What are Wetlands?

Wetlands are exactly what they sound like– areas where water covers the soil, at least for a part of the year. There are lots of different kinds of wetlands in Florida, including seasonal or ephemeral wetlands, tidal and coastal marshes, mangrove swamps, and wet prairies. All of these wetlands provide what are known as ecosystem services, which are benefits that humans receive from the environment, whether directly or indirectly.

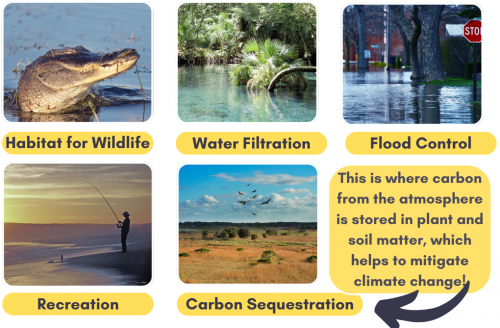

For example, wetlands provide flood protection, water filtration, erosion control, habitat for plants and wildlife, recreation, and carbon sequestration, which is where carbon from the atmosphere is stored in soil and plant matter. And one-third of all endangered or threatened species require wetlands at some point during their life cycle.

The federal Clean Water Act has protected the nation’s surface waters, including wetlands, since 1972. More recently, a Supreme Court decision has limited the scope of the CWA by only including wetlands that have a “continuous surface connection” to protected, permanent bodies like oceans, rivers, and lakes. The decision effectively eliminated protections for isolated and ephemeral wetlands and those with subsurface connections, such as through groundwater.

Florida has state-level protections for wetlands that exceed federal minimums, regulating practices that could impact isolated wetlands or any kind of surface water flow.

What is Wetland Mitigation Banking?

Wetland mitigation banking is a practice that allows land developers to build on protected wetlands by purchasing mitigation “credits.”

Mitigation itself means to compensate for a loss, in this case the damage inflicted upon developed wetlands.

In mitigation banking, the “bank” is the private agency or company that provides the credits, and the “credits” are the mitigation sites.

Mitigation sites are areas where the “bank” is restoring, preserving, or creating a wetland that must be maintained in perpetuity, meaning forever. The sites typically must be located in the same drainage basin as the impacted wetland to reduce negative impacts on the ecosystem.

Much like a property appraisal, each site is evaluated for their individual value to the environment using the Uniform Mitigation Assessment Method (UMAM). The ecological value of the impacted wetland and the anticipated loss are also evaluated, and used to determine the number of credits that a developer has to purchase. The cost for each mitigation credit can be hundreds of thousands of dollars!

Under Chapter 373.4135 of the Florida Statutes, mitigation banks are supposed to “emphasize the restoration and enhancement of degraded ecosystems and the preservation of uplands and wetlands as intact ecosystems rather than alteration of landscapes to create wetlands. This is best accomplished through restoration of ecological communities that were historically present.”

Ideally, mitigation banks work towards fulfilling the “no net loss” policy- which is the idea that any wetlands that are destroyed are fully compensated for with adjoining restoration or preservation projects.

However, mitigation banks do not always achieve these goals, and the value of the mitigation sites often do not fully compensate for the lost wetland ecosystem.

Why It Matters

Florida contains over 20% of the United States’ remaining wetlands, an ecosystem that loses around 60,000 acres annually in the U.S. alone. Wetlands have been drained for agriculture and urban development ever since Florida became a state, leading to the loss of around 10 million acres of Florida wetlands in the last 200 years.

Mitigation banking is considered a compromise between wetland restoration and urbanization, as it allows increased development while maintaining perceived environmental benefits.

But mitigation banks do not necessarily compensate for the total ecological damage caused. A 2007 study done by the Florida Department of Environmental Protection found that sites in mitigation banks that had received “final permit success criteria” still did not achieve full wetland functioning. The approval of credits was more directly tied to specific tasks, such as canal filling, as opposed to the restoration of actual ecosystem functioning. The study also revealed that many mitigation plans failed to consider the details of rebuilding community structure, from groundcover plants to prescribed fire inclusion to wildlife establishment.

Research has also shown that mitigation banking tends to produce large, continuous wetlands rather than small, isolated ones. While large wetlands may be a benefit in terms of preventing habitat fragmentation, they are often less biodiverse than small wetlands and provide an entirely different ecosystem function. When small, isolated wetlands are consolidated through the process of mitigation banking, amphibians and other animals that rely on them for breeding and dispersal are at greater risk of fish predation, and different varieties of wetlands are lost completely.

As Florida’s population continues to grow and its land continues to be developed, there is also an increasing disconnect between the impacted wetland and the mitigation site. A large physical distance between the two means that wetland ecosystem services are entirely redistributed to different populations, potentially altering the natural or historic landscape.

What You Can Do!

Stay informed about mitigation policy and land-use legislation in Florida and contact your legislators to share your thoughts about the importance of wetlands!

There is some legislation currently being proposed in the Florida State Legislature concerning mitigation banking. SB 1646, introduced Florida State Sen. Nick DiCeglie, wants to expand the abilities of mitigation banks in Florida. If the bill is passed, it would allow mitigation credits to be approved in surrounding water basins if there are none available in the same basin as the impacted wetland. This means that mitigation credits would not have to necessarily reflect the same ecosystem as the one that is being destroyed, effectively increasing the disconnect between the impacted wetland and the compensatory one.

Information from Florida Department of Environmental Protection, UF IFAS, National Park Service, Environmental Protection Agency, and National Law Review.