So many great questions about sharks! Click below to find the answers:

Approximately 520!

Currently, there are approximately 520 described species of sharks, however, new species are being described all the time. In total, there are around 1,200 species of cartilaginous fishes, which includes the sharks, skates, chimaeras, and rays. For detailed information on individual species, check out our shark species profiles!

Over 400 million years!

Over 400 million years!

Fossil records indicate that ancestors of modern sharks swam the seas over 400 million years ago, making them older than dinosaurs!

Throughout time sharks have changed very little.

Elasmobranchs include sharks, rays, and skates.

Elasmobranchs are a closely related group of fishes, differing from bony fishes by having cartilaginous skeletons and five or more gill slits on each side of the head. In contrast, bony fishes have bony skeletons and a single gill cover.

No, sharks do not have bones.

No, sharks do not have bones.

No, sharks and all other fishes belonging to the class Chondrichthyes that lack true bones. Instead, they have cartilaginous skeletons.

Cartilage is a type of connective tissue strong enough to give support but softer than true bone. Cartilage is found in the human ear and nose. Because cartilage is softer than bone, it is very rare to find complete fossil remains of sharks.

That depends on the shark species.

That depends on the shark species.

While longevity data are not available for many sharks, maximum ages do vary by species.

Some sharks like the smooth dogfish (Mustelus canis) may only live 16 years, while others such as the porbeagle shark (Lamna nasus) may live as long as 46 years. In comparison, Whale sharks (Rhincodon typus), the largest fish in the world, may live over 100 years and the Greenland shark (Somniosus microcephalus) is estimated to live more than 400 years!

Shark skin feels exactly like sandpaper.

Shark skin feels exactly like sandpaper.

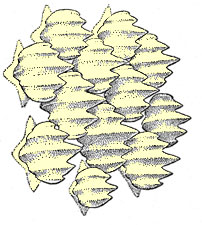

It is made up of tiny teeth-like structures called placoid scales, also known as dermal denticles. These scales point towards the tail and helps to reduce friction from surrounding water when the shark swims.

Because of this, if someone rubbed the skin from the head towards the tail, it would feel very smooth. In the opposite direction it feels very rough like sandpaper.

As the shark grows, the placoid scales do not increase in size. Instead the shark grows more scales. The silky shark (Carcharhinus falciformis) has small scales giving it a “silky” feel to the touch.

That depends on the shark species.

![]() It was once believed that all sharks had to swim constantly in order to breathe and could not sleep for more than a few minutes at a time. Oxygen-rich water flows through the gills during movement allowing the shark to breathe.

It was once believed that all sharks had to swim constantly in order to breathe and could not sleep for more than a few minutes at a time. Oxygen-rich water flows through the gills during movement allowing the shark to breathe.

While some species of sharks do need to swim constantly, this is not true for all sharks. Some sharks such as the nurse shark have spiracles that force water across their gills allowing for stationary rest.

Sharks do not sleep like humans do, but instead have active and restful periods.

Sharks have eyes that are similar to the human eye with some exceptions.

Sharks have the ability to open and close the pupil in response to differing light situations similar to humans while most fish do not possess this ability. A shark’s eye also includes a cornea, iris, lens, and retina. Rods and cones are located in the shark’s retina, allowing the shark to see in differing light situations. Recent work has suggested that most sharks do not see in color.

Sharks have the ability to open and close the pupil in response to differing light situations similar to humans while most fish do not possess this ability. A shark’s eye also includes a cornea, iris, lens, and retina. Rods and cones are located in the shark’s retina, allowing the shark to see in differing light situations. Recent work has suggested that most sharks do not see in color.

In addition, sharks, similar to cats, have a mirror-like layer in the back of the eye referred to as the tapetum lucidum. This layer further increases the intensity of incoming light, enhancing the eye’s sensitivity to light.

Although it was once thought that sharks had very poor vision, we now know that sharks have sharp vision. Research has shown that sharks may be more than 10x as sensitive to light as humans. Scientists also believe that sharks may be far-sighted, able to see better at distance rather than close-up, due to the structure of the eye. Vision varies among species of sharks due to differences in the size, focusing ability, and strength of the eyes.

Yes!

![]() Sharks have an excellent sense of hearing with ears located inside their heads on both sides rather than external ears like humans.

Sharks have an excellent sense of hearing with ears located inside their heads on both sides rather than external ears like humans.

Sharks can hear best at frequencies below 1,000 Hertz which is the range of most natural aquatic sounds. This sense of hearing helps shark locate potential prey swimming and splashing in the water. Sharks also use their lateral line system to pick up vibrations and sounds.

Sharks shed teeth their whole lives.

Sharks have lots of teeth arranged in layers so if any break off, new sharp teeth can immediately take their place. Sharks can shed thousands of teeth during their life, this is why sharks teeth can be found washed onto beaches.

Shark teeth also fossilize easily while the rest of the shark decomposes.

A shark’s coloring helps it hide from predators and prey.

A shark’s coloring helps it hide from predators and prey.

Sharks that swim in open water have a color pattern referred to as “countershading”.

The upper portion of the shark is dark in color to make it difficult to see the shark from above against the dark ocean water. The underside of the shark is light in color so it blends well with the lighter water near the surface when viewed from below. Countershading makes it difficult for predators and prey to see sharks.

In most cases, yes.

In most cases, yes.

