Sphyrna tiburo

Bonnetheads are one of the smaller hammerheads, and are easy distinguished by their shovel-shaped heads. These warm-water coastal sharks migrate with the seasons, and are often attractions at aquariums.

Order – Carcharhiniformes

Family – Sphyrnidae

Genus – Sphyrna

Species – tiburo

Common Names

- English: bonnethead, bonnet hammerhead, bonnet shark, bonnethead shark, bonnetnose shark, and shovelhead.

- Dutch: kaphamerhaai

- French: requin-marteau tiburo

- German: kleiner hammerhai

- Japanese: uchiwa-shumokuzame

- Polish: lopatoglów

- Portuguese: Cação, cação-chapéu, cambeva-pata, martelo, pata, peixe-martelo, rodela

- Spanish: cabeza de pala, cachona, cornuda de corona, cornuda tiburo, cornudo de corona, pex martillo, sarda cachona, tiburón bonete del Pacífico

Importance to Humans

Bonnetheads are a common inshore shark and are often caught in shrimp trawls, longlines, and by recreational anglers, though they are not targeted. The meat is marketed for human consumption as well as processed into fishmeal. Although it is marketed, this species if of little economic importance. Recreationally, bonnetheads can provide great sport on light tackle or fly fishing gear. They are often found on shallow water flats and caught on live and cut bait including crabs.

Danger to Humans

Considered harmless to humans, this species is rather shy.

Conservation

Currently, this species is categorized as a species of “Least Concern” due to its high population numbers by the World Conservation Union (IUCN). The IUCN is a global union of states, governmental agencies, and non-governmental organizations in a partnership that assesses the conservation status of species.

> Check the status of the bonnethead at the IUCN website.

Geographical Distribution

Limited to warm waters of the Northern Hemisphere, ranging in the Atlantic Ocean from New England (U.S.) (rare) south to the Gulf of Mexico and Brazil. It is common throughout the Caribbean Sea, especially Cuba, Bahamas, and occasionally in Bermuda. In the Pacific, they are found from southern California to waters off of Ecuador (Ebert et al. 2013).

During the summer bonnetheads are commonly seen in inshore waters off the Carolinas and Georgia (U.S.) while during the spring, summer, and autumn they are found off the coast of Florida and in the Gulf of Mexico. Bonnetheads travel long distances every day, following changes in the water temperature. This preference for water temperatures over 21°C (70°F) leads to migrations to warmer waters during the winter months. As a result, bonnetheads are found closer to the equator during the winter, moving back to higher latitudes during the summer (Hueter and Manire, 1994).

Habitat

Bonnetheads reside on continental and insular shelves, over reefs, estuaries and shallow bays from depths of 12 m (39 ft.) (Compagno, 1984). They usually occur in small schools of up to 15 individuals, however, during migration events they are seen in groups of hundreds or thousands. As spawning season approaches, bonnetheads tend to group by gender. During pupping season; females congregate in shallow waters, where they give birth.

Although this shark is not territorial, it appears a hierarchy exists within schools. Another interesting feature is a cerebrospinal fluid used in chemical communication among individuals, informing others when an individual is near (Rall, 1967). Further studies are needed to learn more about this communication system.

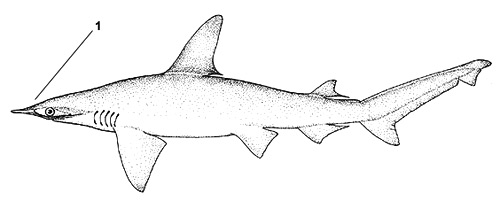

Distinguishing Characteristic

1. Head is shovel-shaped with evenly rounded between the eyes

Biology

Distinctive Features

Shovel or bonnet-shaped head, making identification easy among other hammerhead sharks. The eyes are located at the ends of the evenly rounded lobes of the flattened head, increasing the field of vision. When swimming, the head rolls from side to side. The body is moderately compact and lacks a mid-dorsal ridge. The high first dorsal fin originates just behind the base of the pectoral fins. The second dorsal fin is slightly less than half as long as the base of the first dorsal fin with a slender free rear corner. The pectoral fins are short and the anal fin has only a slight indentation. The caudal fin has a nearly straight upper margin with a lower lobe about 1/3 as long as the upper lobe with a nearly straight rear edge (Compagno, 1984).

The head lacks a notch at the midline. It is the smallest of the hammerheads (family Sphyrnidae), reaching an average of 90-120 cm (3-4 ft.), in comparison to the scalloped hammerhead which grows to an average of 183 cm (6 ft.) or the great hammerhead growing to almost 601 cm (20 ft.) in length.

Coloration

Ranges from gray to gray-brown, with occasional green tint. Dark spots are occasionally seen on the sides of the body. Viewed from the side, the color changes from top to bottom, from a lighter gray to a white underside (Compagno, 1984).

