Carcharhinus plumbeus

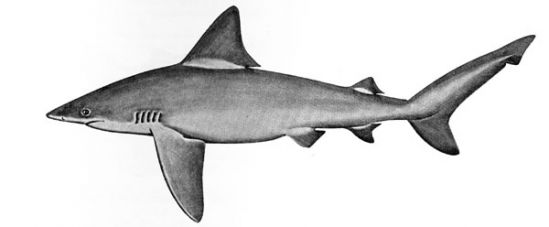

This brownish-gray shark has a recognizably large and triangular dorsal fin and somewhat long pectoral fins. It averages 6 feet long and about 110-150 lbs. True to its name, this shark prefers the sandy bottoms of coastal areas, and is known for seasonal migration like many other requiem sharks. Because it has a high fin-to-body weight ratio, the sandbar sharks have been targeted by commercial and sports fishers, but it has a long growth and reproduction cycle so it is earning selected protected status in many areas.

Order – Carcharhiniformes

Family – Carcharhinidae

Genus – Carcharhinus

Species – plumbeus

Common Names

Common names in the English language includes brown shark, queriman shark, sandbar shark, shark, and thickskin shark. Other names are arenero (Spanish), barriga-dágua (Portuguese), büyükcamgöz baligi (Turkish), cação-baleeiro (Portuguese), carcharias (Greek), cazón (Spanish), jarjur (Arabic), karcharynos tefros (Greek), kelb gris (Arabic), kelb griz (Maltese), köpek baligi (Turkish), manô (Hawaiian), marracho de milberto (Portuguese), mejirozame (Japanese), pas sivonja (Serbian), peshkagen i hirte (Albanian), qarsh rmâdy (Arabic), requin gris (French), sandbankhaai (Afrikaans), skylópsaro (Greek), squalo grigio (Italian), staktocarcharias (Greek), tiburón aletón (Spanish), tubarão-cinzento (Portuguese), zandbankhaai (Dutch), and zarlacz brunatny atlantycki (Polish).

Importance to Humans

The sandbar shark plays an important role in the commercial shark fishery along the eastern United States. In fact, because of its numbers, moderate size, palatable meat, and high fin-to-carcass ratio, it is the primary targeted species in this area. It is also harvested in the eastern North Atlantic as well as the South China Sea for its fins, flesh, skin and liver. In addition to the significant impact the sandbar shark has on the commercial fishery, it is valuable to recreational fishermen as a game fish.

Danger to Humans

Due to its preference for smaller prey and its tendency to avoid beaches and the surface, the sandbar shark poses little threat to humans. Although it has been rarely associated with attacks on humans, its size makes it potentially dangerous.

Conservation

The sandbar shark exhibits a reproductive strategy that includes small litter size, slow growth rate, and a relatively long gestation period. Consequently this shark is vulnerable to over-exploitation by fishing. Increased recreational fishing and a heightened demand for shark fins, as well as shark meat, in the 1980’s had a profound adverse effect on the numbers of sandbar sharks in the southwestern Atlantic. It has been proposed that the population of sandbar sharks in this area dropped by two-thirds between the 1970’s and early 1990’s. However, there has been a slight rise in population numbers in recent years directly as a result of the implementation of fishery regulations. In addition, it is believed that there has been a decrease in predation of juvenile sandbar sharks in nursery grounds by larger sharks, based on declining populations of large predatory sharks.

> Check the status of the sandbar shark at the IUCN website.

The IUCN is a global union of states, governmental agencies, and non-governmental organizations in a partnership that assesses the conservation status of species.

