From February 22-23, 2022, over 400 scientists, educators, policymakers, and communicators gathered at the University of Florida Reitz Union for the 8th biennial UF Water Institute Symposium. At this two-day conference, experts shared their research, discussed solutions, and provided wisdom in the midst of Florida’s many water challenges.

The UF Thompson Earth Systems Institute Environmental Leader Fellows, including myself, were given a transformative opportunity to participate in the symposium. For many of us, this was our first-ever in-person conference. I had not stepped foot in the Grand Union Ballroom in the span of two pandemic years. Now, here I was, face-to-face with some of Florida’s leading water experts.

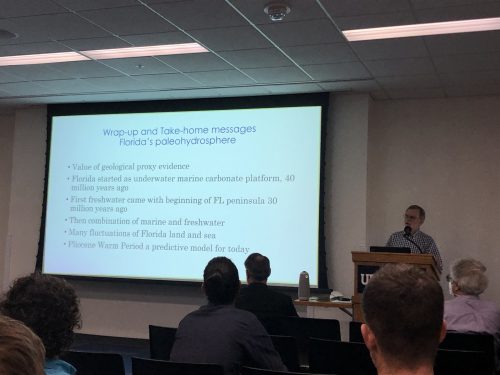

I decided to kick off my day with TESI Director Bruce MacFadden’s presentation titled, “The Geological History of Florida’s Water Over the Past 40 Million Years.”

He explained that by studying the Earth’s rocks, sediments, and glaciers, scientists are able to understand climate conditions over different geological periods. This information also helps us understand how the Floridan aquifer and our many springs, which provide 90% of our state’s drinking water, were formed. Dr. MacFadden also emphasized the ways in which our environment has been impacted during interglacial periods — a warmer period of time between ice ages where glaciers retreat and sea levels rise.

Dr. MacFadden’s panel helped me better grasp why historical and geological research is important in understanding our contemporary water issues. These historical studies help us assess the extent of current sea-level rise and its impact. I was surprised to see the ways in which natural warming during the interglacial period altered the physical environment. With this in mind, Dr. MacFadden cautioned about the alarming rate of sea-level rise during present anthropogenic warming.

When we turn on our tap, we are accessing water from an aquifer that is determined to be between 17,000 and 26,000 years old. By understanding the intricate, interconnected and geological process that has created the Florida aquifer, I felt a greater sense of connection and environmental stewardship.

At the symposium, I also learned that experts and researchers are implementing many different solutions to solve issues surrounding water quality and quantity as well as public health.

I was particularly interested in Dr. Mary Lusk’s research pertaining to the reuse of wastewater. During the panel, Dr. Lusk asked attendees about their perceptions of wastewater; the whole room was divided into a share of groans and enthusiastic nodding. For many, the idea of drinking former wastewater does not seem appetizing. However, Dr. Lusk said that we cannot entirely shut down the idea given our current water shortage.

Yveline Saint Louis, one of the fellows, shared her insight about another panel she attended that discussed current efforts to recharge the Floridan aquifer.

“The most pressing water issue is the depletion of the Floridan Aquifer. The aquifer is one of the most productive in the world and it supplies drinking water to millions of people! It’s a huge deal and is definitely something to rally people over,” Saint Louis said.

“I also learned about the crucial role healthy wetlands play in restoring the aquifer and how we can curb some of the depletion by restoring wetlands. Nature-based solutions are much more effective and are less harmful to ecosystems and habitats.”

The panels that focused on wetland restoration and mitigations include:

- GRU Groundwater Recharge Wetlands

- David Kaplan’s Drivers of Water Balance Variability in the “Ciénega De Las Macanas” Wetland, Panama

- Christopher Keller’s Mcintosh Preserve Wetlands Project – Integrated Water Resources Management for Multiple Benefits

- Scott Knight’s Quantifying the Ancillary Benefits of Constructed Treatment Wetlands

One of the biggest things I learned from the Symposium, and what has been a central theme of this fellowship, is that Florida depends on people from a variety of disciplines to solve its complex water issues: historians, anthropologists, legal scholars, conservationists, resource managers, public health officials, and environmental justice advocates.

Fellow Isabelle Gain shared her experience at a panel she attended on water sovereignty within Navajo Nation.

“The most pressing water issue I learned about is how limited access to running water affected the Navajo Nation during the COVID-19 pandemic,” Gain said. “Professors at Navajo Technical College are working on building transportable water pumps that can be placed on the back of trucks and driven around the Reservation.”

During the symposium, experts stressed that environmental justice is crucial when it comes to solving problems dealing with water quality and accessibility, as many of Florida’s marginalized communities have been impacted.

Gain said she learned that “we can help by advocating for improving infrastructure on Native lands and ensuring that enough funding is being allocated for these purposes.”

To further our engagement in the symposium, fellows were tasked with approaching conference attendees and gathering questions for the final panel “Climate Resilience in a Ground Zero State.” This exercise was a chance to help us break the ice and practice our networking skills.

“Resilience generally refers to the ability to persist or adapt in the wake of disruption. In Florida, climate change is already disrupting local communities, economies, infrastructure, ecosystems, and human health. Indeed, Florida has been described as America’s “ground zero” for climate change. What does climate resilience mean for Florida’s water sector?” the panel overview reads.

The panelists included:

- Beth Lewis from The Nature Conservancy – Florida Chapter

- Carolina Maran from the South Florida Water Management District

- Chris Pettit of the Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services

- Mark Rains from the Florida Department of Environmental Protection

- Jason von Meding from UF’s Florida Institute for Built Environment Resilience.

The closing plenary panel at the 2022 UF Water Institute Symposium focused on Climate Resilience in a Ground Zero State.

I was given the opportunity to ask more about the role and responsibility of corporations when it comes to climate resiliency. Many of the panels emphasized community-based solutions and engagement. However, I pondered the involvement of bigger actors and stakeholders, since many of Florida’s economic sectors such as agriculture and tourism depend on water.

Our panelists presented multifaceted solutions based on corporations taking initiatives to research sustainable opportunities and partner with public sectors and communities. Some of the panelists believed that there needs to be more incentivization and reports to demonstrate the feasibility of solutions.

Von Meding concluded with the belief that “solutions come from a place of care, rather than public image.” Holding corporations accountable and transparent ensures solutions are solely not for public relations purposes, he explained. Instead, solutions serve the best interest of communities and the environment.

After we asked our questions, the panel took questions from the audience.

I was particularly inspired and moved by the sentiments expressed by Joe-Frank from the Seminole Tribe of Florida. He believes much of our issues are deeply rooted in how we view nature as a foe.

Using the Hansel and Gretel analogy, he explained that nature may seem to take the place of the Witch in the scary woods — it riddles us with problems and we may find the best comfort in staying away from it. However, Joe-Frank instead explains that perhaps, in this case, the Witch in Hansel and Gretal was actually a healer. Instead, we must perceive nature and its healing element — in this context, all planetary life is centered around the wellness of water.

At the end of the day, experts such as Joe-Frank, Dr. MacFadden, Dr. Lusk, and individuals from different institutions demonstrate the importance of symposiums and conferences. Such spaces challenge us to think beyond our normative routines and thought processes; they allow for the exchange of ideas, philosophies, and solutions we may have not regarded before. Inclusivity also plays a critical role in ensuring diverse voices are given space to educate and advocate their cause. Perhaps we can even model more events that allow greater public and community participation and engagement.

As for now, I anticipate the next steps that follow in pursuit of Florida’s water solutions.