Mugil cephalus

This elongated grayish olive-brown fish appears striped because of the spots on each of its scales on its upper sides. They can grow to over 47 inches and more than 17 pounds, and like to school together for safety. Adults live in coastal fresh water, but they have a high tolerance for a range of salinity, especially since they head out to sea in large schools to spawn. Mullet are known to leap out of the water often, and it is believed this helps clear their gills and give them an oxygen boost in oxygen-poor water.

Order – Perciformes

Family – Mugilidae

Genus – Mugil

Species – cephalus

Common Names

English language common names include striped mullet, black mullet, black true mullet, bright mullet, bully mullet, callifaver mullet, common grey mullet, common mullet, flathead grey mullet, flathead mullet, gray mullet, haarder, hardgut mullet, mangrove mullet, mullet, river mullet, sea mullet, and springer. Other common names include aalder (Dutch), agwas (Tagalog), aitam (Carolinian), albur (Spanish), aligasin (Tagalog), anace (Fijiian), antafa (Malagasy), antendro (Malagasy), anubah (Arabic), araaby (Arabic), asfatiya (Arabic), asubi (Tagalog), auaree (Rapa), banak (Tagalog), belanak (Malay), beyah (Arabic), biah (Arabic), biyah (Arabic), bora (Japanese), bouri (Arabic), caanood (Somali), cabezudo (Spanish), cabot (French), cachamba (Spanish), cagarraz (Portuguese), calmou (Papiamento), cap pla (Spanish), capiton (Spanish), carida (French), caridou (French), carmou (Papiamento), cefalo (Italian), cefalo mazzone (Italian), cephalos (Greek), chefal (Rumanian), cipal glavas (Serbian), cipli (Serbian), cremole (French), deem (Wolof), diklipharder (Dutch), eirigo-do-rio (Portuguese), galupe (Spanish), gawafa (Arabic), gereh (Javanese), gerita (Malay), gerpuh (Javanese), gharyb (Arabic), gis (Wolof), glavati cipelj (Slovene), gutarana (Arabic), harder (German), haskefal baligi (Turkish), ilissa lobarrera (Spanish), is barri godeya (Sinhalese), jabaay (Wolof), jompo (Malagasy), jumpul (Malay), juovakeltti (Finnish), kahaha (Hawaiian), kanahe (Tongan), kapae (Tahitian), kapiiyut (Palicur), kaplat (Maltese), kasmeen (Tamil), kedera (Malay), kefal (Turkish), keffal (Bulgarian), kifon gdol hazosh (Hebrew), kitheya (Sinhalese), koto (Fijiian), kunungui (Krio), laban (Rumanian), laiguan-asut (Carolinian), lebranche (Spanish), lisa (Spanish), lisa cabezuda (Spanish), lisa pardete (Spanish), lissa amaria (Spanish), liza cabezona (Spanish), lizarra (Spanish), lizza (Spanish), llissa llobarrera (Catalan), loban (Russian), lombbie (Krio), ma sek (Krio), maalan (Kumak), machu (Spanish), machuto (Spanish), manalei (Tamil), manla (Tamil), meuil (French), m’hizi (Komoro), miil-budhi-dhirr (Tokelaluan), mile (Creole/French), mkizi(French), mollit (Krio), morski cefal (Bulgarian), muge cabot (French), mugem (Portuguese), muggine (Italian), mugil (Spanish), mugil australijski (Polish), mugil cefal (Polish), mugo fangous (French), mujou (French), mule (Spanish), mulet (French), mulet cabot (French), mulet jaune (French), mulet-cabot (French), mulett (Maltese), multe (Danish), muxo (Spanish), naxoc (Kumak), nyarongue (Portuguese), olhal (Portuguese), olhalvo (Portuguese), pahaha (Hawaiian), papalvo (Portuguese), pardete (Spanish), platkopharder (Afrikaans), poisson queue bleue (French), pordete (Spanish), pua (Hawaiian), pua’ama (Hawaiian), qefulli i veres (Alabanian), rapang (Malay), sibo (Portuguese), sinal (Wolof), storhovad multe (Swedish), tagana (Portuguese), tainha (Portuguese), tainha cabeca achatada (Portuguese), tainha-olhalvo (Portuguese), talilong (Tagalog), testard (French), testu (French), thel godeya (Sinhalese), tororaka (Malagasy), tshulwa (Portuguese), wu tau (Cantonese), wu tau tze (Cantonese), wutsuma (Portuguese), and zompona (Malagasy).