Dentition

Small, sharp teeth located in the front of the mouth used for cutting up prey and flat large molars in the back for grinding harder prey items. The sharp front teeth have short, stout cusps lacking serrations, followed by teeth with oblique cusps and then the flat molars in the back of the mouth (Compagno, 1984).

Denticles

Larger than those found in the smooth hammerhead (S. zygaena) and vary greatly in arrangement from closely overlapping to loosely spaced. The blades are steeply raised with 5 ridges with corresponding marginal teeth.

Size, Age, and Growth

Bonnetheads reach an average size of 100-120 cm (36-48 in.) with a maximum length of approximately 150 cm (59 in.) (Ebert et al., 2013; Frazier et al. 2014). Females are larger than males on average. The maximum recorded weight of a bonnethead is 10.8 kg (24 lb.). Males mature between 52-75 cm (20-30 in.) while females mature at 84 cm (33 in.) or less. Life span is estimated at 17.9 years for females and 16.0 years for males (Frazier et al., 2014).

Food Habits

Feed during daylight hours primarily on crustaceans, particularly blue crabs (Callinectes sapidus), mantis shrimp (Squilla empusa), pink shrimp (Penaeus durorarum), mollusks, and small fishes. Occasionally bonnetheads will also feed on seagrasses, especially as pups (Bethea et al., 2007). This species has been reported burrowing under coral heads in search of small fishes and invertebrates in the waters of southern Florida. Females tend to feed more often due to the need for an increased amount of energy budgeted for reproductive efforts.

Prey items appear to be correlated with seasonality as well as habitat. Although crustaceans are the primary food source throughout the year, during autumn diversity of prey items increases with the inclusion of spider crabs (Libinia dubia), purse crabs (Persephona punctata), stone crabs (Menippe mercenaria), and various cephalopods including octopus. Bonnetheads residing inside bays feed on a less diverse array of prey items than those caught off beaches in open waters.

Prey are crushed with the molariform teeth. There are two jaw-closing phases. This differs from the capture event typical of other sharks, where the jaws are initially closed and biting ceases at jaw closure. After the prey is crushed, it is moved by suction to the esophagus (Mara et al., 2010).

Reproduction

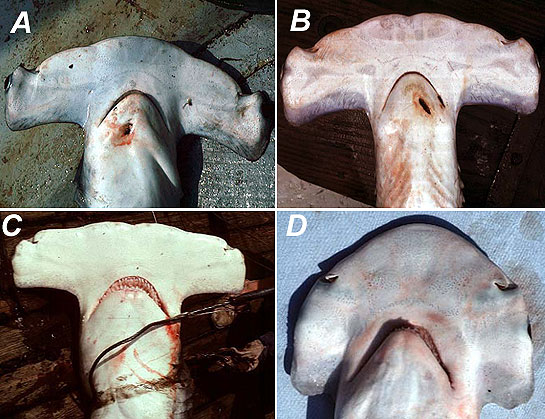

These are the only sharks known to exhibit sexual dimorphism of the head. Females have a broadly rounded cephalofoil, whereas along the anterior margin of the male cephalofoil has a large bulge. The bulge is the elongated rostral cartilage which occurs at sexual maturity along with elongation of claspers (Kajiura et al., 2005)

In Florida mating is believed to occur during spring and autumn, but may even be year-round. In the waters off the coast of Brazil, mating occurs during the spring. After mating, the females can store sperm for up to four months prior to actually fertilizing the eggs. This control over fertilization is believed to be an adaptation ensuring that the pups are born during optimal conditions for their survival (Parsons, 1993; Manire et al., 1995).

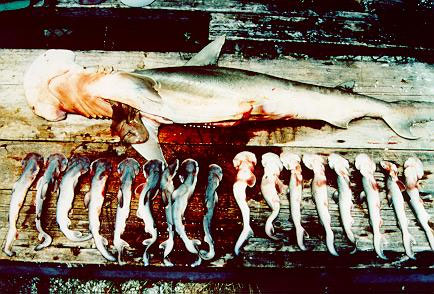

Bonnetheads are “viviparous”, or live-bearing. Female bonnetheads produce eggs that are maintained and nourished by a yolk-sac during gestation. The eggs within the female are tough but elastic with folded ends allowing for growth of the embryos. Yolk sacs attach to the uterine wall of the mother forming a yolk-sac placenta. Blood vessels running through this placenta provide nourishment until birth. Additionally, sections of the uterine wall come together to separate each embryo and its placenta in its own uterine compartment (Schlernitzauer and Gilbert, 1966). The gestation period is the shortest among all sharks, is only 4-5 months (SEDAR, 2013).

