Florida is on the front lines of climate change. Rapidly rising seas, soaring temperatures, increasing precipitation and extreme storms all threaten to change the way residents use resources and interact with the environment.

Burning fossil fuels like coal, oil and natural gas to power our cars, homes and businesses releases excess carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, thickening the heat-trapping blanket that surrounds Earth. This rampant carbon dioxide, a greenhouse gas, is warming our atmosphere and oceans at alarming rates. According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, as of 2017, Florida was in third place for the amount of carbon dioxide it emits into the atmosphere, after Texas and California.

Stephen Mulkey, a lecturer at the University of Florida teaching topics like global change sustainability, has been studying the climate for over 30 years. He believes Florida’s approach to addressing climate change leaves much to be desired.

“We’re out of time, we’re out of excuses,” Mulkey said. “We’re a day late and a dollar short, but we really, really need to implement wholesale new programs, and we need to throw big money at this,” Mulkey said.

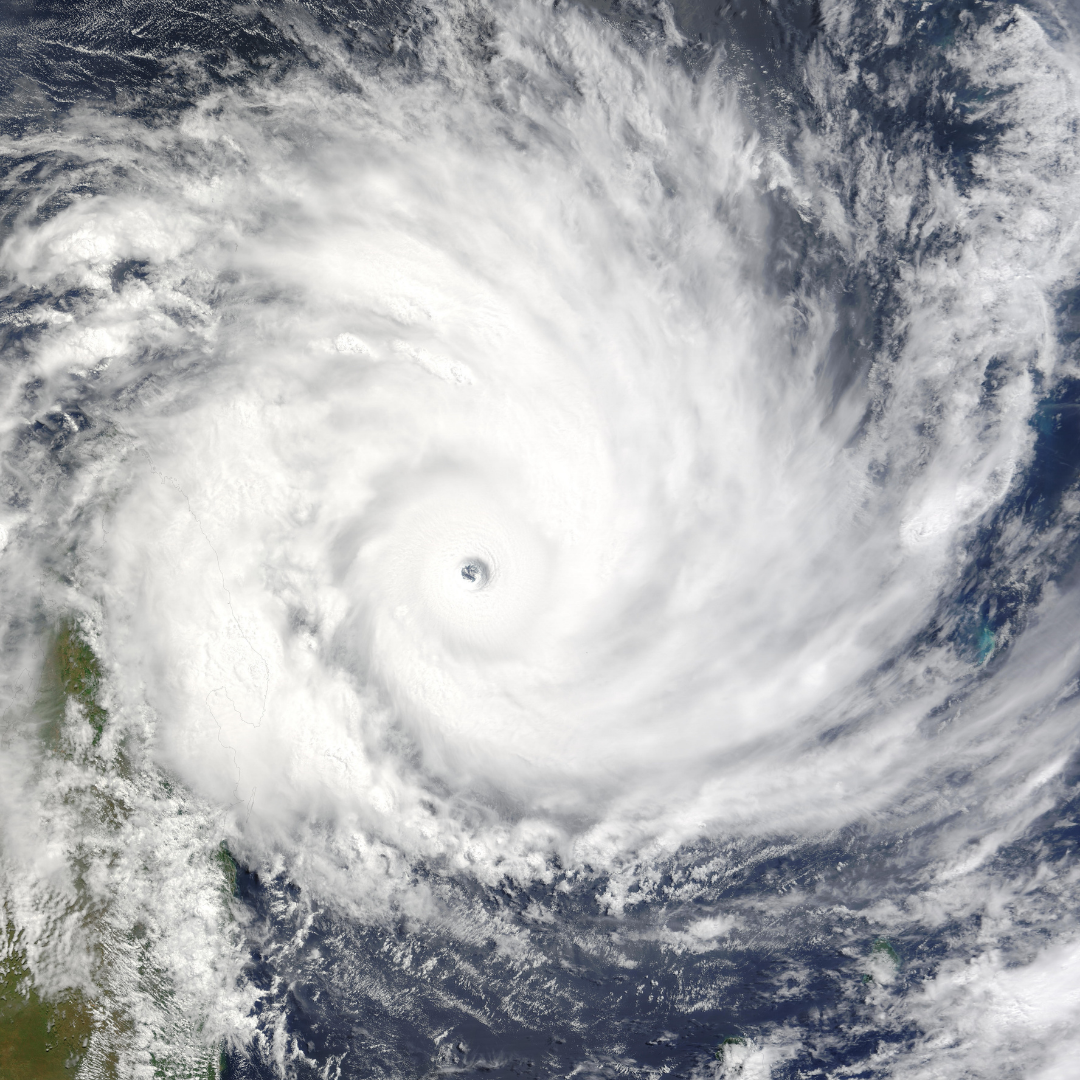

Multiple bills that are related to climate issues are being considered during this year’s state legislative session, addressing topics like greenhouse gases, extreme heat, hurricanes, sea level rise and saltwater intrusion.

