Florida is home to a plethora of migratory species, has more than 80 distinct ecosystems, and belongs to one of the most biodiverse regions in the world. This means that the state often faces unique conservation challenges.

Several bills introduced this session have the potential to affect some of the state’s most-loved species and the habitats they depend on. Measures include enhanced state review of land changes within or near the Everglades Protection Area, establishing rules for mangrove replanting and restoration, developing a Carbon Sequestration Task Force, and designating the American flamingo as Florida’s state bird. Many of these same ideas were proposed last session but died in various committees.

Here’s what this year’s habitats, biodiversity, and conservation legislation is all about:

Everglades Protection Area

The Everglades provides drinking water to more than 8 million people in the state of Florida, supports the state’s $1.2 billion fishing industry, and protects communities from natural disasters like hurricanes and floods. The 18,000-square-mile wetland is also home to over 60 endangered species and is considered the largest surviving subtropical wilderness in the contiguous United States.

The Everglades Protection Area is a large tract of land that encompasses the entirety of Everglades National Park, Arthur R. Marshall Loxahatchee National Wildlife Refuge, and a few other surrounding water conservation areas. This area was designated by the Everglades Forever Act in 1994 and has been the focus of a phosphorus reduction program.

Two similar bills — HB 723, introduced by Florida State Rep. Demi Busatta Cabrera (R), and SB 1364, introduced by Florida State Sen. Alexis Calatayud (R) — would create a two-mile “buffer” zone around the Everglades Protection Area, where small scale development would be prohibited. The bills would also increase the level of review needed for changes to comprehensive plans on land within the protection area or the buffer zone. SB 1364 would also prohibit the adoption of small-scale development amendments for properties located near or within this area.

Rep. Busatta Cabrera told Florida Politics: “Each year, this Legislature allocates funds to protect the Everglades and for Everglades restoration. This will help continue those efforts.”

The Everglades and the surrounding areas are ecologically and economically important for the state of Florida. Setting a higher standard of land development is the main objective in passing this legislation.

Passing the bill will “demonstrate our unwavering commitment to safeguarding the Everglades and ensuring its protection for future generations,” Sen. Calatayud told Florida Politics.

Bills of the same name that aimed to establish the two-mile buffer area and increase the level of review were introduced in the 2022 and 2023 sessions, but died.

UPDATE: HB 723 died in the Agriculture and Natural Resources Appropriations Subcommittee; SB 1364 died in Messages.

Estero Bay Aquatic Preserve

Florida has 42 aquatic preserves that are defined by the Florida Statutes as “state-owned sovereign submerged lands in areas which have exceptional biological, aesthetic, and scientific value, which have been set aside for the benefit of future generations.” Florida’s first aquatic preserve, the Estero Bay Aquatic Preserve, was created in 1966 and expanded in 1983 to cover a total of 13,829 acres and is located on the west coast of Florida, southeast of Fort Myers Beach.

Estero Bay is a lagoonal type of estuary with mangrove forests, seagrass beds, salt marshes, tidal flats, and oyster bars, providing habitat to around 40% of the state’s endangered and threatened species. The bay also indirectly supports commercial and sport fisheries and is an important home for nesting bird colonies.

“Estero Bay Aquatic Preserve is hugely environmentally significant as well as symbolically significant for this area,” said Matt DePaolis, environmental policy director for the Sanibel Captiva Conservation Foundation (SCCF).

“It’s a great example of a healthy place that functions as a nursery for a lot of juvenile species. We have a tourism-based economy, and our water quality and the health of our environment is so closely tied to how we function as a community down here.”

SB 1210, introduced by Florida State Sen. Jonathan Martin (R), would reduce the boundary of the Estero Bay Aquatic Preserve north and east of the Matanzas Pass Channel, removing the submerged land that contains San Carlos Island and the surrounding waters from the preserve. Florida State Rep. Adam Botana (R) sponsored the identical house bill, HB 957.

