One of Florida’s most valuable resources is its water. The state is rich in freshwater springs and groundwater that flow through its limestone bed; thousands of lakes and rivers; extensive natural filtration systems in the form of wetlands, marshes, and mangroves; and an endless coastline bordering both the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf. But the natural flow, nutrient content, and clarity of these waters are at odds with one of the fastest growing populations in the nation, and the extensive development, urbanization, and waste that come along with it. The 2025 legislative session includes bills that address public health and water safety, wastewater treatment and infrastructure, and the conservation and management of Florida’s water resources.

- The Safe Waterways Act

- Advanced Wastewater Treatment

- Water Management Districts

- Mitigation Banking

- Former Phosphate Mining Lands

- Waste Facilities

- Permits for Drilling, Exploration, and Extraction of Oil and Gas Resources

- One-Water Approach Toward the State’s Water Supply

The Safe Waterways Act

In 2024, a record-breaking 142.9 million visitors came to the Sunshine State, many of whom are drawn to the 825 miles of sandy coastline and year-round warm weather. However, many water bodies in Florida, including beaches, lakes, and rivers, have been routinely found to be contaminated with bacteria that can induce gastrointestinal illnesses, including diarrhea and vomiting. In 2022, a report identified 943 miles of streams, rivers, and springs and 1,741 acres of lakes and reservoirs that were impaired with fecal coliform, E. coli, or Enterococci and overlapped with source waters for community water systems. Bacteria can get into Florida’s waterways a number of different ways. Stormwater runoff, sewage overflows, leaking septic tanks, and manure and fertilizer runoff can all contaminate groundwater and surface waterways.

In 2024, a record-breaking 142.9 million visitors came to the Sunshine State, many of whom are drawn to the 825 miles of sandy coastline and year-round warm weather. However, many water bodies in Florida, including beaches, lakes, and rivers, have been routinely found to be contaminated with bacteria that can induce gastrointestinal illnesses, including diarrhea and vomiting. In 2022, a report identified 943 miles of streams, rivers, and springs and 1,741 acres of lakes and reservoirs that were impaired with fecal coliform, E. coli, or Enterococci and overlapped with source waters for community water systems. Bacteria can get into Florida’s waterways a number of different ways. Stormwater runoff, sewage overflows, leaking septic tanks, and manure and fertilizer runoff can all contaminate groundwater and surface waterways.

The Safe Waterways Act – SB 156 introduced by Sen. Ana Maria Rodriguez (R) and the similar HB 73 introduced by Rep. Gossett-Siedmann (R), transfers bacteriological sampling duties of beach and public bathing spaces from the Department of Health to the Department of Environmental Protection (DEP). This change will allow for the DEP to issue health advisories, beach closures, and signage related to bacteria updates. Communication with the public is important as beachgoers could be at risk of illness due to the presence of harmful fecal bacteria and E. Coli in the water. Currently, while water quality updates are available on the Florida Department of Health’s website, no signage can be seen by visitors to beaches in person. “I don’t know about you, but when I’m going out to the beach in the morning, I don’t necessarily pull up the red tide page before I head out there,” said Matt DePaolis, the policy director for the Sanibel Captiva Conservation Foundation in an article for Gulf Coast News Now.

Last year, a similar bill passed through the House with unanimous support, but it was ultimately vetoed by Gov. DeSantis. Similar bills were also proposed in 2022 and 2023. According to HB 73’s sponsor, Rep Gossett-Siedmann (R), while the bill is mostly the same, she spoke with the Governor’s Office to identify some small changes that may help the bill to pass this year. “Public safety really needs to be addressed,” she said, according to Florida Politics. “But this is not as big, fiscally, as it was previously entertained.”

UPDATE: SB 156 died in Health Policy; HB 73 died in Natural Resources & Disasters Subcommittee

Advanced Wastewater Treatment

In Florida, waterbodies are considered impaired by the DEP, and added to the “303 (d) list,” when they do not conform to the water quality standards set by the Clean Water Act and federal regulations.