Here’s what this year’s climate change legislation is all about:

- Greenhouse Gas Emissions

- Heat Illness Prevention

- Saltwater Intrusion

- Hurricane Loss Mitigation Program

- Statewide Flooding and Sea Level Rise Resilience

- Resilience-Related Advisory Committees

Greenhouse Gas Emissions

Two identical bills, both titled “Greenhouse Gas Emissions,” would preempt, or prohibit, state agencies from adopting or enforcing programs for regulating greenhouse gas emissions without specific legislative authorization. In other words, statewide programs like low carbon fuel standards or greenhouse gas taxes or fees would be prohibited at the state level.

SB 380, proposed by Florida State Sen. Ana Maria Rodriguez (R), and HB 463, proposed by Florida State Rep. Adam Botana (R) and Rep. Lauren Melo (R), define greenhouse gases as carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide, sulfur hexafluoride, hydrofluorocarbon and perfluorocarbon.

Similar bills were proposed in the 2021 legislative session, but both died in committees. These past proposals were seen by some as “symbol bills” meant to draw attention and discussion toward what should be done about regulating these emissions at the state level.

The Center for Climate and Energy Solutions projected that by 2025, U.S. emissions could be 14% to 18% below 2005 levels, which it calls “far short of what is needed to address climate change.” Currently, 24 states have greenhouse gas emissions targets established; Florida does not.

UPDATE: SB 380 died in Environment and Natural Resources; HB 463 died in Environment, Agriculture & Flooding Subcommittee.

Heat Illness Prevention in Outdoor Environment Industries

According to the Union of Concerned Scientists, 32 million outdoor workers are currently employed in the United States. These workers have up to “35 times the risk of dying from heat exposure than does the general population.”

As climate change causes increasing temperatures in Florida, the average number of days of extreme heat (when temperatures reach 103 degrees Fahrenheit or more) is predicted to rise from 25 to 130 each year. Extreme heat could cost the state more than $8 billion in lost productivity, with workers potentially losing 33 days per year due to these intense conditions.

Two identical bills proposed this session, titled “Heat Illness Prevention in Outdoor Environment Industries” and “Heat Illness Prevention,” would require certain employers to provide drinking water, shade, and annual training to employees and supervisors.

HB 887, proposed by Florida State Reps. Kevin Chambliss (D) and Jim Mooney (R), and SB 732, proposed by Florida State Sen. Ana Maria Rodriguez (R), would apply to those in industries like agriculture, construction and landscaping.

According to Nezahualcoyotl Xiuhtecutli, the general coordinator for the Farmworker Association of Florida — which collaborates with research institutions to study farmworker health — intense heat can cause both short- and long-term problems that include dehydration, hypertension, kidney injury, heat stroke or even death.

No penalties would be imposed if the proposed rules are not followed, he said. Instead, these bills are meant to educate people about the dangers of heat on health.

“It has no enforcement mechanism,” he said. “It’s really more about awareness and education.”

A similar heat illness prevention bill was proposed in 2019, but it died in committee. However, Xiuhtecutli is hopeful for success this year because the Senate bill has already passed unanimously in the Senate Agriculture Committee.

“This is farther along than we’ve ever gotten,” he said. “It really is something that should be seriously considered. This bill has offered the opportunity for the state to give more vulnerable groups protections that have real life and death consequences for them.”

UPDATE: HB 887 died in Regulatory Reform Subcommittee; SB 732 died in Health Policy.

Saltwater Intrusion Vulnerability Assessments

Two similar bills proposed this session, titled “Saltwater Intrusion Vulnerability Assessments,” would require coastal counties to conduct vulnerability assessments analyzing the effects of saltwater intrusion on their water supplies and their preparedness to respond to these threats.

SB 1238, proposed by the Environment and Natural Resources Committee and Florida State Sen. Tina Polsky (D), and HB 1019, proposed by Florida State Rep. Wyman Duggan (R), would also provide grants to these communities, require the FDEP to update the comprehensive statewide flood vulnerability and sea level rise datasets and make information received from the assessments available on its website.

