.

Sharks have many keen senses that are mostly geared towards helping them locate prey. Depending on the species or the environment certain senses are more or less important to them for locating their targeted prey, which is most often fish. Sharks use the senses of smell (chemoreception), vision, hearing, the lateral line system, and electroreception (ampullae of Lorenzini) for capturing prey.

Sharks have many keen senses that are mostly geared towards helping them locate prey. Depending on the species or the environment certain senses are more or less important to them for locating their targeted prey, which is most often fish. Sharks use the senses of smell (chemoreception), vision, hearing, the lateral line system, and electroreception (ampullae of Lorenzini) for capturing prey.

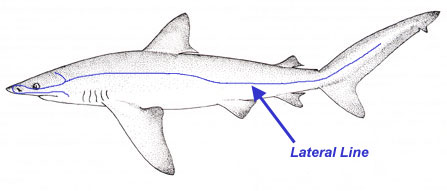

The lateral line system, which all fishes possess, allows them to detect waves of pressure or mechanical disturbances in the water.

The ampullae of Lorenzini are receptors that can detect weak electric fields. This sense is unique to sharks and their relatives. Sharks primarily use this sense to locate cryptic prey which can not be detected by their other senses, such as stingrays buried in sand. The stingray, like all living animals, emit weak electric fields produced by muscular contractions in the body. Sharks have the extra predatory advantage of being able to detect those fields at close range. More information on electric organs of elasmobranchs and other fish adaptations.

Hunting habits of three species are summarized below: the white (Carcharodon carcharias), tiger (Galeocerdo cuvier), and bull (Carcharhinus leucas) sharks. These species are also responsible for the majority of attacks on humans.

The white shark, when targeting seals in coastal areas, is thought to be a primarily visual ambush predator. It cruises on or near the ocean bottom looking up to the surface for basking or swimming seals. When a seal is spotted it will make a high speed rush and attempt to mortally wound it in the first strike. It is believed that most white shark bites on surfers are the result of the shark mistaking the surfboard for a seal. In most cases, once the shark gets a mouthful of fiberglass or neoprene instead of a fatty seal, it will tend to leave the scene. This initial strike can however leave a victim with serious wounds.

Tiger sharks are usually nomadic in their movements, and therefore use their “long-range” senses, like smell and hearing, for helping to key in on prey. They can detect the scent of dead fish, birds, or turtles from very long distances, and follow the odor corridor to its source. Once close enough, vision becomes the more dominant sense leading up to the consumption of the prey. Of course, chance visual encounters with live prey often occur as well.

are usually nomadic in their movements, and therefore use their “long-range” senses, like smell and hearing, for helping to key in on prey. They can detect the scent of dead fish, birds, or turtles from very long distances, and follow the odor corridor to its source. Once close enough, vision becomes the more dominant sense leading up to the consumption of the prey. Of course, chance visual encounters with live prey often occur as well.

Bull sharks tend to occur in shallow coastal waters where visibility is often poor. They have smaller eyes than other closely-related sharks, and it is therefore believed that bull sharks do not rely on vision as much as some of their other senses. When relying more on the sense of hearing, smell, or their lateral line, they can more easily mistake human activity in the water as that of their prey which is mostly comprised of schooling fishes.

Apex predators are at the top of the food chain and have few or no natural predators. Sharks fit this category, feeding on fish, seals, and large invertebrates and having few predators.

Apex predators keep populations of prey animals in check, and are thereby important in maintaining the ecological balance of its environment.

The lateral line is comprised of a series of tubes located just below the surface of the skin, running lengthwise on both sides of the shark’s body, from the head all the way to the tail. The pores are open to the outside where water flows through, into the tubes below the skin. These tubes are lined with hair-like projections that are connected to sensory cells.

When moving water, sound, vibration, and pressure changes stimulates these sensory cells, the shark is alerted to potential prey in nearby waters.