Mangrove Rivulus

Rivulus marmoratus

These tiny fish can survive for up to two months in wet leaves, logs, small puddles, and crab burrows, ‘breathing’ through their skin. They flip head-over-tail across land to travel to better locations. Mostly hermaphrodites, they are able to fertilize their own eggs, a trait probably developed from living in isolated places. Because of its reproduction and life span, this is a very practical fish in labs to study toxicity and pollutants.

Order – Cyprinodontiformes

Family – Aplocheilidae

Genus – Rivulus

Species – marmoratus

Common Names

Mangrove rivulus, manatanzas rivulus, and rivulus are common English names that refer to R. marmoratus. Other common names include kamulibo (Galibi), loangouma (Djuka), marmorierter (German), toumblouc (French/Creole), and wilili (Oyampi).

Importance to Humans

Because of its genetic homozygosity, this fish is often the subject in toxicology and genetic research. The mangrove rivulus is easy to maintain in captivity and produce siblings that are nearly genetically identical. Along with a short life cycle, these characteristics make this fish ideal for toxicity studies of potential pollutants.

Conservation

The mangrove rivulus was once listed as a threatened species in the Gulf of Mexico. However, recently additional surveys have revealed the existence of numerous populations. In Florida it has been downlisted as a species of special concern. In 1999, the mangrove rivulus was submitted by the National Marine Fisheries Service as a candidate for protection under the Endangered Species Act. As of yet, it has not been officially listed as endangered or threatened.

It is currently considered a species of “Lower Risk/Least Concern” by the World Conservation Union (IUCN) although this classification was determined in 1996 and is noted as “out of date”. The IUCN is a global union of states, governmental agencies, and non-governmental organizations in a partnership that assesses the conservation status of species.

> Check the status of the mangrove rivulus at the IUCN website.

The main threat to the survival of the mangrove rivulus is habitat degradation and destruction as well as exposure to pollutants. Disturbances that alter salinity and temperature as well as vegetation cover may also reduce naturally occurring populations of the mangrove rivulus.

Geographical Distribution

The mangrove rivulus is found in the tropical and subtropical portions of the western Atlantic/Caribbean basin from central Florida to the Bahamas and Caribbean, south to Brazil including the Yucatan and Venezuela. This range closely parallels that of the range of the red mangrove (Rhizophora mangle), the preferred habitat of the mangrove rivulus. Its most northern range is Florida, where it is locally rare. Within the state of Florida, it is found along the Atlantic coast, north to Indian River County and south throughout all of the Keys. On the western coast, the mangrove rivulus may be found north almost to Ft. Myers. The mangrove rivulus is the widest ranging member of the genus.

Habitat

The mangrove rivulus is primarily a saltwater or brackish water species, with limited occurrence in freshwater. It can tolerate salinities from 0-68 parts per thousand. Within the Everglades and along Florida’s west coast, this fish occurs in stagnant, seasonal ponds and sloughs as well as in mosquito ditches within mangrove habitats. Along the east coast of Florida, it resides in elevated marsh habitats above the intertidal zone, often within the burrows of the great land crab (Cardisoma guanhumi). This preferred microhabitat may provide shelter from cool winter temperatures, allowing for a more northerly distribution of what would otherwise be possible. Great land crab burrows also provide areas of refuge during the dry season, when seasonal pools of water dry up. Fish occurring in these burrows are small, with as many as 26 fish having been recorded in a single burrow. Burrows of other crab species may be utilized when the giant land crab is absent, particularly in areas of the west Florida coast. The mangrove rivulus is able to survive in moist detritus without water for up to 60 days during periods of drought, anaerobic, or high sulfide conditions. Intraspecific aggression may also induce individuals to move to other bodies of water. This fish has been observed slithering and flipping across land during the rainy season to reach pools of water or crab burrows containing water. Epidermal capillaries are used for respiratory gas exchange during times of adverse environmental conditions. Tolerating extremes in temperature and salinity, the mangrove rivulus survive in areas where few other fish species can exist. Competitively inferior to other carnivorous fish, it avoids direct competition by residing in the harsh upper intertidal zones of mangrove habitats.