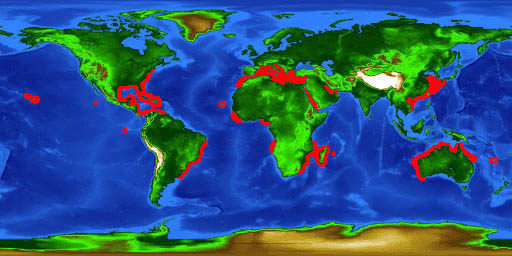

Geographical Distribution

The sandbar shark is a coastal-pelagic species that inhabits temperate and tropical waters. It is the most abundant species of large shark in the Western Atlantic. It has a global distribution, being found in the Western and Eastern Atlantic, including the Mediterranean. In the Indo-Pacific, it ranges from the Persian Gulf, Red Sea and South and East Africa to the Hawaiian Islands. It also inhabits the Revillagigedo and Galapagos islands in the Eastern Pacific.

Habitat

C. plumbeus is essentially a bottom-dwelling, shallow coastal water species that is seldom seen at the water’s surface. It tends to prefer waters on continental shelves, oceanic banks, and island terraces but is also commonly found in harbors, estuaries, at the mouths of bays and rivers, and shallow turbid water. Despite this, plumbeus is exclusively a marine species and does not venture into freshwater. It is believed that the sandbar shark favors a smooth substrate and will avoid coral reefs and other rough-bottom areas. It spends most of the time in water from 20-65 m (60-200 ft) deep but undoubtedly moves into deeper water to undergo migration.

As with many sharks of its genus, the sandbar shark undergoes seasonal migrations. These movements are influenced mainly by temperature although it is believed that ocean currents also play a significant role. In the western North Atlantic, adult sandbars move as far north as Cape Cod during the warmer summer months and return to the south at the onset of the cooler weather. Males migrate earlier and in deeper water than females. Male sandbar sharks demonstrate congregated migrations and often travel in large schools while females exhibit solitary migrations.

It is believed that populations of this species along the southeastern coast of Africa also take part in seasonal migrations. Off the Hawaiian Islands, however, sandbar sharks are thought to be annual residents. Due to the vast distances between known populations of sandbar sharks around the world, it is highly probable that these animals are capable of long, pelagic migrations as well. However, these long-range movements are most likely a result of accidental or irregular “rides” of prevailing oceanic currents rather than regular migrations associated with seasonal temperature.

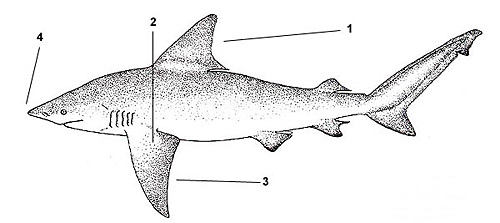

Distinguishing Characteristics

1. First dorsal fin is large and triangular

2. First dorsal fin originates over or slightly before the pectoral fin insertion

3. Pectoral fins are large and broad

4. Snout shorter than width of mouth

Biology

Distinctive Features

The sandbar shark’s most distinguishing characteristic is its taller than average first dorsal fin, which originates above or slightly anterior to the pectoral axis. It has a bluntly rounded snout that is shorter than the width of the mouth. An interdorsal ridge is present between dorsal fins. Its widely spaced dermal denticles have no definite teeth and don’t overlap as is with most sharks of the family Carcharhinidae.

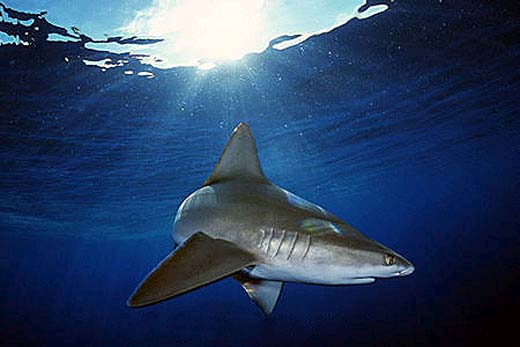

Coloration

This shark is bluish to brownish gray dorsally, and a lighter shade of the same color to white ventrally. Although the tips and outer margins of the fins are sometimes a darker tone, this species has no obvious markings.