Impairment can result from a combination of factors. Ashley Smyth, a University of Florida assistant professor in biogeochemistry researching the transport of nutrients in coastal ecosystems, described how sewage disposal facilities can contribute to impairment status.

“There are point-sources and non-point sources of pollution. [Non-point] is runoff that captures everything across the landscape where you can’t pinpoint the source. A point-source is a pipe, or something that you can point to. A wastewater treatment plant is a common point-source,” Smyth said in a 2024 interview with TESI.

In 2024, Hurricane Helene caused 6.5 million gallons of wastewater to spill into the Hillsborough River, and Hurricane Milton caused 5.9 million gallons of wastewater to spill from 55 manholes across the city of St. Petersburg, among many other smaller spills. These spills flooded Floridian’s homes and caused a red-tide event to spread across 200 miles of Florida’s coastline.

The Advanced Wastewater Treatment Bill, SB 978, introduced by Sen. Lori Berman (D) and the similar bill HB 861 introduced by Rep. Lindsay Cross (D) propose increased consultation of water management districts and sewage disposal facilities. This legislation highlights the risks of regulatory issues within wastewater treatment. As a proactive measure, this bill aims to mitigate those risks by ensuring that wastewater treatment facilities and sewage disposal facilities continue to upkeep their machinery and facilities. Issues resulting from this upkeep could have significant environmental and human health implications. Rep. Cross told Fox 13 that some of the pipes and facilities in Florida are over 100 years old. “We don’t want to be dumping raw sewage into our beautiful, pristine water bodies, affecting human health, and impacting our economic viability,” she said.

Additionally, the bill would:

- Require the Commission on Ethics to investigate and provide the Governor with a report on any lobbyist or principal who has made a prohibited expenditure.

- Require the South Florida Water Management District, in cooperation with the Department of Environmental Protection, to provide a detailed report that includes the total estimated remaining cost of implementation of the Everglades restoration comprehensive plan and the status of all performance indicators.

- Authorize the districts to levy ad valorem taxes on property by resolution adopted by a majority vote of the governing board, etc.

Last year, the similar bills SB 1304 died in the Environmental and Natural Resources committee and HB 1153 died within the Water Quality, Supply and Treatment Subcommittee.

UPDATE: SB 978 died in Fiscal Policy; HB 861 died in Natural Resources & Disasters Subcommittee

Water Management Districts

There are currently five water management districts in Florida, each responsible for maintaining the supply and quality of water, flood mitigation, and natural system protection and evaluation. This year, the preliminary budget for each of these districts totals over $2.2 billion. The South Florida Water Management District makes up $1.5 billion of this budget request, as their district comprises the Everglades and its restoration.

The Water Management Districts Bill, SB 7002, introduced by Sen. Jason Brodeur (R) and the similar bill HB 1169 introduced by Rep. Bill Conerly (R), would increase oversight and accountability regarding water management district spending and expenditures. The bills would increase transparency between district management, the government and the public. SB 7002 has an appropriation of $1.5 billion and would allow legislators to turn down water management projects. It also has the potential to increase collaboration between water managers and lawmakers specifically around the Everglades Restoration initiatives. Proposed by the Committee on Environment and Natural Resources, this bill aims to foster increased environmental conservation around the Everglades and water management, ensuring that projects use their funds correctly and purposefully.

Initially, the Everglades Restoration Plan was expected to take 30 to 40 years to complete. Today, that timeline has expanded to over 50 years. In a media brief put out by Sen. Ben Albritton (R), the 2025-26 budget for Everglades restoration was revealed to total $750 million. According to Sen. Brodeur, “Over the years, local, state, and federal focus increased resources for environmental restoration and in particular, Everglades Restoration. In some cases, that emphasis has unfortunately manifested itself as mission creep, and left too many core operations at risk of failure.”