Females move to shallow inshore waters during pupping season, giving birth in late summer and early fall. Litter sizes average 4-14 pups, each approximately 21.5- 29.7 cm (0.7-1 ft.), though there are reports of individual pups born larger (Lombardi-Carlson et al., 2003; Sedar, 2013). During this time, the females lose their desire for food, which prevents them from feeding on their pups. Males move to a different location, to avoid feeding upon their own young as well. Parturition varies by latitude, taking place in mid-to-late August in Florida Bay (southernmost location), early September in Tampa Bay (middle location) and mid-to-late September off north-west Florida (northernmost location) (Lombardi-Carlson et al., 2003). The pups will live in the seagrass beds for the first years of life (Hueter and Manire, 1994; Bethea et al., 2014).

Predators

Larger sharks are potential predators of the bonnethead.

Parasites

The monogenean Erpocotyle tiburonis has been reported to cause gill lesions on bonnetheads (Bullard et al., 2001). Other parasites include copepods such as Eudactylina longispina collected from the gill filaments of a bonnethead caught in Tampa Bay, Florida. Individuals are also commonly infected with fungus, Fusarium solani (Muhvich et al., 1989).

Taxonomy

Karl Linnaeus first described this species as Sphyrna tiburo in 1758 after initially naming it Squalus tiburo. Synonyms referring to this species in past scientific literature include S. vespertina Springer 1940. The genus name Sphyrna is derived from the Greek word “sphyra” which translates as hammer.

Revised by: Tyler Bowling 2018

Prepared by: Cathleen Bester

References

- Bethea, D.M., Hale, L., Carlson, J.K., Cortés, E., Manire, C.A. and Gelsleichter, J., 2007. Geographic and ontogenetic variation in the diet and daily ration of the bonnethead shark, Sphyrna tiburo, from the eastern Gulf of Mexico. Marine biology, 152(5), pp.1009-1020.

- Bullard, S.A., Frasca Jr, S. and Benz, G.W., 2001. Gill lesions associated with Erpocotyle tiburonis (Monogenea: Hexabothriidae) on wild and aquarium-held bonnethead sharks (Sphyrna tiburo). Journal of Parasitology, 87(5), pp.972-977.

- Compagno, Leonard J.V., 1984. FAO Species Catalog, Vol. 4 Sharks of the World. United Nations Development Program, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome.

- Ebert, D.A., Fowler, S. and Compagno, L. 2013. Sharks of the World. Wild Nature Press, Plymouth.

- Frazier, B.S., Driggers, W.B., Adams, D.H., Jones, C.M. and Loefer, J.K. 2014. Validated age, growth and maturity of the bonnethead Sphyrna tiburo in the western North Atlantic Ocean. Journal of Fish Biology 85: 688-712.

- Hueter, R.E. and Manire, C.A. 1994. Bycatch and catch-release mortality of small sharks and associated fishes in the estuarine nursery grounds of Tampa Bay and Charlotte Harbor. Project Report. NOAA NMFS/ MARFIN Program NA17FF0378.

- Kajiura, S. M.; Tyminski, J. P.; Forni, J. B.; Summers, A. P. 2005. The sexually dimorphic cephalofoil of bonnethead sharks, Sphyrna tiburo. The Biological Bulletin. 209 (1): 1–5

- Lombardi-Carlson, L., Cortes, E., Parsons, G, and Manire, C. 2003. Latitudinal variation in life-history traits of bonnethead sharks, Sphyrna tiburo, (Carcharhiniformes : Sphyrnidae) from the eastern Gulf of Mexico. Marine and Freshwater Research 54(7): 875-883.

- Manire, C.A., Rasmussen, L.E.L., Hess, D.L. and Hueter, R.E. 1995. Serum steroid hormones and the reproductive cycle of the female bonnethead shark, Sphyrna tiburo. General and Comparative Endocrinology 97: 366–376.

- Mara, K.R., Motta, P.J. and Huber, D.R., 2010. Bite force and performance in the durophagous bonnethead shark, Sphyrna tiburo. Journal of Experimental Zoology Part A: Ecological Genetics and Physiology, 313(2), pp.95-105.

- Muhvich, A.G., Reimschuessel, R., Lipsky, M.M. and Bennett, R.O., 1989. Fusarium solani isolated from newborn bonnethead sharks, Sphyrna tiburo (L.). Journal of Fish Diseases, 12(1), pp.57-62.

- Parsons, G.R. 1993. Age determination and growth of the bonnethead shark Sphyrna tiburo: a comparison of two populations. Marine Biology 117: 23–31.

- Rall, G. 1967. Sharks, Skates, and Rays. Johns Hopkins Press, Baltimore, Maryland.

- Schlernitzauer, D.A. and Gilbert, P.W., 1966. Placentation and associated aspects of gestation in the bonnethead shark, Sphyrna tiburo. Journal of Morphology, 120(3), pp.219-231.

- Southeast Data, Assessment, and Review (SEDAR). 2013. SEDAR 34 Stock Assessment Report: HMS Bonnethead Shark. NOAA Fisheries, North Charleston, South Carolina, USA.