This bill has caused apprehension among environmental groups throughout the state. This concern is not only regarding the health of Estero Bay but also the precedent this legislation could set for other aquatic preserves in Florida.

“The concern is that it shouldn’t be easy to change the boundary of an aquatic preserve because a lot went into the design and scientific study as to why they chose that boundary in the first place, including all the management plans that are currently in place,” said Holly Schwartz, SCCF policy associate.

Environmental groups like SCCF are asking for more information and clarification about the reasoning behind the bill. The bill could have been proposed to assist with rebuilding efforts after Hurricane Ian or to allow dredging in the area, but its purpose is still unclear. This confusion dates to November 2023, when a public notice regarding the bill was published with limited details about boundary change.

UPDATE: SB 1210 died in the Rules Committee; HB 957 died in the Water Quality, Supply and Treatment Subcommittee.

Carbon Sequestration

Rising sea levels, changes to extreme weather, ocean acidification, and increasing ocean temperatures are only a few ways climate change affects Florida. Because of this, some lawmakers are seeking ways to help lessen the impacts of climate change.

Florida State Sen. Ana Maria Rodriguez (R) is looking to use Florida’s natural landscape to improve the state’s carbon footprint. If passed, SB 1258 would create the Carbon Sequestration Task Force within the state’s Department of Environmental Protection. HB 1187, introduced by Florida State Rep. Lindsay Cross (D), would do the same.

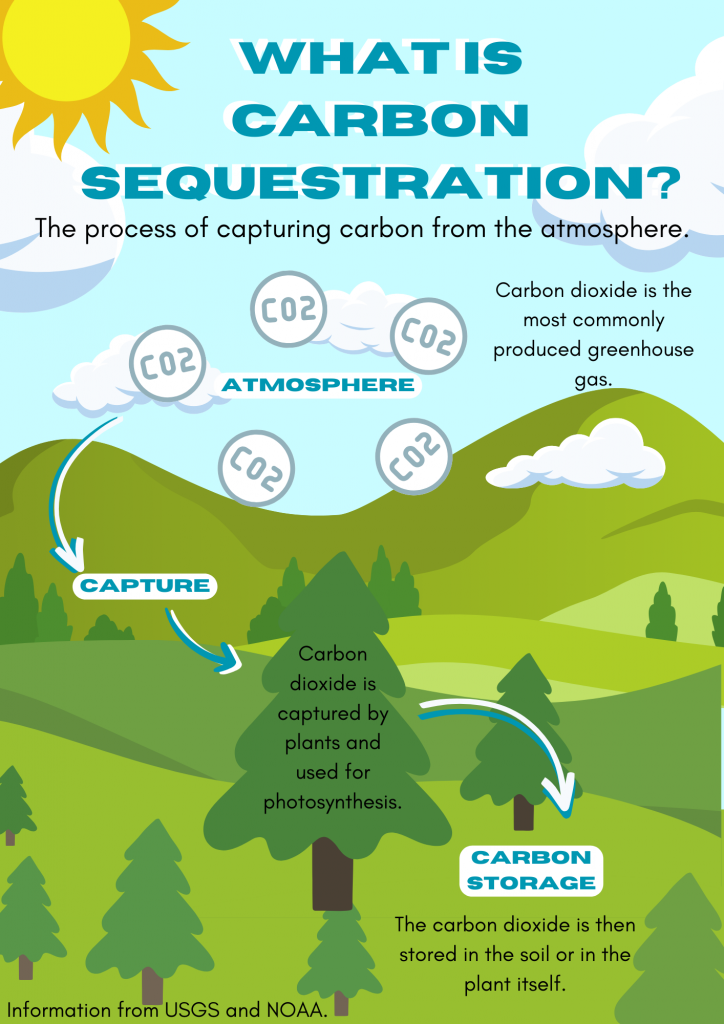

Climate change is caused by the addition of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere that comes from the burning of fossil fuels like coal, oil, and gas to power our homes, transportation, and businesses. The buildup of carbon dioxide acts like a blanket that traps heat around the Earth, which disrupts the climate and leads to impacts such as increasing temperatures and rising sea levels. Carbon sequestration, the process the proposed task force would focus on, traps carbon dioxide, preventing it from contributing to this blanket effect.

