Sphyrna tudes

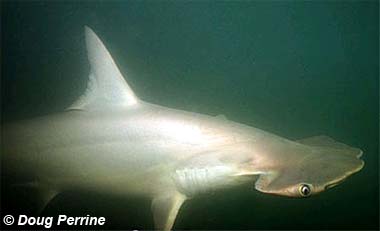

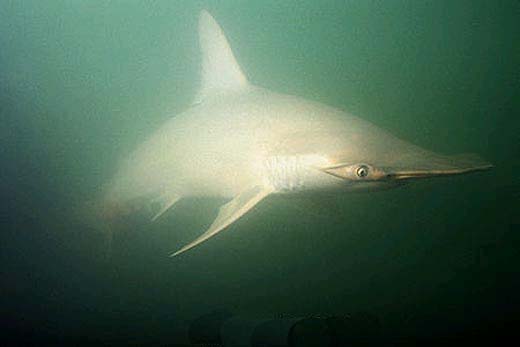

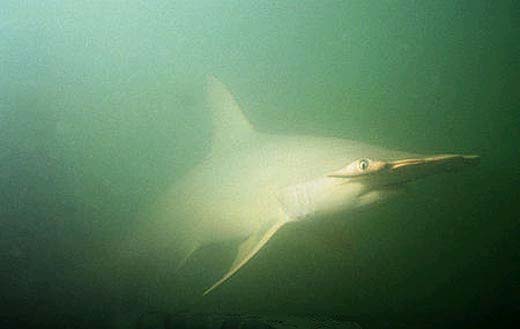

Named for its unusually small eyes, which evolved due to its preference for muddy coastal waters. Sporting a distinctly flat and arched cephalophoil, or “hammerhead”, this species is can detect prey in the murkiest of waters.

Order – Carcharhiniformes

Family – Sphyrnidae

Genus – Sphyrna

Species – tudes

Common Names

- English: curry shark, golden hammerhead

- Portuguese: cação-chapéu-armad, cação-martelo, cambeva, marteleiro, peixe-martelo, and tubarão-martelo

- Spanish: cornuda de corona, corunda ojichica, pez martillo

- Malayalam: kannankodi

- Dutch: kleinooghamerhaai

- Maltese: krozza, kurazza, kurazza rasha zghira, and pixximartell

- Greek: mikrozygena

- Italian: pesce stampella

- French: requin-marteau, petits yeux

Importance to Humans

This is one of the most abundant species along the east coast of South America and is, therefore, a significant portion of the by-catch by shrimp boat trawls and other fisheries. While the fins and meat are sold, it is not considered to be of large economic importance.

Danger to Humans

According to the International Shark Attack File, there have been 15 unprovoked attacks by the genus Sphyrna. The actual hammerhead species is often difficult to pinpoint during an attack due to only slight variations between species morphology. There has only been one reported hammerhead attack in the smalleye hammerheads home range, and it is one of the few to be identified as a scalloped hammerhead, S. lewini. All sharks have the potential to be dangerous to humans if harassed, however, the smalleye hammerhead likely poses no serious threat to humans.

Conservation

In recent years, there has been a marked decline reported in artisanal catches of smalleye hammerheads in Trinidad, this is likely a result of overfishing (Castro and Woodley 1998, Castro et al. 1999). Due to the pressures of overfishing and small litter sizes the smalleye has been labeled as “Vulnerable” on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Though no protections are currently in place.

> Check the status of the smalleye hammerhead at the IUCN website.

The IUCN (World Conservation Union) is a global union of states, governmental agencies, and non-governmental organizations in a partnership that assesses the conservation status of species.

Geographical Distribution

Found in the subtropical waters off the east coast of South America from Venezuela to Uruguay. The Orinoco delta located on the northeast coast of Venezuela has a large population, where it is thought to be the dominant species of hammerhead, as well as in the waters of northeastern Trinidad. Older reports list the species in the Mediterranean Sea and Gulf of Mexico are likely incorrect identifications for the whitefin hammerhead (S. couardi) (Cadenat and Blache, 1981).

Habitat

Muddy coastal waters, 5-40 m (16-131 ft.) in depth. Pups live in shallow waters until they reach approximately 40 cm (15.7 in.), at which point they move out into deeper waters. Juvenile and adult males tend to school with other individuals of a similar size and are found abundantly at a depths of 27-36 m (88.5-118 ft.). The adult females, however, can be found in shallower waters of 9-18 m (29.5-59 ft.) and rarely school (Castro, 1989)

Biology

Distinctive Features

Relatively long and flat cephalophoil, or “hammerhead”, with small eyes located slightly anterior to upper jaw. The species has a uniquely deep indentation in the center of the cephalophoil.

Coloration

Ranging from bright gold to a yellow-orange, its skin can have a metallic or iridescent hue. As the shark ages and reaches sexual maturity, the colors tend to fade; however, it remains a yellowish-grey color on the underside. The characteristic golden color results from a pigment present in their shrimp and catfish diet. (Castro, 1989)

Dentition

The narrowly arched jaws are filled with are long and slender teeth, which are smooth or have slightly serrated cusps (Compagno, 1984; McEachran, and Fechhelm, 1998).