Saltwater intrusion is a phenomenon that occurs when sea level rises and saltwater creeps further and further inland, Mulkey said, potentially contaminating groundwater and Florida’s aquifers, which Florida’s 21 million residents rely on for drinking and other purposes. According to the staff analysis of the bill, saltwater intrusion can be “caused by drilling wells too deep, excessive groundwater pumping, sea level rise, severe drought, and other factors.”

“It turns that fresh, sweet water that we’re pumping out of wells into brackish water,” Mulkey said.

Residents can’t just drill deeper to find fresh drinking water because the limestone that characterizes Florida’s substrate is porous, he said. Instead, wells must be moved farther and farther inland, increasing costs for consumers.

Saltwater intrusion can also cause flooding and declines in agricultural productivity, and it can degrade wetlands and islands that act as buffers against storms in Florida, according to the staff analysis.

UPDATE: SB 1238 died in Governmental Oversight and Accountability; HB 1019 died in Environment, Agriculture & Flooding Subcommittee.

Hurricane Loss Mitigation Program

Two other similar bills proposed this session would delay the future repeal of Florida’s Hurricane Loss Mitigation Program and revise the way certain funds in the Florida Hurricane Catastrophe Fund are used.

HB 837, introduced by the Insurance & Banking Subcommittee and Florida State Rep. Matt Willhite (D), and SB 578, introduced by the Community Affairs and Banking and Insurance Committees and Florida State Sen. Ed Hooper (R), would also change the entity that oversees the Manufactured Housing and Mobile Home Mitigation and Enhancement Program from Tallahassee Community College to Gulf Coast State College.

Florida’s Hurricane Loss Mitigation Program is housed in the Division of Emergency Management. It is intended to help Floridians be more prepared for storms and minimize costly hurricane damage.

After Hurricane Andrew slammed South Florida in 1992, the Florida Legislature established a series of programs to help stabilize the state’s economy and insurance industry. One of these programs was the Florida Hurricane Catastrophe Fund, a mandatory reinsurance fund that reimburses residential property insurers after a storm.

Since 1999, the investment income from the Florida Hurricane Catastrophe Fund has provided the Hurricane Loss Mitigation Program with $10 million each year to go toward retrofitting existing public structures, tying down mobile homes, conducting research on hurricane loss reduction and providing grant funding for organizations to improve the resiliency of structures within their communities, according to the program’s 2020 annual report.

UPDATE: SB 578 was laid on the table, meaning it was set aside and died at the end of the session — however its contents were substituted by CS/CS/HB 837; HB 837 has been enrolled, meaning it has been approved by both the House and Senate and sent to the Governor for approval.

Statewide Flooding and Sea Level Rise Resilience

Two similar bills proposed this session, both titled “Statewide Flooding and Sea Level Rise Resilience,” would establish the Statewide Office of Resiliency within the Executive Office of the Governor and provide for the appointment of a Chief Resilience Officer.

The first Chief Resilience Officer (CRO) was appointed in 2019, and several people have held the position since. Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis appointed Wesley Brooks as the current CRO in November 2021.

Among other things, SB 1940, introduced by the Environment and Natural Resources Committee and Florida State Sen. Jason Brodeur (R), and HB 7053, introduced by the Environment, Agriculture & Flooding Subcommittee and Florida State Rep. Demi Busatta Cabrera (R), would also authorize the State Highway System to develop a resilience plan and require the state to conduct a comprehensive statewide assessment of the specific risks posed by flooding and sea level rise.

Due to climate change, increasing temperatures can cause ocean water to expand and glaciers on Earth’s poles to melt. This leads to rising sea levels in coastal areas, including Florida’s 8,435 miles of coastline.

In his opinion, Mulkey doesn’t feel the bills do enough to properly address the issues facing Florida.

“Basically, what I see in these bills is the continual looking in the rearview mirror,” Mulkey said.

But according to the Senate bill’s staff analysis, DEP and the DOT have pledged to continue to identify risks related to sea level rise, flooding, and storms and develop plans, research, procedures and operations to advance resiliency as outlined in the proposed bills.

UPDATE: SB 1940 was laid on the table, meaning it was set aside and died at the end of the session; HB 7053 has been enrolled, meaning it has been approved by both the House and Senate and sent to the Governor for approval.

Resilience-Related Advisory Committees

Two other identical bills would allow resilience-related advisory committees to conduct public meetings and workshops by means of communications media technology. SB 690, introduced by Florida State Sen. Ana Maria Rodriguez (R), and HB 691, introduced by Florida State Rep. Emily Slosberg-King (D), allows more flexibility for members of these committee members to work together despite the geographic distance between them.

Update: SB 690 died in Government Operations Subcommittee; HB 691 died in Government Operations Subcommittee.