“Anytime that we can take carbon out of the atmosphere and lock [it] up somewhere else where it doesn’t return to the atmosphere, that’s carbon sequestration,” Andrew Zimmerman, professor in the UF Department of Geological Science told TESI in 2023.

Carbon sequestration occurs naturally, but the process can also be engineered by humans. Many features of Florida’s agricultural land and natural environment can aid in carbon sequestration. Notably, Florida’s coasts are lined by mangroves, salt marshes, and seagrasses, also known as blue carbon ecosystems, which are very efficient at sequestering carbon.

“With an abundance of land and marine resources, Florida can be a leader in carbon sequestration,” Cross told Florida Politics. “This task force will help us identify how we can optimize carbon storage in our natural and agricultural areas for the benefit of our environment, our economy, and our food systems.”

In addition to establishing the Carbon Sequestration Task Force, the bill would then require the group to identify environments that are suitable for carbon sequestration, consider methods to increase natural carbon sequestration, develop standard methods and metrics to measure success, and identify market opportunities and possible funding mechanisms.

UPDATE: SB 1258 died in the Appropriations Committee on Agriculture, Environment, and General Government; HB 1187 died in the Agriculture and Natural Resources Appropriations Subcommittee.

Mangrove Replanting and Restoration

Florida has an estimated 600,000 acres of mangrove forests that contribute to the overall health and well-being of both the environment and people residing near the coast. In addition to being a sanctuary for threatened and endangered species and providing a nursery for young marine animals, mangroves protect our shorelines from erosion and absorb storm surge impacts from hurricanes.

After Hurricane Ian in 2022, Lee County became visual proof of the services that mangroves provide. Even though the area is still recovering and rebuilding from the disastrous impact of the storm, the mangroves demonstrate evidence of protection.

“All that debris that you see in the mangroves, that’s one boat that was caught by a tree and didn’t go through someone’s house further inland,” said Matt DePaolis, environmental policy director for the Sanibel Captiva Conservation Foundation (SCCF). “That’s visible protection from disruption that is still there.”

Additionally, mangroves and other coastal wetland environments are important for carbon sequestration, which can help mitigate climate change. When mangroves are disturbed or destroyed by human activities like coastal development, carbon is released into the atmosphere.

“Any carbon sequestration we can preserve is a good thing,” Holly Schwartz, SCCF policy associate said. “Mangroves provide better carbon sequestration than some of the other trees inland.”

Currently, mangroves in Florida are protected under the 1996 Mangrove Trimming and Preservation Act, which requires a permit from the Florida Department of Environmental Protection to alter or trim mangroves.

Two identical bills, SB 32 and HB 1581, introduced by Florida State Sen. Ileana Garcia (R) and Florida State Rep. Jim Mooney (R), would require the Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) to adopt rules for mangrove replanting and restoration.

These rules will address erosion in areas of critical state concern, protect barrier and spoil islands, assist in Everglades restoration and Biscayne Bay revitalization, promote public awareness of the value of mangroves, and encourage local governments to create mangrove protection zones.

This legislation was introduced in the 2022 and 2023 sessions but died.

UPDATE: SB 32 died in the Rules Committee; HB 1581 died in the Rules Committee.