Critics suggest that this bill could limit the amount of funding the Everglades restoration project will receive. It includes a section on tax increases due to water management district projects, leading some to fear that projects might lose funding as voters choose to keep taxes low. “It is very, very hard to get voter approval for property tax increases,” said Executive Director of Friends of the Everglades, Eve Samples.

UPDATE: SB 7002 died in returning Messages; HB 1169 Laid on Table, refer to SB 7002

Mitigation Banking

Covering over half of Florida, wetlands are a crucial ecosystem that are not only critical habitats for countless Florida native species, but also provide numerous ecosystem services such as nutrient cycling and flooding mitigation. Today only about half of Florida’s original wetlands remain, and those that do face major threats such as urbanization, coastal development, and erosion.

Mitigation banking is a system that is intended to restore, enhance, or protects ecosystems—such as wetlands and preserves—to compensate for environmental damage elsewhere. It is considered a compromise between wetland restoration and urbanization. Organizations known as ‘bankers,’ create and maintain these protected areas, earning credits that they sell to companies whose activities unavoidably impact the environment. By purchasing credits, these companies offset their environmental footprint by ensuring conservation of a comparable area.

Ideally, mitigation banks work towards fulfilling the “no net loss” policy—which is the idea that any wetlands that are destroyed are fully compensated for with adjoining restoration or preservation projects.

However, mitigation banks do not always achieve these goals, and the value of the mitigation sites often do not fully compensate for the lost wetland ecosystem.

The Mitigation Banking Bill, SB 492, proposed by Sen. Stan McClain (R) and a companion bill, HB 1175, proposed by Rep. Wyman Duggan (R), will make amendments to previous laws around mitigation banks which will increase the frequency of updates around projects and credit approval. It will increase the regulations around mitigation banks and the criteria for obtaining a property with the proper permissions.

It includes a section about using credits in cases where shortages exist. According to the official bill analysis, “The bill also allows project applicants to use mitigation credits from outside a mitigation service area when an insufficient number or type of credits are available within the impacted area.” This means that if a project is underway, and the mitigation bank credit, or wetland, has not been built yet, the organization may still purchase a credit, and the wetland will be built in the future.

Critics state that this could cause further degradation of Florida’s wetland ecosystems, as it allows builders to use their credits in different areas of the state despite differences in the types of habitats that are being displaced. “ You want to replace wetlands with the same type that was impacted,” said Audubon Florida executive director Julie Wraithmell in an interview with WLRN. “So the idea is that you’re not developing all of the grassy marshes and replacing them all with Cypress swamps.” This concern is backed up by research which has shown that mitigation banking tends to produce large, continuous wetlands rather than small, isolated ones.

UPDATE: SB 492 Signed by Officers and presented to Governor; HB 1175 Laid on Table, refer to SB 492

Former Phosphate Mining Lands

Covering more than 450,000 acres of land, Florida is home to 28 phosphate mines, 11 of which are active and found mostly in the central Florida area. Florida’s sediment in this area is rich in phosphate because it was deposited by the ocean millions of years ago. According to the United States Geological Survey, Florida accounts for more than 60% of US production of phosphates. Florida is required to restore former mining lands, but while the science is improving, it seems unlikely that these sites can ever be fully restored to their original conditions. According to the EPA, mined phosphate ore contains potentially cancer-causing radioactive elements.

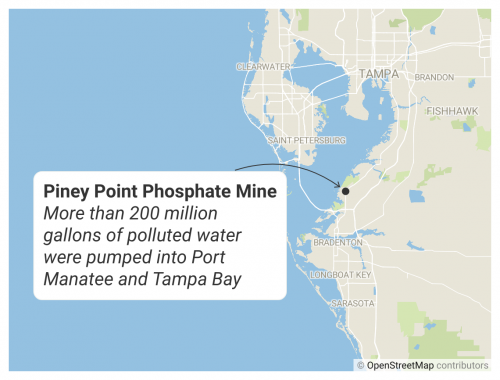

Phosphate is also a major culprit of nutrient pollution. When nutrients such as phosphorous and nitrogen make their way into Florida waterways, they can cause issues such as fish kills, dead zones and algae blooms. In 2021, a wastewater leak at the Piney Point Phosphate Plant caused one of the worst water pollution crises in recent Florida history. Following the spill, Tampa Bay experienced its worst outbreak of red tide in 50 years.

