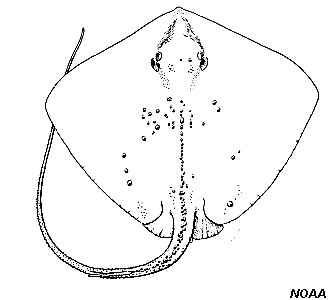

Roughtail Stingray

Dasyatis centroura

This is the largest of the whip-tail stingrays, growing over 7 feet wide and more than 660 pounds. Its diamond-shaped disc is dark brown or olive above and almost white below. The tail is black, and can be two and a half times the length of its body. Caution is suggested when interacting with the roughtail stingray, because although it is not aggressive, it has poisonous serrated tail spines, and a row of thorny tubercles down its spine and tail. It lives deeper than the casual beach-goer would normally encounter, but off-shore sports fishers and divers might encounter this stingray.

Order – Rajiformes

Family – Dasyatidae

Genus – Dasyatis

Species – centroura

Common Names

D. centroura is commonly referred to as the roughtail stingray in English-speaking countries. Internationally, it is referred to as akanthotrygona (Greek), arrai-prego (Portuguese), boll denbuh ahrax (Maltese), denizkedisi baligi (Turkish), escurcana clavellada (Catalan), essan (Fon GBE), gestekelde pijlstaartrog (Dutch), ignelivatoz baligi (Turkish), neshtelie (Albanian), ogoncza zachodnia (Polish), ozouin (Fon GBE), pastenague à queue épineuse (French), pastenague des îles (French), pastenague épineuse (French), pohjankeihäsrausku (Finish), raia-prego (Portuguese), ratão (Portuguese), raya látigo lija (Spanish), rayalátigo isleña (Spanish), rina baligi (Turkish), ruhalet pilrokke (Danish), stechrochen (German), taggspjutrocka (Swedish), tratra (Pila), trigone (Italian), trigone spinoso (Italian), trnucha hruboocasá (Czech), uge de cardas (Portuguese), uja (Creole, Portuguese), and uje-de-cardas (Portuguese).

Importance to Humans

The wings of the roughtail stingray are edible to humans; they can be found on the market fresh, smoked, and dried-salted. The ray can also be used for fishmeal and oil.

Danger to Humans

The roughtail stingray does not attack people; however, if it is stepped on it will defend itself by using its tail spines. The tail spines are poisonous, yet it is rarely life-threatening to humans.

Conservation

> Check the status of the roughtail stingray at the IUCN website.

The IUCN is a global union of states, governmental agencies, and non-governmental organizations in a partnership that assesses the conservation status of species. The roughtail stingray is listed as “Vulnerable” on the World Conservation Union (IUCN) Red List.

Geographical Distribution

The roughtail stingray is typically found in tropical to warm temperate waters of the North Atlantic. In the eastern Atlantic it occurs from the southern Bay of Biscay to Angola and in the Mediterranean Sea. In the western Atlantic it can be found from Georges Bank in Massachusetts to southern Florida and in the northeastern Gulf of Mexico and the Bahamas. There have also been reports of this ray off Uruguay and southern Brazil.

Habitat

The roughtail stingray generally dwells in muddy and sandy substrate. It can be found at a depth of up to 656 feet (200 m) and in temperatures of 59 to 79°F (15 to 26°C). Temperature is believed to be the major factor in the distribution of this ray. It is a visitor to coastal waters, bays, and estuaries during the warmer months of the year and is also found in northern waters during this time.

Biology

Distinctive Features

The most distinguishable characteristic of the roughtail stingray is its tail, which contains numerous rows of small thorns and is long, slender, and whip-like. The tail is about two and a half times the length of the body. This ray also has tubercles on the outer parts of its disc and mid-dorsal bucklers, which are large and widely spaced. This ray has a trapezoid- shaped disc with an anterior margin that is straight to slightly concave, a posterior margin that is slightly convex, and outer corners that are abruptly rounded. The snout is moderately long and angular with an obtuse tip. This ray lacks a dorsal fin fold, and the ventral fin fold on its tail is long, narrow, and not easily seen.

Coloration

The roughtail stingray is of a dark brown or olive color dorsally, is white or nearly white ventrally, and lacks dark edgings. The tail is black from the spine rearward.

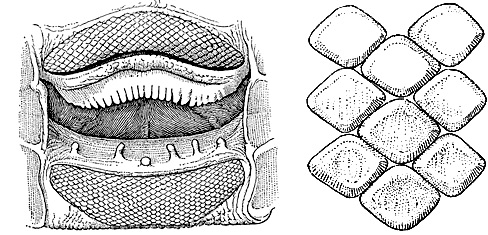

Dentition

There are about seven rows of functional teeth in the center of the upper jaw of the roughtail stingray and about twelve to fourteen functional rows in the center of the lower jaw. The cusps of the juveniles’ and females’ teeth are flat or rounded while the cusps of the mature males’ teeth are low and conical. The bases of the teeth are tetragonal, regardless of age or sex.

Dermal Denticles

Roughtail stingrays with a disc width of about 20 inches (51 cm) or greater have denticles on the tip of their snout, behind their spiracle, on the base of their tail, and on the posterior corner of their disc. Specimens with a disc width less than 20 inches (51 cm) do not posses denticles.

Size, Age & Growth

The maximum disc width and weight of the roughtail stingray is 87 inches (221 cm) and around 660 pounds (300 kg), making it the largest whip-tail stingray of the Atlantic. Males mature at a disc width of 51 to 59 inches (130 to 150 cm), while females mature at a disc width of 55 to 63 inches (140 to 160 cm). At birth, the disc width of the ray ranges from 13.5 to 14.5 inches (34 to 37 cm).

Food Habits

Common prey of the roughtail stingray consists of bony fishes, such as scup and sand lance, and of bottom-dwelling invertebrates, such as polychaetes, cephalopods, and crustaceans.

Reproduction

The roughtail stingray is ovoviviparous. This ray reproduces once per year, usually in the autumn or early winter. The embryos initially feed on yoke, and then absorb uterine fluid from the mother. The gestation period lasts about four months with the production of two to four offspring.

Taxonomy

This ray was originally described as Raja centroura (Mitchill, 1815), but was changed to Dasyatis centroura (Mitchill, 1815). Dasyatis is derived from the Greek word “dasys” which means rough, and centroura is derived from the Greek word “centoro” which means pricker. In the past it has also been referred to as Dasyatis aspera Cuvier 1816, Pastinaca aspera Cuvier 1815, Trygon aldrovandi Risso 1827, Raia gesneri Cuvier 1829, Trygon brucco Bonaparte 1834, Trygon thalassia Muller and Henle 1841, Dasyatis hastata non DeKay 1842, Pastinaca hasta non DeKay 1842, Pastinaca acanthura Gronow 1854, Trygon spinosissima Duméril 1865, and Dasybatus marinus Garman 1913.

Prepared by: Dane Eagle