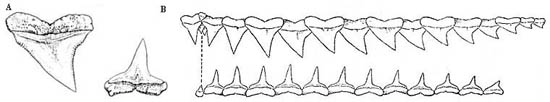

Dentition

The upper teeth of C. plumbeus are broadly triangular, serrated with high cusp. The lower teeth are narrower and more finely serrated. The front teeth are erect and symmetrical but become smaller and increasingly oblique as they move toward the corners of the jaws.

The sandbar shark is an opportunistic bottom-feeder that preys primarily on relatively small fishes, mollusks and crustaceans. Common food items include various bony fishes, eels, skates, rays, dogfish, octopus, squid, bivalves, shrimp and crabs. The sandbar shark feeds throughout the day but becomes more active at night. Due to the high percentage of sharks found with partially full stomachs and their relatively large liver, which contains high percentage of oil and vitamins, it is believed that these sharks have a very successful feeding strategy and receive a more regular supply of food than other carcharhinids.

Reproduction

In the northern hemisphere, mating occurs in the spring or early summer (May-June). Sharks in the southern hemisphere, in correlation with the warmer summer season, mate in late October to January. During this time, a mature male persistently follows a female, occasionally biting the area between her dorsal fins until she turns over allowing him to insert one clasper into the cloaca. This form of courtship behavior, which is present in most carcharhinids, often leaves the female with permanent scaring.

Once fertilization occurs, the gestation period can range from 8-12 months depending upon geographical location. Female sandbar sharks of the western Atlantic generally carry their young for 9 months whereas in southeastern Africa, the gestation period can last as long as 12 months. A female sandbar shark can become gravid every other year, with a resting year occurring after each birthing event. The embryos are nourished via a placental sac, a reproductive strategy known as viviparity. In the western Atlantic, pups are born from June through August while off southeastern Africa, pups are born from December to February. Partuition occurs in shallow water habitats, providing a ‘nursery’ area for young sharks where they are protected from predation by larger sharks (it is well known that adult bull sharks, Carcharhinus leucas, prey heavily on juvenile sandbar sharks).

In the western North Atlantic, the bays and estuaries from Delaware to North Carolina are prime sand bar shark nursery areas. As with gestation period and mating times, litter size also varies by region. In the South China Sea, litters typically number from 6-13, whereas off the Hawaiian Islands, litters average about 7 pups. Regardless of location, litter size is dependent upon the size of the mother, with larger sharks producing larger litters.

Remarkably, both sexes are almost always represented in a 1:1 ratio. Young sandbar sharks resemble their adult parents, although the characteristically large first dorsal fin may not yet be as prominent at this early stage. Juvenile sandbar sharks remain in the shallows until late fall at which time they form schools and move southward and further offshore only to return for the summer months. This movement between shallow coastal waters and warmer, deeper waters may continue for a period of up to five years but should not be confused with adult migrations that involve much greater distances.

Predators

Juvenile sandbar sharks may fall prey to large sharks including the bull shark, however adults have few if any predators.

Parasites

Alebion lobatus is a parasitic copepod found on the sandbar shark.

Taxonomy

The sandbar shark was described by Nardo in 1827 as Squalus plumbeus based on a specimen taken from the Adriatic Sea. In 1841, Muller and Henle assigned Eulamia milberti as the scientific name for the sandbar shark and since then, there have been various names used in its classification. Some of these include Carcharias ceruleus DeKay 1842, Lamna caudata DeKay 1842, Squalus caecchia Nardo 1847, Carcharias japonicus Temminck & Schlegal 1850,Carcharias obtusirostris Moreau 1881, Carcharias stevensi Ogilby 1911, Carcharias latistomus Fang & Wang 1932, and Galeolamna dorsalis Whitley 1944. The species name milberti was used by some scientists until recently, based on the belief that the population of sandbar sharks in the Mediterranean Sea was made up of a distinct species. It is now known that these sharks are identical to those from the western Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. Currently, the valid scientific name is Carcharhinus plumbeus (Nardo, 1827). The genus name Carcharhinus is derived from the Greek “karcharos” = sharpen and “rhinos” = nose. The species name plumbeus is translated from Latin as “of lead”.

Prepared by: Craig Knickle