Phosphate is also a major culprit of nutrient pollution. When nutrients such as phosphorous and nitrogen make their way into Florida waterways, they can cause issues such as fish kills, dead zones and algae blooms. In 2021, a wastewater leak at the Piney Point Phosphate Plant caused one of the worst water pollution crises in recent Florida history. Following the spill, Tampa Bay experienced its worst outbreak of red tide in 50 years.

This session, a controversial bill would grant new legal protections to owners of former phosphate mining lands. CS/SB 832, introduced by the Environmental and Natural Resources Subcommittee, the Senate Judiciary and Sen. Danny Burgess (R) and companion bill CS/HB 585 introduced by the Natural Resources & Disasters Subcommittee and Rep. Jon Albert (R), aim to balance the interests of land owners while also taking into account the environmental toll phosphate mining has on Florida’s environment. “This bill provides a new process for landowners of former phosphate mines to record a public notice that their land is a former phosphate mine, and to also have a radiation survey conducted by DOH on their land. If they take both of these steps, that landowner can then assert a much needed and incredibly narrow defense provided by this bill against strict liability lawsuits,” Sen. Burgess said in a statement.

The bill requires the Department of Health (DOH) to conduct surveys of the areas once used for phosphate mining in order to ensure that radiation or environmental contamination is not a threat. A key element of this bill requires the companies operating mining sites to issue radiation levels and ensure that this land is safe for public use. This regulation aims to maintain transparency about the condition of former phosphate mining sites and ensure that public health is not at risk if the land is used for residential development in the future.

Critics of the bill worry that the new bill goes too far to protect owners of former phosphate mines from liability for pollution. They also note that it lacks a specific outline of acceptable radiation levels and does not provide the DOH with an outline of costs for these surveys. This expense could take away from other important projects and DOH activities. But Sen. Burgess and other supporters say that the bill is only focused on a narrow category of lawsuits, especially in comparison to a similar bill that he sponsored in 2024.

UPDATE: CS/SB 832 died in returning Messages; CS/HB 585 died in State Affairs Committee

Waste Facilities

Florida’s Everglades, one of the most ecologically significant and fragile ecosystems in the world, faces ongoing threats from pollution, habitat destruction, and water mismanagement. Waste disposal facilities and water storage infrastructure can contribute to contamination, disrupt natural water flow, and undermine decades of restoration efforts.

In response to these concerns, Florida lawmakers have introduced two bills – SB 946 and HB 1199 – that aim to restrict the construction of waste-related facilities near the Everglades Protection Area and the Everglades Construction Project.

These similar bills, SB 946, sponsored by Sen. Ana Maria Rodriguez (R), and HB 1199, sponsored by Rep. Richard Gentry (R) and Rep. Hillary Cassel (R), propose a ban on the construction of waste facilities within a two-mile radius of these critical conservation areas. The legislation also extends these restrictions to water storage facilities and conveyance structures, ensuring that new developments do not interfere with Everglades restoration efforts or further degrade water quality. By imposing these limitations, the bills seek to prioritize environmental protection, preserve wetland integrity, and safeguard the hydrological balance of the Everglades ecosystem.

As Florida continues to balance development and conservation, SB 946 and HB 1199 represent a proactive effort to shield the Everglades from further environmental strain. With bipartisan sponsorship and growing recognition of the Everglades’ ecological and economic value, these bills aim to ensure the long-term sustainability of this unique and vulnerable ecosystem.

