Mitsukurina owstoni

Not a great deal is known about this rare shark. Living in the deep ocean, the goblin shark catches prey by quickly projecting its jaw forward. This feature and its large extended snout prompted its fearsome name.

Order – Lamniformes

Family – Mitsukurinidae

Genus – Mitsukurina

Species – owstoni

Common Names

- English: goblin shark, elfin shark

- Afrikaans: kabouterhaai

- Czech: žralok škriatok

- Danish: naesehaj

- Dutch: Japanese neushaai, kabouterhaai, koboldhaai, neushaai, schoffelneushaai, squalo folletto

- Finnish: hiisihai, karsahai

- French: requin lutin

- German: Japanischer nasenhai, koboldhai, nasenhai, teppichhai

- Icelandic: lensuháfur

- Italian: squalo goblin

- Japanese: mitsukurizame, teguzame, zoozame

- Norwegian: nesehai

- Portuguese: tubarão-demónio, tubarão-gnomo

- Spanish: tiburón duende

- Swedish: näshaj, trollhaj

Importance to Humans

Caught only as a bycatch of deepwater trawls, longlines, and deep-set gill nets. The meat is rarely sold. A specimen was displayed in Yokohama aquarium in Japan, but only survived a week.

Danger to Humans

The goblin shark seldom comes in contact with humans; however, because of its large size, it could be potentially dangerous.

Conservation

The IUCN lists this species as “Least concern”. As it is rarely encountered by fishermen and no major market for them exists.

> Check the status of the goblin shark at the IUCN website.

The IUCN is a global union of states, governmental agencies, and non-governmental organizations in a partnership that assesses the conservation status of species.

Geographical Distribution

Believed to be widely distributed, specimens have been seen in the Atlantic off the coast of Guyana, Surinam, French Guyana, France, Madeira, Senegal, Portugal, Gulf of Guinea, and South Africa. It has also been reported in the western pacific off Japan, Australia, and New Zealand. In the Indian Ocean specimens have been found in South Africa and Mozambique (Castro, 2011). The majority of reports come from Japan. It was recently recorded in the United States near San Clemente Island off the coast of California (Larson and Lowry, 2017) as well as in the northern Gulf of Mexico south of Pascagoula, Mississippi (Parsons et al., 2002). Few specimens have ever been caught making it one of the rarest sharks.

Habitat

This mesopelagic species is found along outer continental shelves, and seamounts. Smaller specimens have been seen near the surface in open water. However most specimens have been observed near continental slopes between 270-960 m (3150 ft or 0.6 miles). The deepest recorded individual was from 1,300 m (4265 feet or 0.8 miles) deep (Compagno, 2002).

Biology

Distinctive Features

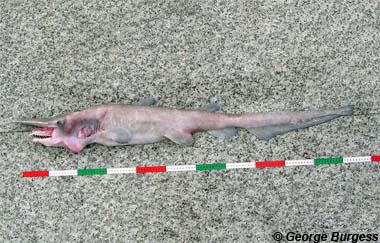

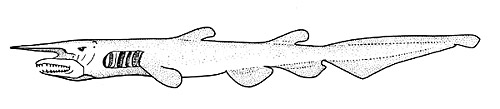

Easily identified by its elongated and flattened snout. It has a distinctly long head, tiny eyes, and five short gill openings. The mouth is large and parabolic in shape. Its body is soft and flabby. This shark has a long caudal fin without a ventral lobe, and a notch near the terminus. The pectoral fins are short and broad and the two dorsal fins are small, rounded and equal in size. The pelvic and anal fins are rounded and larger than the dorsal fins (Compagno, 2002; Last and Stevens, 2009; Castro, 2011).

Coloration

Blood vessels are visible through the skin, making them appear a pinkish white. Fins, however, appear blueish-grey. The young on are a ghostly white, with the pink color intensifying with age. Specimens fade and brown when preserved in alcohol (Castro, 2011).

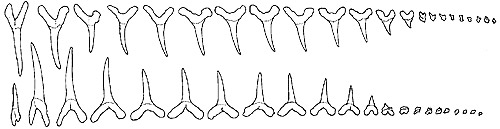

Dentition

The upper jaw has 35-53 long, narrow, finely grooved lengthwise teeth, the lower 31-62. They have three rows of anterior teeth on each side of both jaws. Rear teeth are smaller and are flattened for crushing. Some individuals have gaps separating their upper lateral teeth (Compagno, 2002; Last and Stevens, 2009; Castro, 2011).

