Florida has over 8,400 miles of shoreline facing the Gulf and Atlantic coasts, representing iconic landscapes and driving over $400 billion in the state’s economy from tourism, fishing, and more. Sugar sand beaches, coastal mangrove forests, productive salt marshes, and an ancient coral barrier bank reef are just some of the diverse ecosystems along Florida’s coast. But many of these habitats are at risk from coastal erosion, sea level rise, and other threats that impact wildlife and people alike.

As of August 2024, over 400 of Florida’s 825 miles of sandy beaches and inlet shoreline were designated as critically eroded, which is defined by the Florida Administrative Code 62B-36.002(5) as being “a segment of the shoreline where natural processes or human activity have caused or contributed to erosion and recession of the beach or dune system….”

Florida is also facing drastic sea level rise that is projected to increase by as much as a foot in the next 25 years. This will have lasting impacts on existing and future development on and near the coastline, increase the risk for coastal flooding, and is already leading to saltwater intrusion in Florida’s groundwater, which supplies much of the state’s drinking water.

Bills proposed this legislative session focus on protecting Florida’s natural parks and resources, and creating solutions to climate-driven issues like sea level rise.

Here are some of the bills relating to habitat and biodiversity to keep an eye on:

- Nature-based Methods for Improving Coastal Resilience

- State Land Management

- Trust Fund for Wildlife Management

- Other Bills

Nature-based Methods for Improving Coastal Resilience

Mangroves, oyster reefs, salt marshes, and coral reefs are naturally occurring ecosystems that help prevent coastal erosion and reduce the effects of damaging wave and storm action. Historical degradation of these habitats has left Florida increasingly vulnerable.

Identical bills sponsored by Rep. James Mooney (R) and Sen. Ileana Garcia (R), HB 371 and SB 50, would direct the Florida Flood Hub for Applied Research and Innovation at the University of South Florida to develop coastal resilience design guidelines. Coastal resilience refers to the ability of an area to recover from hazards such as coastal flooding and hurricanes and is becoming increasingly important in seaside Florida communities that are facing the brunt of climate disasters.

The Flood Hub was established in the Florida Statutes with the goal of improving flood forecasting and informing “science-based policy.” Under the proposed legislation, which would go into effect on July 1st of this year, it would also be tasked with evaluating the effectiveness of green and gray infrastructure and developing nature-based solutions to sea level rise and storm surge.

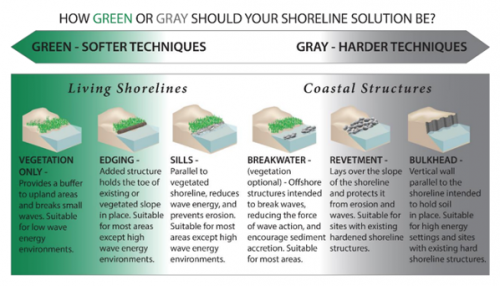

Green infrastructure, such as living shorelines, helps fortify coasts by planting vegetation and restoring oyster reefs. Gray infrastructure creates harder barriers to break wave action, like bulkheads and seawalls.

If these bills were passed, the Flood Hub would be responsible for describing optimal combinations of these infrastructure types and modeling their effects. They would submit a report within a year outlining their recommended designs and standards.

The bills also require the Florida Department of Environmental Protection (FDEP) to publish guidelines on its website “governing nature-based methods for improving coastal resilience.” It specifically calls for the use of mangroves and other vegetation as methods of erosion control.

Mangrove forests, covering 600,000 acres in Florida, are key nurseries for fish and invertebrates; significant carbon sinks; rookeries for nesting seabirds; and coastal shields against storms. The proposed legislation would encourage local governments to participate in the restoration of mangroves and other significant ecosystems like oyster reefs, salt marshes, and coral reefs.

UPDATE: SB 50 died in Messages; HB 371 died on Second Reading Calendar

State Land Management

In August of last year, plans surfaced from the Florida Department of Environmental Protection (FDEP) to develop golf courses, 350-room lodges, pickleball courts, and disc golf courses across nine different state parks. One of the proposals included golf courses on Jonathan Dickinson State Park, which supports critical scrub habitat for the federally threatened and endemic Florida Scrub Jay. The plans, which may have first come into talks with Governor Ron DeSantis’ staff as early as February of 2023, were leaked by a state employee whistleblower and officially unveiled by the FDEP soon after. The public hearings to discuss the plans, as mandated by 253.034 of the Florida Statutes, were scheduled for less than one week after the official announcement.