There is also a similar bill – SB 1008 regarding waste incineration around residential areas. These bills aim to protect environmental and community health while outlining areas where these necessary facilities can exist.

UPDATE: SB 946 died in Community Affairs; HB 1199 died in Natural Resources & Disasters Subcommittee

Permits for Drilling, Exploration, and Extraction of Oil and Gas Resources

Oil drilling has profound and far-reaching impacts on local ecosystems, contributing to biodiversity loss, habitat destruction, and the degradation of waterways. The extraction process can lead to soil and water contamination, disrupt wildlife populations, and introduce long-term ecological imbalances. The risks of oil spills, blowouts, and leakage pose significant threats to aquatic and terrestrial habitats, particularly in sensitive environments like Florida’s coastal regions. For a deeper dive into the broader environmental consequences of oil drilling, check out TESI’s previous Tell Me About discussion on the topic.

To address these concerns, Florida lawmakers have introduced HB 1143 and SB 1300, aiming to strengthen environmental regulations on preexisting permits for oil and gas exploration, drilling, and extraction. HB 1143, introduced by Rep. Jason Shoaf (R) and Rep. Allison Tant (D), and SB 1300, introduced by Sen. Corey Simon (R), propose that the Florida Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) adopt stricter environmental review criteria before approving any oil and gas activities. Under these bills, the DEP would be required to assess factors such as the health of local water systems, shoreline stability, and potential risks associated with oil drilling accidents, such as blowouts.

These proposed bills would inhibit oil drilling near Apalachicola Bay to protect the vulnerable aquatic ecosystem near its National Estuarine Research Reserve (NERR). HB 1143 specifies that drilling cannot happen within a 10-mile radius of a NERR, while SB 1300 makes no specifications. Although the bills differ slightly, they both propose a balancing test which must consider the ecological community’s current condition, hydrologic connection, uniqueness, location, fish and wildlife use, time lag, and the potential costs of restoration.

Rep. Shoaf has spoken about the environmental consequences of oil drilling in sensitive coastal areas. “The sea grasses are disappearing, the fish numbers are going down. I’m in the gas business, but at the same time, I represent Apalachicola and Franklin, Wakulla, and Gulf counties. We should not have any drilling near our critical waterways,” he stated. He further clarified his stance, saying, “I am not against oil drilling, I’m just against oil drilling in the Apalachicola basin.”

UPDATE: SB 1300 Laid on Table, refer to HB 1143; HB 1143 Signed by Officers and presented to Governor

One-Water Approach Toward the State’s Water Supply

Florida uses approximately 6.4 billion gallons of water daily, and that number is continuously growing. Water is not an unlimited resource, and with unsustainable water usage, there are projected shortages. Due to this, One Water Florida was created by the Florida Department of Environmental Protection to highlight the benefits of recycled water and show how recycled water could be the change Florida needs to avoid these limitations.

Two similar bills, HR 661, introduced by Rep. Jon Albert (R), and SB 1846, introduced by Sen. Keith Truenow (R), aim to implement a collaborative approach for planning and funding water resource and management projects, to save Florida’s water supply. As Florida’s population grows by approximately 1,000 people per day, the demand on water resources—from household taps and natural streams to aquifers and wastewater systems—increases. This legislation aims to establish a dynamic, integrated approach to managing water projects, ensuring all types of water systems are accounted for.

Despite Florida’s strong water resource protection framework, two-thirds of the state is categorized as a water resource caution area, with over 2,000 bodies of water designated as impaired for water quality assessments. In hopes to mitigate this, the bills, HR 661 and SB 1846, take an integrative approach, or a One Water approach, to prioritize environmental and human health as well as economic sustainability.

Ultimately, HR 661 and SB 1846 seek to ensure the sustainable management of water resources to support the state’s future growth and environmental health and avoid any projected water shortages.

UPDATE: SB 1846 was Adopted, but did not move past the Senate and in-turn died at the end of the session; HB 661 died in State Affairs Committee