Denticles

There are five distinct horizontal ridges leading to marginal teeth along each oval-shaped denticle (Gallagher, 2010).

Size, Age, and Growth

Being one of the smallest members of the family Sphyrnidae, S. tudes only reach a maximum of 150 cm (5 ft.) (Froese et al., 2008). Studies conducted off the coast of Trinidad showed males maturing at approximately 80 cm (2.6 ft.) and females at approximately 98 cm (3.2 ft.). Pups averaged near 30 cm (1 ft.) at birth (Castro, 1989). However, studies of Brazilian populations estimated size at 50% maturity for females was 114 cm (3.7 ft.). Additionally, Brazilian males were maturing at 92 cm (3 ft.). Both sexes were maturing considerably larger than the Trinidad populations (Lessa et al. 1989). The underlying cause of this difference is yet unknown.

Food Habits

Diet consists mainly of shrimp, sea catfish, swimming crabs, squid and scalloped hammerhead pups (S. lewini). Juveniles generally feed on penaeid shrimp (Xiphopenaeus kroyeri). The color of the sea catfish, their eggs and the shrimp are a very bold golden color. This has led scientists to postulate that there is a connection between the carotenoid pigment in the catfish and shrimp and the color of the shark (Castro, 1989).

Reproduction

The reproductive cycle is thought to be annual, similar to the bonnethead shark (S. tiburo). Smalleyes are viviparous, utilizing a yolk-sac placenta to nourish young until parturition. Mating occurs annually in August and September off of Trinidad. After a 10 month gestation, 5-12 pups are born in shallow coastal bays (Castro, 1989). The larger Brazilian populations, however, give birth to as many as 19 pups, breeding from June to October (Lessa et al. 1989).

Predators

As one of the smaller members of the hammerhead family, the smalleye is susceptible to becoming prey to larger sharks such as bull sharks (Carcharhinus leucas) and other hammerheads (Sphyrna spp.). Juveniles are also preyed upon by large bony fish and other sharks.

Parasites

Various copepod species, including Echthrogaleus coleoptratus, Pandarus saturus and P. cranchii, likely utilize this hammerhead as a host.

Taxonomy

Historically, there has been much confusion regarding the scientific nomenclature for the smalleye hammerhead. The name Sphyrna tudes was first applied to a smalleye hammerhead specimen in France that was originally thought to be a great hammerhead. Due to this misnomer, for many years the great hammerhead was known as S. tudes. When the smalleye hammerhead was discovered off the coast of South America it was given the name S. bigelowi. Years later, when samples of the smalleye hammerhead were compared to the French sample of the misnamed great hammerhead and discovered to be conspecific, the names were changed. The great hammerhead was then changed to S. mokkarranand the smalleye hammerhead to its present name, S. tudes. Additionally, smalleyes were misidentified in the Mediterranean Sea and the Gulf of Mexico as whitefin hammerheads (S. couardi) (Cadenat and Blache, 1981).

Revised by: Tyler Bowling 2019

Prepared by: Erin Gallagher

References

- Castro, J.I. 1989. The biology of the golden hammerhead, Sphyrna tudes, off Trinidad. Environmental Biology of Fishes 24: 3–11.

- Castro, J.I. and Woodley, C.M. 1998. Status of shark species. FAO Technical Working Group on the Conservation and Management of Sharks, Tokyo, Japan, 23-27 Apr., 1998, Working Paper, 92 pp, fig. 1-18.

- Castro, J.I., Woodley, C.M. and Brudek, R.L. 1999. A preliminary evaluation of the status of shark species. FAO Fisheries Technical Paper 380. FAO, Rome

- Cadenat, J. and Blache, J. 1981. Requins de Méditerranée et d’ Atlantique (plus particulièrement de la Côte Occidentale d’Afrique). Ed. OSTROM, Faune Tropicale (21).

- Compagno, L.J.V. 1984. Sharks of the World: An Annotated and Illustrated Catalogue of Shark Species Known to Date. Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations. pp. 551–553. ISBN 92-5-101384-5.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. 2008. “Sphyrna tudes” in FishBase. January 2008 version.

- Gallagher, E. 2010. Biological Profiles: Smalleye Hammerhead. Florida Museum of Natural History Ichthyology Department. Retrieved on April 23,.

- Lessa, R.; Menni, R.C. & Lucena, F. 1998. Biological observations on Sphyrna lewini and S. tudes (Chondrichthyes, Sphyrnidae) from northern Brazil. Vie et Milieu. 48 (3): 203–213.

- McEachran, J.D. & Fechhelm, J.D. 1998. Fishes of the Gulf of Mexico: Myxiniformes to Gasterosteiformes. University of Texas Press. p. 96. ISBN 0-292-75206-7.

- Valenciennes, A. 1822. Sur le sous-genre Marteau, Zygaena. Mem. Mus. Hist. Nat. Paris 9:222–228, pls. 11–12.