What’s going on?

Whale falls, when a whale passes away and its carcass falls to the seafloor, are part of the natural cycle of life and death. This sudden presence of rich, organic material can feed generations of marine life, leading to a bustling community of fish, scavengers, microorganisms, and more. Think of it as a whale’s final contribution to its underwater home. After decades living as one of the biggest creatures on the planet, its decomposing body then spends nearly the same amount of time– if not longer— silently building an ecosystem that supports a wide diversity of marine life.

But why are whales such unique and important food sources? First, whales are enormous. Blue whales– the biggest of them all– can grow to more than 90 feet long and over 300,000 pounds! That’s as tall as an eight-story building, or as heavy as 30 elephants. Secondly, much of that weight is blubber, which is fat that insulates the whale while it is alive. After death, that fat becomes very desirable cuisine for scavengers!

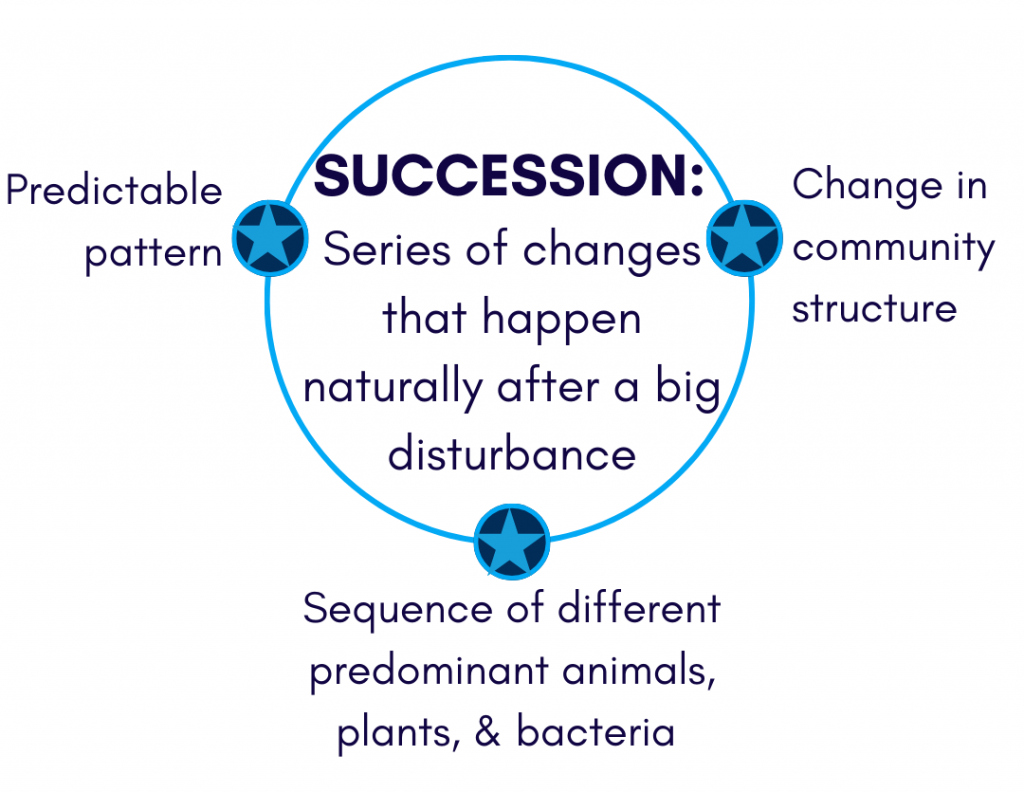

Succession is a series of changes that happen naturally after a big disturbance – like after a forest fire, or a whale fall. It often leads to changes in the community structure, meaning there will be stages where different animals, plants, and bacteria are predominant.

Succession after a whale fall:

- Scavenging is the first step in the “succession” that occurs when a whale falls. In this initial stage, a medley of different animals, including sharks, fish, and invertebrates, arrive to eat the whale’s soft tissue.

- The second step in succession is called the “enrichment-opportunist” stage where organisms colonize the bones and surrounding sediment. These organisms are called heterotrophs because they have to consume other organisms to get energy. Humans are actually heterotrophs! Some of the organisms that eat the whale include polychaetes (which are worms), crustaceans (like crabs), and even bone-eating worms called Osedax.

- The third stage is where it starts to get really interesting. As bones and residual tissue decompose, sulfur and methane are released. These gases are consumed by bacteria and other chemosynthetic organisms. Chemosynthetic creatures create their own energy from chemical reactions in the same way that plants create their own energy from carbon dioxide and sunlight. These bacterial and chemosynthetic communities found in deep-sea whale falls actually resemble communities found in hydrothermal vents or cold seeps. This sulfophilic, or sulfur-loving, stage of whale falls can last for decades!

- The fourth, and final, stage of succession is called the reef stage. At this point the whale skeleton has been reduced to mineral remains, with little to no nutrients and lipids left. The structure is then a home for suspension feeders- creatures that filter their food from the water. This stage may or may not occur depending on the rate of decomposition, and some scientists are still not sure if it is distinctive of whale falls. That just means more ocean exploration needs to be done to find out!

What you can do!

Whale falls are an essential part of ocean ecosystems, providing nutrients and habitat for years to come. Even if you can’t hop in a submarine to the deep sea to observe a whale fall, try to find examples of succession in your own backyard! A fallen tree can be home to hundreds of unexpected organisms. Think of ways that plants and animals, like whales, can provide for the earth long after they’re gone. Even the banana peels in your kitchen can help new things grow! If you want to observe the effects of decomposition in real time, you can start a compost bin and keep a log of the plants, animals, and fungi you spot.

Information from NOAA and:

- Amon, D.J., Glover, A.G., Wiklund, H., Marsh, L., Linse, K., Rogers, A.D., Copley, J.T. (2013). The discovery of a natural whale fall in the Antarctic deep sea. Deep Sea Research Part II: Topical Studies in Oceanography, 92, 87-96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsr2.2013.01.028

- Silva, A.P, Colaço, A., Ravara, A., Jakobsen, J., Jakobsen, K., Cuvelier, D. (2021). The first whale fall on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge: Monitoring a year of succession. Deep Sea Research Part I: Oceanographic Research Papers, 178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsr.2021.103662

- Smith, C.R., Glover, A.G., Treude, T., Higgs, N.D., Amon, D.J. (2015). Whale-Fall Ecosystems: Recent Insights into Ecology, Paleoecology, and Evolution. Annual Review of Marine Science, 7. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-marine-010213-135144

- Smith, C.R. & Baco, A.R. (2003). Ecology of Whale Falls at the Deep-Sea Floor. Oceanography and Marine Biology: an Annual Review, 41, 311-354.