Importance to Humans

Along the Florida gulf coast, the striped mullet is regarded as an excellent food fish. They are also used as bait for a variety of fishes, including billfish, commonly bringing a higher price as bait than as food fish. In fresh and brackish waters, they are caught with a hook and line. Popular bait includes earthworms, oatmeal, and chicken feed. Mullet caught in freshwater often have a muddy or sulfide-like taste. In saltwater areas, mullet are snagged with hooks or captured with cast nets, seines, gill nets, or trammel nets. A net ban has been in effect in the state of Florida since 1995. Prior to the net ban amendment, mullet were severely overfished throughout the state. Currently, mullet are on the road to full recovery. Large numbers of mullet are taken during the migration to spawning grounds offshore. These fish are prized for their roe. The striped mullet is marketed fresh, dried, salted, and frozen with the roe sold fresh or smoked. This fish is also used in Chinese medicinal practices. It is a very important commercial fish in many other parts of the world.

Conservation

The striped mullet is not listed as endangered or vulnerable with the World Conservation Union (IUCN). The IUCN is a global union of states, governmental agencies, and non-governmental organizations in a partnership that assesses the conservation status of species.

> Check the status of the striped mullet at the IUCN website.

Geographical Distribution

The striped mullet is cosmopolitan throughout coastal tropical to warm temperate waters. In the western Atlantic Ocean, it is found from Nova Scotia, Canada south to Brazil, including the Gulf of Mexico. It is absent in the Bahamas and the Caribbean Sea. In the eastern Atlantic Ocean, the striped mullet occurs from the Bay of Biscay (France) to South Africa, including the Mediterranean Sea and the Black Sea. The eastern Pacific Ocean range includes southern California south to Chile.

Habitat

This is a coastal species that often enters estuaries and freshwater environments. Adult mullet have been found in waters ranging from 0 ppt to 75 ppt salinity while juveniles can only tolerate such wide salinity ranges after they reach lengths of 1.6-2.8 inches (4-7 cm). Adults form huge schools near the surface over sandy or muddy bottoms and dense vegetation. They migrate offshore to spawn in large aggregations. The larvae move inshore to extremely shallow water which provides cover from predators as well as a rich feeding ground. After reaching 2 inches (5 cm) in length, these young mullet move into slightly deeper waters. Striped mullet leap out of the water frequently. Biologists aren’t sure why these fish leap so often, but it could be to avoid predators. Another possibility is that the fish spend much time in areas that are low in dissolved oxygen. They may quickly exit the water in order to clear their gills and be exposed to higher levels of oxygen.

Biology

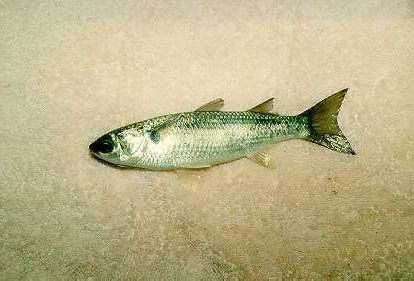

Distinctive Features

The body of the striped mullet is subcylindrical and anteriorly compressed. It has a small, terminal mouth with inconspicuous teeth and a blunt nose. The lips are thin, with a bump at the tip of the lower lip. The adipose eyelid is prominent with only a narrow slit over the pupil. The body is elongate and the head is a slightly wider than deep. Pectoral fins are short, not reaching the first dorsal fin. The origin of the second dorsal fin is posterior to the origin of the anal fin. The lateral line is not visible.

This mullet is often confused with the white mullet, Mugil curema. However, the white mullet has scales extending onto its soft dorsal and anal fins while the striped mullet does not. They may also be identified based on the anal ray fin counts of 8 for the striped mullet and 9 for the white mullet.

Coloration

The body is grayish olive to grayish brown, with olive-green or bluish tints and sides fading to silvery white towards the belly. Dark longitudinal lines, formed by dark spots at the center of each scale on the upper half of the body, run the length of the body. Young fish smaller than 6 inches (15 cm) in length lack stripes. There is a large dark blotch at the base of the pectoral fin. The pigmentation in the iris is dispersed and brown, a character that also helps to distinguish it from Mugil curema.

Dentition

The mouth is triangular in shape when viewed from above, with small, close-set teeth arranged in several rows on the jaws.

Size, Age, and Growth

The maximum length of the striped mullet is 47.2 inches (120 cm), with a maximum weight of 17.6 pounds (8 kg). Lifespan is reported to range somewhere between 4 and 16 years. Maturity is attained at approximately 3 years of age, corresponding to lengths of 7.9-11.8 inches (20-30 cm). Females mature at a slightly larger size than males. Growth rates along the gulf coast of Florida increase from west to east, from the panhandle along the peninsula, probably due to the temperature increase. Most growth occurs during the spring and summer months. Adults grow at a rate of 1.5-2.5 inches (3.8-6.4 cm) per year. Females are larger and grow faster than males of the same age.