Although shark flesh contains high levels of urea and methylamine, any residual toxins that are not washed away when the shark meat is cleaned will quickly dissipate when cooked.

However, sharks may contain high concentrations of heavy metals, primarily in larger, older individuals/species. While many sharks and rays have declined globally, some species have healthy populations and can be sustainably harvested. In many parts of the world shark meat is a staple and important for local communities food security. Shark meat is low fat and provides a good source of protein. Here in Florida, we can often get fresh wild-caught blacktip shark at local grocery stores, which is safe and delicious.

The fastest shark is the shortfin mako (Isurus oxyrinchus).

The shortfin mako has been recorded to reach burst swimming speeds of up to 43 mph (70 km/h). It can chase down some of the fastest fishes such as tuna and swordfish.

The largest shark, and also the largest fish in the ocean is the whale shark (Rhincodon typus). This massive plankton-feeder reaches lengths of over 20m (60 feet).

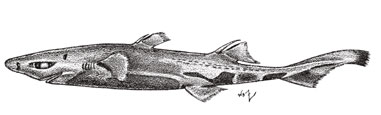

The smallest shark is a deepwater dogfish shark known as the dwarf lanternshark (Etmopterus perryi). This species which is found in the Caribbean Sea is mature at under 20cm (~8 inches).

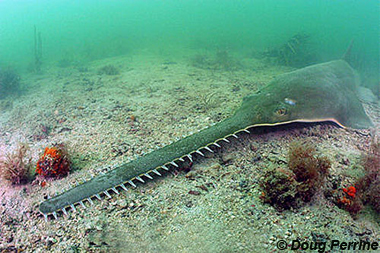

Sawfishes are closely related to sharks, with long, flat, tooth-studded snouts often referred to as “saws”.

Sawfishes found off the coast of the United States are the smalltooth sawfish (Pristis pectinata) and largetooth sawfish (Pristis pristis). Currently, the smalltooth and largetooth sawfishes are listed as a critically endangered species by the World Conservation Union (IUCN) and the U.S. Marine Fisheries Service.

Sawfishes use their rostral saws to hunt with.

They probe muddy or silty bottoms of rivers and shores with their saws in search of marine invertebrates like sea cucumbers, scallops, worms, crayfish, crabs, and shrimp. They can separate their prey from the sand and mud by using the saw as a rake.

The ‘saw’ may also be used by the sawfish as it swims through schools of fish to stun or injure small fishes which it feeds on.

The basking shark is usually seen swimming with its mouth wide open, taking in a continuous flow of water. Food is strained from the water by gill rakers located in the gill slits. The 1000-1300 gill rakers in the basking shark’s mouth can strain up to 2000 tons of water per hour.

Occasionally the basking shark closes its mouth to swallow its prey. These sharks feed along areas that contain high densities of large zooplankton (i.e., small crustaceans, invertebrate larvae, and fish eggs and larvae).

There is a theory that the basking shark feeds on the surface when plankton is abundant, then sheds its gill rakers and hibernates in deeper water during winter. Alternatively, it has been suggested that the basking shark turns to benthic (near bottom) feeding when it loses its gill rakers. It is not known how often it sheds these gill rakers or how rapidly they are replaced.

Hammerheads get their common names from the large hammer-shaped head. This compressed head, also referred to as a cephalophoil, allows for easy distinction from other types of sharks.

Hammerheads get their common names from the large hammer-shaped head. This compressed head, also referred to as a cephalophoil, allows for easy distinction from other types of sharks.

The cephalophoil is broad and flattened, with eyes located on the outer edges of the cephalophoil, and nostrils also spread far apart. It is thought that the head structure may give the shark some sensory advantages. The broad head may be adapted to maximize lateral search area. With an increased distance between the nostrils, hammerheads may be able to better track scent trails.

Along with the pectoral fins, the cephalophoil may provide additional lift and maneuverability as the shark moves through the water. Hammerheads have larger musculature in the head region than other Carcharhiniform sharks and have a wider range of head movement. This allows them increased hydrodynamics and to maneuver quickly at high speeds.

The cookiecutter shark (Isistius brasiliensis) lives in tropical and warm temperate seas throughout the world. It is a small shark, reaching sizes of about 20 inches (50 cm).

This shark’s name comes from the cookiecutter-shaped bites it takes out its victims which includes large fish and whales. A vacuum is created when the cookiecutter shark’s lips attach to the victim. It then takes out an oval-shaped bite of flesh by using its saw-like teeth, leaving behind a cookiecutter-shaped wound.

Different species of sharks have differing maximum depths in which they will travel. Many species are restricted to a small depth range where they are most comfortable. For example, the goblin shark (Mitsukurina owstoni) lives 270-960 m (3150 ft or 0.6 miles) deep. The deepest recorded individual was from 1,300 m (4265 feet or 0.8 miles) deep! Some sharks, like the cookiecutter shark (Isistius brasiliensis), make large vertical migrations. Traveling from 3,281 feet (1000 m) deep to the surface at night to feed.

Most shark species do not breach the water. Of the few that do, 10-15ft is the maximum. White sharks (Carcharodon carcharias) only breach in a limited portion of their total range, though this behavior is often linked with hunting seals. More commonly, smaller sharks in the genus Carcharhinus can be observed jumping 10-20ft while spinning along the US East Coast. There is still some debate if these sharks are blacktips (Carcharhinus limbatus) or spinner sharks (Carcharhinus brevipinna), given how similar the two species appear.