Following public backlash, the group pushing for the golf courses on Jonathan Dickinson State Park withdrew its proposal. Gov. DeSantis later announced that he did not approve the plans, and the FDEP withdrew the remainder of the projects.

In response to the development plans, Sen. Gayle Harrell (R) filed CS/SB 80, and co-sponsors Rep. John Snyder (R) and Rep. Peggy Gossett-Seidman (R) filed HB 209, similar bills both entitled “State Park Preservation Act.” Both Sen. Harrell’s and Rep. Snyder’s districts include Jonathan Dickinson State Park, which would have been subject to extensive development under the abandoned FDEP plans.

The proposed bills adjust language in the existing Florida Statutes to clarify that state conservation lands “must be managed for conservation-based public outdoor recreational uses; public access…; and scientific research.” They define those “conservation-based public outdoor recreational uses” to include fishing, camping, hiking, nature study, birding, and more, and exclude golf courses, tennis courts, and other sports that require built facilities.

The bills would also state:

- The installation of camping cabins at state parks is allowed, as long as they have a maximum occupancy of six guests. The cabins must be built in areas that minimize the impact to surrounding habitat.

- Any lodging defined in 509.242 of the Florida Statutes is not allowed in the state parks. This includes hotels, motels, vacation rentals, timeshares, and bed and breakfast inns.

- Land management plans on state parks must be made publicly and electronically available at least 30 days before the scheduled public hearing.

- Management plans located within a state park require input from an advisory group.

You can read more about the State Park Preservation Act in our Land Use, Planning and Development section.

UPDATE: CS/SB 80 Laid on Table, refer to HB 209; HB 209 Approved by Governor – Chapter No. 2025-76

Trust Fund for Wildlife Management

HB 843, proposed by Rep. Chad Johnson (R) & Rep. Toby Overdorf (R), and SB 388, proposed by Sen. Ana Rodriguez (R), are similar bills that expand the spending scope of four Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC) Trust Funds.

The FWC is a statewide organization that conducts research, manages resources, enforces rules and regulations, and provides public education all in regard to Florida’s fish and wildlife.

The proposed legislation would amend the following FWC Trust Funds:

- Administrative Trust Fund

Current Uses: A depository to fund management activities across the FWC.

Amendments: Will allow the FWC to invest and reinvest the funds and any accrued interest. Any remaining balance at the end of the year will roll over into subsequent years to be used according to the guidelines of the trust fund.

- Florida Panther Research and Management Trust Fund

Current Uses: To fund Florida panther research, conservation, and protection.

Amendments: Expand uses to include researching and monitoring feline diseases and acquiring lands for panther habitat.

- Grants and Donations Trust Fund

Current Uses: A depository to fund grants and donor agreement activities.

Amendments: Removes the requirement that grant and donor agreement activities must be funded by “restricted contractual revenue.” This will provide greater flexibility in the use of grant and donation funds.

- Nongame Wildlife Trust Fund

Current Uses: Funds population and habitat monitoring, conservation, and public education of Florida nongame wildlife. Allows the FWC to collaborate with other agencies for nongame programs. Nongame wildlife refers to species that are not commonly hunted or fished and therefore do not always benefit from funds collected from licenses and fees associated with consumptive wildlife uses.

Amendments: Expands uses to include law enforcement. Also allows the FWC to collaborate with private landowners on nongame programs.

UPDATE: SB 388 Approved by Governor – Chapter No. 2025-4; HB 209 Laid on Table, refer to SB 388

Other Bills:

- HB 549 and CS/SB 1058 (similar): Gulf of America

- HB 549 enrolled and signed into approval by Governor Desantis – Chapter No. 2025-7

- HB 575 and SB 608 (similar): The Designation of the Gulf of Mexico/ Gulf of America

- HB 575 enrolled and signed into approval by Governor Desantis – Chapter No. 2025-8

- HJR 1625: Appointments to the Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission

- HJR 1625 died in Natural Resources & Disasters Subcommittee