This August, Scientist in Every Florida School connected K-5 students in Highlands and Lee counties with UF scientists to help them learn about the nature of science. In the virtual sessions, students were shown how scientists in a wide variety of disciplines use tools such as the scientific method in the course of their research.

In Lee County, fifth graders learned about the process of science from Armando Ubeda, a marine biologist with Florida Sea Grant. Before launching into his example of how the scientific method was used in a red sea urchin case study, he highlighted an even more important message — science is fun! Students learned that science is used in a variety of areas that they may not have thought about — like the ideal time to catch a wave when surfing. Surfers may be able to search online to find out the best times and places for waves, but scientists are the ones who conduct the research that makes it possible.

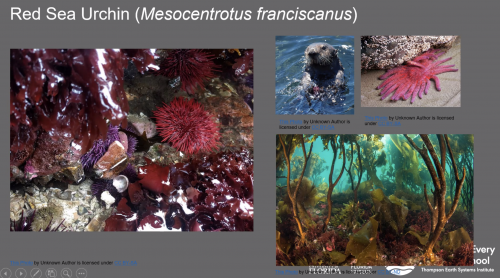

Ubeda then shared one of his own experiences with the process of science. Algae and sea urchins are abundant in the waters along the West Coast of the United States. For years, fishers took the largest adult urchins to sell. Over time, many smaller-sized adult and immature urchins seemed to disappear. At this point, Ubeda came in to find out why using the scientific method. He hypothesized that the smaller urchins needed the larger ones to survive, then worked to verify the hypothesis through a combination of research and fieldwork. The results showed that the hypothesis was correct — smaller urchins used the larger urchins to hide from predators. Thus, even though the fishermen were only taking the larger urchins, all sizes became threatened.

When physical oceanographer Arnoldo Valle-Levinson visited Highlands County first through fifth graders, the first thing he asked them was “What do scientists do?”

Eager students were quick to chime in.

“Discover things on earth and in the water,” said one.

“Ask and answer questions,” said another.

Valle-Levinson agreed that scientists ask a lot of questions, but while they try to answer them, it isn’t necessarily the goal. Often, the results of an experiment will lead to even more questions.

Valle-Levinson also described how he used the scientific method in his work as an oceanographer. He revealed that, while on paper the scientific method can give the impression of solitary researcher following a strict set of steps, in reality, the process is flexible and collaborative.

“We don’t do our discoveries by ourselves,” he told the students. “We do our discoveries with the help of other people.”

The scientific method exists to guide scientists, but not to restrict them. Valle-Levinson explained that sometimes you may skip a step, or take them out of order. Maybe the hypothesis has already been made, or research has already been conducted. Other times, you will follow the method to a T, it all depends on the individual research project. He also stressed the importance of conducting an experiment several times in order to confirm accurate results.

After the presentation, students asked questions about using the scientific method, and about Valle-Levinson’s experiences as a scientist. He explained to them why the pressure of the deep ocean is a roadblock to exploration and discussed his favorite tool — the acoustic doppler current profiler — a device that conducts something similar to a CT (computerized tomography) scan on the ocean.

In a Zoom session with fourth graders, Valle-Levinson led the class through a Google Earth activity to discuss how technology has improved the way that scientists conduct their research. Students were challenged to go out to locations in their local areas and compare their in-person findings to information found on Google Earth. Woodlawn Elementary teacher Toni Cornelius said that they all got a lot out of the presentations. ” The kids loved the meeting and had lots of questions and discussions the rest of the day,” she said.

UF graduate student Rachel Keeffe visited Lee County third through fifth grade classes via Zoom to demonstrate how the scientific method helped scientists learn about the differences between frogs that dig and those that don’t. She stressed that with over 7,000 species of frogs, there is still a lot to learn about the many different species.

“Has anyone done an experiment before?” she asked the class.

Several of the students were excited to answer yes. Keeffe explained how scientists conducted an experiment in which they measured the shapes of different frog arm  bones, separating them into groups of diggers and non-diggers. As the scientists hypothesized, diggers had thicker and shorter bones. Once the results of the experiment are analyzed, scientists consider the conclusions they can draw from the results, and what if anything should be done about it.

bones, separating them into groups of diggers and non-diggers. As the scientists hypothesized, diggers had thicker and shorter bones. Once the results of the experiment are analyzed, scientists consider the conclusions they can draw from the results, and what if anything should be done about it.

“If we find out about how [frogs] live, we can better protect the environment for them,” Keeffe said.

During the Q&A, students were eager to ask questions and share their own experiences with frogs. One student pointed out that they had seen one of the frogs from Keeffe’s slides on the school playground. Other students were curious about how they jump, and the round shape of many frogs’ bodies. The 3rd graders were still bursting with questions when their teacher announced that they had to get ready for their next class.

Keeffe gave them some parting advice, “Go outside and listen for some frogs, it’s one of the best things about Florida I think.”

Are you a K-12 public school teacher in the state of Florida? Request a scientist visit like this to your classroom through Scientist in Every Florida School.

New to our program? Sign up for our monthly newsletter and join our Facebook group!