Biology

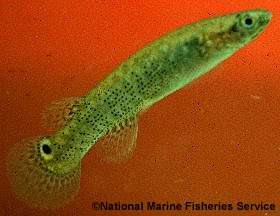

Distinctive Features

The mangrove rivulus has an elongate, slender, dorso-ventrally flattened body with a rounded caudal fin. Both dorsal and anal fins are set well back on the body with the origin of the dorsal fin directly posterior to the anal fin.

Coloration

The head and body are maroon to dark brown or tan, with small dark spots and speckling on the body, particularly the sides. The dorsal surface is always darker than the creamy ventral surface. The color of the body is reflective of the habitat, with light coloration in areas of light colored sediments and darker coloration in environments with dark leaf litter substrates. A large dark spot surrounded by a band of yellow is located at the upper base of the caudal fin in hermaphroditic individuals. Males lack this dark spot and have a red-orange cast to their flanks and fins.

Size, Age & Growth

This fish can reach a maximum size of 2 inches (5 cm) in length, however it is more commonly observed at lengths between 0.4-1.5 inches (1.0-3.8 cm). Sexual maturity is attained by hermaphroditic fish at 90 days and primary males at 84 days of age. Sexes can be distinguished 8 weeks after fertilization of the egg occurs. Adults may live up to 5 years of age in captivity; lifespan for naturally occurring individuals is unknown.

Food Habits

Feeding on terrestrial and aquatic invertebrates, this carnivorous fish feeds heavily when its habitat becomes flooded. Otherwise, it is an opportunistic feeder when confined to crab burrows. Ants and flying insects as well as aquatic invertebrates such as polychaete worms, gastropods, mollusks, and mosquito larvae make up the majority of the mangrove rivulus diet. The mangrove rivulus has been observed jumping out of the water to capture termites, returning to the water to swallow its prey. It may also be cannibalistic, feeding on other mangrove rivulus, while living in crab burrows containing very limited food resources.

Reproduction

Functioning as hermaphrodites, the mangrove rivulus is able to fertilize their own eggs internally, producing viable offspring. Each hermaphroditic fish produces both sperm and eggs in it ovotestes. It is the only natural example of cloning by a vertebrate organism. Males are rarely observed in the wild in Florida, but are more common throughout the Caribbean and Central America. There are two types of males, primary and secondary. Primary males develop directly from fertilized eggs while secondary males develop from hermaphroditic fish under certain environmental conditions. There is evidence that young fish sexually outcross, releasing unfertilized eggs, with the occurrence of both males and females in wild populations. There may be an age-dependent shift in sex allocation, from female-dominated to one that is hermaphroditic-dominated as older populations have significantly higher numbers of hermaphroditic fishes. This hermaphroditic mode of reproduction may be an evolutionary response to the habitation and possible isolation within crab burrows.

Mature eggs are released near the surface of the water during different stages of development, ranging from those that have been recently fertilized to others already containing a developing embryo. Most eggs hatch 16 days after fertilization, although some may take up to 2 weeks longer. In the meantime, adult mangrove rivulus often eat these released eggs. The number of eggs released by each adult is dependent upon the size of the adult fish as well as the season, with the release of 40-75 eggs being typical. Fertilized eggs will only develop if incubated under damp conditions, hatching simultaneously with flooding of the mangrove.

Predators

Predators include other fish and wood storks, as well as possibly the Atlantic saltmarsh snake which is often found in crab burrows containing mangrove rivulus.

Taxonomy

Rivulus marmoratus was described by the accomplished Cuban ichthyologist, Felipe Poey in 1880. The synonym, Rivulus ocellatus Hensel, 1868 has been suppressed by the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature (Opinion 1798, Case 2722) in favor of R. marmoratus. Other synonyms include R. heyei Nichols 1914, R. marmoratus bonairensis Hoedeman, 1958, R. bonairensis Hoedeman 1958, R. garciae de la Cruz and Dubitsky 1976, and R. garciai de la Cruz and Dubitsky 1976. The mangrove rivulus is the only rivulus found in North America and its presence in our waters was only recently detected.Prepared by: Cathleen Bester