Food Habits

Mullet are diurnal feeders, consuming mainly zooplankton, dead plant matter, and detritus. Mullet have thick-walled gizzard-like segments in their stomach along with a long gastrointestinal tract that enables them to feed on detritus. They are an ecologically important link in the energy flow within estuarine communities. Feeding by sucking up the top layer of sediments, striped mullet remove detritus and microalgae. They also pick up some sediments which function to grind food in the gizzard-like portion of the stomach. Mullet also graze on epiphytes and epifauna from seagrasses as well as ingest surface scum containing microalgae at the air-water interface. Larval striped mullet feed primarily on microcrustaceans. One study found copepods, mosquito larvae, and plant debris in the stomach contents of larvae under 35mm in length. The amount of sand and detritus in the stomach contents increases with length indicating that more food is ingested from the bottom substrate as the fish matures.

Reproduction

The striped mullet is catadromous, that is, they spawn in saltwater yet spend most of their lives in freshwater. During the autumn and winter months, adult mullet migrate far offshore in large aggregations to spawn. In the Gulf of Mexico, mullet have been observed spawning 40-50 miles (65-80 km) offshore in water over 3,280 feet (1,000 m) deep. In other locations, spawning has been reported along beaches as well as offshore. Estimated fecundity of the striped mullet is 0.5 to 2.0 million eggs per female, depending upon the size of the individual.

The eggs are transparent and pale yellow, non-adhesive, and spherical with an average diameter of 0.72mm. Each egg contains an oil globule, making it positively buoyant. Hatching occurs about 48 hours after fertilization, releasing larvae approximately 2.4mm in length. These larvae have no mouth or paired fins. At 5 days of age, they are approximately 2.8mm long. The jaws become well-defined and the fin buds begin to develop. At 16-20mm in length, the larvae migrate to inshore waters and estuaries. At 35-45mm, the adipose eyelid is obvious, and by 50mm it covers most of the eye. At this time the mullet is considered to be a juvenile. These juveniles are capable of osmoregulation, being able to tolerate salinities of 0-35 ppt. They spend the remainder of their first year in coastal waters, salt marshes, and estuaries. In autumn, they often move to deeper water while the adults migrate offshore to spawn. However, some young mullet overwinter within the estuaries. After this first year of life, mullet inhabit a variety of habitats including the ocean, salt marshes, estuaries, and fresh water rivers and creeks.

Predators

Major predators of the striped mullet include fishes, birds, and marine mammals. Spotted seatrout (Cynoscion nebulosus) feed on mullet up to 13.8 inches (35 cm) long. Off the coast of Florida, sharks often feed on large mullet. Pelicans and other aquatic birds as well as dolphins also prey on the striped mullet.Parasites

Mullet commonly have parasitic infestations. In one study, nearly 300 adult mullet were collected from Florida’s gulf coast. All individuals contained parasites. The striped mullet are hosts for many parasites including flagellates, ciliates, myxosporidians, monogenean and digenean trematodes, nematodes, acanthocephalans, leeches, argulids, copepods, and isopods. Young mullet below 8 inches (20cm) in length are often heavily infested by adult digenetic trematodes while larger hosts have primarily myxosporidians, copepods, and nematodes as well as larval digenean trematodes. Heavily parasitized specimens carrying large amounts of one parasite, often were host to the greatest number of parasitic species. Apparently already weakened hosts are more vulnerable to infestation by other parasites.

Taxonomy

Carl Linnaeus, a Swedish naturalist, originally described the striped mullet as Mugil cephalus in 1758. The genus name Mugil is derived from the Latin “mugil” meaning a fish, probably a mullet. The species name cephalus is derived from Latin meaning a mullet. Synonyms referring to this fish include Mugil albula Linnaeus, 1766, Mugil ourForsskal, 1775, Mugil crenilabis our Forsskal, 1775, Mugil tang Bloch, 1794, Mugil provensalis Risso, 1810, Mugil lineatus Valenciennes, 1836, Mugil cephalotus Valenciennes, 1836, Mugil japonicus Temminck and Schlegel, 1845, Mugil dobula Gunther, 1861, Mugil ashanteensis Bleeker, 1863, Mugil cephalus ashanteensis Bleeker, 1863, Myxus superficialis Klunzinger, 1870, Mugil gelatinosus Klunzinger, 1872, Mugil occidentalis Castelnau, 1873, Mugil mexicanus Steindachner, 1876, Myxus caecutiens Gunther, 1876, Mugil grandis Castelnau, 1879, Mugil muelleri Klunzinger, 1880, Mugil mulleri Klunzinger, 1880, Mugil hypselosoma Ogilby, 1897, Myxus pacificus Steindachner, 1900, and Myxus barnardi Gilchrist and Thompson, 1914.

Prepared by: Cathleen Bester