Denticles

Small crowns with narrow cusps and ridges (Castro 2011). The cusps of the lateral denticles occur perpendicular to the skin.

Size, Age, and Growth

Previously thought to only reach 300-400 cm (9.8 and 13.1 ft) long (Castro, 2011). However, recent specimens have suggested the species may reach larger sizes. Regression analysis from photographs suggest measurements of 540 to 617 cm (18-20 ft.), all though this true maximum size of the species is still unknown (Parsons et al. 2002). Mature male specimens have ranged from 264-384 cm (9-13 ft.) mature females have measured 335-372 cm (11-12 ft) (Duffy et al., 2004). Size at birth is not known, but the smallest specimen ever collected was 107 cm (3.51 ft.) (Castro, 2011).

Food Habits

The jaws are highly modified, allowing for rapid projection to capture prey. Being thrust forward by a double set of ligaments at the mandibular joints. When the jaws are retracted the ligaments are stretched and become relaxed while projected forward. The jaws are usually held tightly while swimming. Its slender narrow teeth suggest it mainly feeds on soft body prey such as shrimps, octopus, fish, and squid. It is also thought to feed on crabs, because of posterior crushing teeth (Duffy, 1997; Yano et al., 2007; Castro, 2011).

Reproduction

The goblin shark is thought to be ovoviviparous; however, a pregnant female has never been captured (Castro, 2011).

Parasites

Tapeworms Litobothrium amsichensis and Marsupiobothrium gobelinus have been documented in the species intestines (Caira, and Runkle, 1993). The copepod Echthrogaleus mitsukurinae has been documented as well (Izawa, 2012).

Taxonomy

The goblin shark was first described in 1898, by Jordan, as Mitsukurina. This genus has been synonymized with the fossil Scapanorhynchus described by Woodward, 1889. The relationship between the two genus has been debated. Currently, the Mitsukurina family includes Mitsukurina owstoni and the fossil species of Scapanorhynchus andAnomotodon. Other synonymous names include Odontaspis nautus Branganza 1904, Scapanorhynchus jordani Hussakof 1909, and Scapanorhynchus dofleini Engelhardt 1912.

Revised by: Tyler Bowling 2019

Prepared by: Vanessa Jordan

References

- Caira, J.N.; Runkle, L.S. 1993. 2 new tapeworms from the goblin shark Mitsukurina owstoni off Australia. Systematic Parasitology. 26 (2): 81–90.

- Castro, J.H. 2011. The Sharks of North America. Oxford University Press. pp. 202–205.

- Compagno, L.J.V. 2002. Sharks of the World: An Annotated and Illustrated Catalogue of Shark Species Known to Date (Volume 2). Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. pp. 68–71.

- Duffy, C.A.J., Ebert, D.A., Stenberg, C. 2004. Mitsukurina owstoni. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. IUCN.

- Duffy, C.A.J. 1997. Further records of the goblin shark, Mitsukurina owstoni (Lamniformes: Mitsukurinidae), from New Zealand. New Zealand Journal of Zoology. 24 (2): 167–171.

- Izawa, K. 2012. Echthrogaleus mitsukurinae sp. nov (Copepoda, Siphonostomatoida, Pandaridae) infesting the goblin shark Mitsukurina owstoni Jordan, 1898 in Japanese waters. Crustaceana. 85 (1): 81–87.

- Jordan, D.S. 1898. Description of a species of fish (Mitsukurina owstoni) from Japan, the type of a distinct family of lamnoid sharks. Proceedings of the California Academy of Sciences (Series 3) Zoology. 1 (6): 199–204.

- Larson, S.E. and Lowry, D., 2017. Northeast Pacific Shark Biology, Research and Conservation (Vol. 77). Academic Press.

- Last, P.R.; Stevens, J.D. 2009. Sharks and Rays of Australia (second ed.). Harvard University Press. pp. 156–157.

- Parsons, G.R., Ingram Jr, G.W. and Havard, R., 2002. First record of the goblin shark Mitsukurina owstoni, Jordan (Family Mitsukurinidae) in the Gulf of Mexico. Southeastern Naturalist, 1(2), pp.189-192.

- Yano, K.; Miya, M.; Aizawa, M.; Noichi, T. 2007. Some aspects of the biology of the goblin shark, Mitsukurina owstoni, collected from the Tokyo Submarine Canyon and adjacent waters, Japan. Ichthyological Research. 54 (4): 388–398.