Cephaloscyllium ventriosum

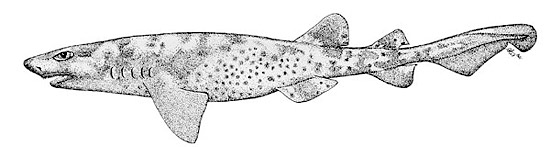

This sluggish, nocturnal shark prefers the rocky, algae-spotted shallows of the eastern Pacific Ocean where it ambushes prey and grows to max size of 110 cm (43 inches) long. It is yellow-brown with dark blotches and white spots, with large mouth and eyes on a blunt snout, and lobed fins set back towards its asymmetrical, notched caudal fin. This shark is not aggressive, and when threatened can curve its body into a U-shape and gulp water into its stomach, swelling to almost twice its size and becoming difficult to bite.

Order: Carcharhiniformes

Family: Scyliorhinidae

Genus: Cephaloscyllium

Species: ventriosum

Common Names

This shark is aptly named the “swell shark” due to its ability to swallow large amounts of water, swelling its body to twice its normal size, when threatened by a potential predator.

- English: swell shark, swellshark, puffer shark

- Dutch: swelhaai

- French: holbiche ventru

- German: schwellhai

- Spanish: gato hinchado, pejegato hinchado, tiburón inflado

- Swedish: blåshaj

Importance to Humans

There are no commercial fisheries for the swell shark. However, it is considered bycatch in the commercial lobster and crab traps, gill nets, and trawls. Incidental catches of this species have the potential to threaten this shark due to its age at maturity and the low number of young it produces.

The swell shark is sometimes fished recreationally, however, it is not consumed by humans due to the poor quality of its flesh.

Public display aquarium facilities often include the swell shark in their tanks as it is able to survive captivity for extended periods of time (Castro, 1983).

Danger to Humans

The swell shark is considered harmless, preferring to avoid contact with humans. It only becomes aggressive when stepped on or harassed and may inflict a superficial wound (Castro, 1983).

Conservation

The swell shark is currently listed as a species of “Least Concern” with the World Conservation Union (IUCN). The IUCN is a global union of states, governmental agencies, and non-governmental organizations in a partnership that assesses the conservation status of species.

> Check the status of the swell shark at the IUCN website.

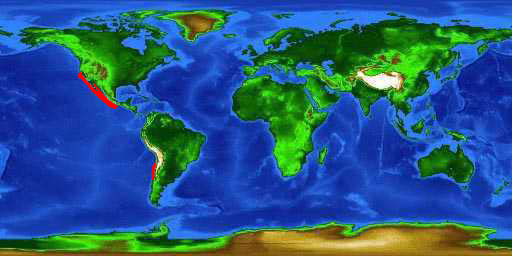

Geographical Distribution

The range of the swell shark is limited to the eastern Pacific Ocean from central California (U.S.) to the Gulf of California and southern Mexico and along the coast of central Chile (Compagno, 1984).

Habitat

This benthic (bottom-dwelling) species resides over continental shelves and upper slopes in temperate and subtropical waters. It can be found to depths of 1,500 feet (457 m), however, it is most common at depths of 16-121 feet (5-37 m). The preferred habitat of the swell shark is rocky, algal covered bottoms. During the day, this small, sluggish shark hides in caves and rocky crevices, camouflaged with its surroundings. As night approaches, the swell shark moves out to adjacent sandy bottoms in search of food. It ambushes prey items or rests quietly on the bottom with its mouth wide open, waiting for an unsuspecting victim. Although the swell shark is primarily a solitary species, it sometimes forms aggregations while resting, with individuals sometimes piled on top of each other (Compagno, 1984).

An interesting characteristic of the swell shark is the ability to inflate its stomach with water. When this shark feels threatened, it bends its body into a U-shaped form and grabs its tail fin with its mouth. It then swallows a large amount of water, swelling its body to twice its normal size. This discourages potential predators, making it difficult for the predator to bite or remove the swell shark from a crevice. When the threat passes, the swell shark makes a dog-like bark when expelling the water. If the swell shark is caught and brought to the surface, it can also swell its body with air in the same manner as it does with water (Castro, 1983).

Biology

Distinctive Features

The swell shark has a stout body and a flat, broad head. The snout is short and the mouth is very large, extending behind the large oval-shaped eyes. This shark’s mouth is proportionally larger than the mouth of the white shark (Carcharodon carcharias) (Castro, 1983).