Taking of Bears

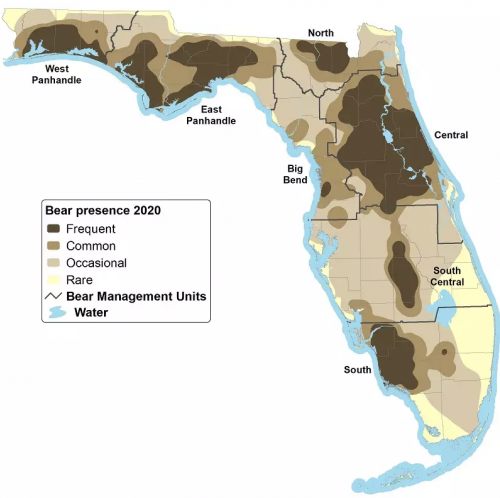

There are an estimated 4,050 black bears distributed throughout Florida. Black bear populations have increased since the 1980s, growing with the population of humans. Because of this, humans and bears are encountering each other more than ever.

Florida State Rep. Jason Shoaf (R), along with multiple cosponsors, has introduced a bill (HB 87) that would allow residents to kill bears on their property without a permit as an act of self-defense. The bill passed in both the state House and Senate. If the bill is signed into law by Gov. Ron Desantis, it will also require that those who shoot the bears cannot sell or possess their carcasses and are required to notify the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC) within 24 hours of the bear being killed.

Florida State Sen. Corey Simon (R), the sponsor of the similar senate bill (SB 632), explained that this bill is necessary to protect citizens from FWC repercussions when they shoot a bear to protect themselves or their property.

“In the event that they [property owners] do have to defend themselves, they risk losing property, risk losing their livelihood,” Simon told WMNF.

Conversely, Florida State Sen. Tina Polsky (D) disagrees with the bill, saying it doesn’t include protections surrounding the use of guns and she’d prefer more focus on securing the trash that attracts bears to residential areas.

“The response is not to create an untenable situation where untrained, unpermitted, more guns in dark places, with potentially children running around, walking down streets, being on a beach, and just shooting bears because you feel threatened,” Polsky told WMNF.

UPDATE: SB 632 was laid on the table, meaning it was set aside and died at the end of the session – however, its companion bill HB 87 was enrolled and sent to Governor DeSantis for approval.

American Flamingo

Florida has many iconic state symbols including, but not limited to, the American alligator (the state reptile), the Florida panther (the state animal), the zebra longwing (the state butterfly), and the sabal palm (the state tree). In fact, Florida even has an official state beverage — orange juice! However, two bills are looking to change one of Florida’s state symbols.

Two identical bills, HB 753, introduced by Florida State Rep. Jim Mooney (R) and Florida State Rep. Linda Chaney (R), and SB 918, introduced by Florida State Sen. Alexis Calatayud (R), would designate the American flamingo as the official state bird. The Northern mockingbird has been Florida’s state bird since 1927 and is also the state bird for Arkansas, Mississippi, Tennessee, and Texas.

The critics of the bill may cite the debate surrounding whether flamingos are native to Florida as a reason they should not represent the state. However, the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission considers the American flamingo a native species under the Federal Migratory Bird Treaty Act. They also state that flamingos were native in the past but disappeared at the beginning of the 20th century, reappearing in South Florida as people started captive colonies of the wading birds.

There has been a history of intense debate over Florida’s state bird. In the past, attempts to declare the Florida scrub jay as the state bird—a species that is only found in Florida—have been met with resistance and were unsuccessful.

UPDATE: SB 918 died in the Fiscal Policy Committee; HB 753 died in the Agriculture, Conservation and Resiliency Subcommittee.

Other Related Bills:

- Shore Protection – HM 1411 (died on the Second Reading Calendar)

- Indian River Lagoon Protection – SB 1354 and HB 1005 (SB 1354 died in the Environment and Natural Resources Committee; HB 1005 died in the Water Quality, Supply and Treatment Subcommittee.)

- Climate Resilience – SB 1630 (died in the Environment and Natural Resources Committee)

- Anchoring Limitation Areas – SB 192 and HB 437 (SB 192 was laid on the table and died at the end of the session – however, its companion bill HB 437 was enrolled and sent to Governor DeSantis for approval.)