The eyes have nictitating lower eyelids. The gill slits are quite small. The first dorsal fin is well back on the body, originating behind the origins of the pelvic fins. The claspers are stout and short (Compagno, 1984).

The leopard shark (Triakis semifasciata) has similar coloration and markings to the swell shark but can easily be identified by its first dorsal fin that originates well in front of the pelvic fins (Castro, 1983).

Coloration

The body coloration of the swell shark consists of a mix of yellow and brown with brown blotches and white spots. Younger individuals may appear lighter in color. The underside of the swell shark is also spotted. The fins lack any distinguishing marks (Castro, 1983).

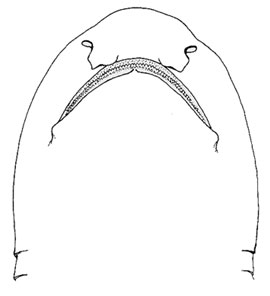

Dentition

The large mouth of the swell shark contains numerous small teeth, usually having three smooth-edged cusps but each may have up to five cusps. The central cusp is extending further than the others. Each jaw contains 55-60 teeth (Castro, 1983).

Size, Age, and Growth

The maximum reported length of the swell shark is 43 inches (110 cm) total length. However, this species is more commonly observed at lengths of approximately 35 inches (90 cm) (Castro, 1983).

Food Habits

As a nocturnal predator, this shark feeds primarily on small reef fishes as well as any prey items that it can easily fit in its mouth (Castro, 1983). Invertebrate prey items include benthic mollusks and crustaceans. This shark feeds by actively sucking in small fishes or by capturing other prey items by remaining motionless on the bottom with its mouth wide open, waiting for prey to wander in or to be swept in by the currents (Ferry, 1997). Swell sharks will sometimes enter lobster traps in search of any easy meal.

Reproduction

The swell shark is oviparous. In this mode of reproduction, a gland secretes a shell that surrounds the egg as it passes through the oviduct. This shell protects the embryo until it hatches. The mother deposits and anchors two egg cases at a time in rocky, algal-covered habitats. Each triangular egg case measures 1-2 inches by 3-5 inches (3-6 cm by 9-13 cm) and has wiry tendrils at each corner that catch on rocks and seaweed (Castro, 1983). The egg cases are rubbery and pale when first released, however they quickly harden and darken with the first few hours. There is a yolk within the egg case that provides nutrients for the developing embryo until the embryo hatches in 9-12 months (Grover, 1974).

This period of time between the egg case being released by the mother and when the pup emerges from the egg case is dependent upon the water temperature. The newborn pup uses enlarged denticles along its back that aid in allowing it to break free from the egg case. Upon emerging, the pup measures 6 inches (15 cm) in length and immediately begins to feed on small benthic mollusks and crustaceans (Grover, 1974).

Predators

Predators include larger sharks and marine mammals including seals. Marine snails often bore holes in the tough protective coating of egg cases, consuming the developing embryo (Cox, 1993).

Taxonomy

Garman (1880) first described the swell shark as Scyllium ventriosum. However, this name was later changed to the currently valid Cephaloscyllium ventriosum (Garman 1880). The genus name Cephaloscyllium is derived from the Greek “kephale” meaning head and “skylla” meaning a kind of shark. The species name ventriosum means large belly, referring to this shark’s ability to swallow large amounts of water, doubling its body size when threatened by a potential predator. Synonyms referring to this species in past scientific literature include Cephaloscyllium uter Jordan & Gilbert 1896 and Catulus uter Jordan & Gilbert 1896.

Revised by: Macey Siegel and Tyler Bowling 2020

Prepared by: Cathleen Bester

References

- Castro, J.I., 1983. The sharks of North American waters (Vol. 1). College Station: Texas A & M University Press.

- Compagno, L.J., 1984. FAO species catalogue. v. 4:(2) Sharks of the world. An annotated and illustrated catalogue of shark species known to date, pt. 2: Carcharhiniformes.

- Cox, D.L. and Koob, T.J., 1993. Predation on elasmobranch eggs. Environmental Biology of Fishes, 38(1-3), pp.117-125.

- Ferry-Graham, L., 1997. Feeding kinematics of juvenile swellsharks, Cephaloscyllium ventriosum. Journal of Experimental Biology, 200(8), pp.1255-1269.

- Grover, C.A., 1974. Juvenile denticles of the swell shark Cephaloscyllium ventriosum: function in hatching. Canadian Journal of Zoology, 52(3), pp.359-363.