Alopias pelagicus

These sharks are easily recognized for their long upper caudal fin lobes (the top half of their tail fin), which they use to stun smaller fish and squid, making them easier to catch. They are not considered a danger to humans. Historically, they were prized for their large livers, from which squalene oil was extracted to be used in cosmetics, health food, and high-grade machine oil.

Order – Lamniformes

Family – Alopiidae

Genus – Alopias

Species – pelagicus

Common Names

Common names for threshers (Alopias spp.) include such terms as fox shark, fox-shark, foxtail, thresher, thrasher, sickletail, swingletail, and swiveltail. The only other common English name for the pelagic thresher is smalltooth thresher. Other language common names for this species include: cá nhám duôi dài (Vietnamese), hwan-do-sang-o (Korean), kleintand-sambokhaai (Afrikaans), kooseh-e-derazdom (Farsi), nitari (Japanese), pating (Maranao/Samal/Tao Sug), pesce volpe pelagico (Italian), pelagický zralok mlatec (Czech), peagische voshaai (Dutch), quian hai cháng wei sha (Mandarin Chinese), renard pélagique & requin-renard (French), stillehavsraevehaj (Danish), stillahavsrävhaj (Swedish), tubarao-raposo-do-indico (Portuguese), ulappakettuhai (Finnish), and zorro de mar & zorro pelágico (Spanish).

Importance to Humans

Pelagic thresher meat is consumed in many countries, and its fins are used in the Asian shark fin trade. The hide is sometimes made into leather, and liver oil utilized for vitamin extraction. The pelagic thresher contains ten percent of its total body weight as liver weight. The oil from the liver, known as squalene oil, is sometimes used in the manufacture of cosmetics, health foods, and high-grade machine oil. This species is rarely targeted except in the central Pacific and northwestern Indian oceans, but is often caught as a bycatch on floating longline gear set for other sharks, tunas, or swordfish. It is also (rarely) caught in gill nets. Pelagic thresher landings in northeastern Taiwan used to constitute 12% by weight of the total annual shark landings.

All three species of Thresher shark are considered game fish by the International Game Fish Association (IGFA) and are targeted using rod and reel wherever they occur. The largest records having been caught in New Zealand waters, while light-tackle thresher records have been set off California. Threshers, including the pelagic thresher, are eagerly sought after by anglers in Australia, Britain, California, New England (USA), and New Zealand. Famous big-game angler and record holder Zane Grey, writing about the threshers of New Zealand, called these sharks “exceedingly stubborn. Comparing him with the mako, he is pound for pound, a harder fish to whip”.

Danger to Humans

Although this species looks formidable, it is practically harmless and generally avoids divers and swimmers.

Conservation

This species is currently being exploited by directed fisheries (southern California and elsewhere), and is caught accidentally in various floating longline fisheries for tunas and swordfish. Fishing pressure may include being caught in its nursery areas. Fishing pressure combined with its very limited reproductive potential and other life history traits make the pelagic thresher extremely vulnerable. The pelagic thresher probably cannot support intensive exploitation. This species is currently not protected anywhere in the world.

> Check the status of the pelagic thresher at the IUCN website.

The IUCN is a global union of states, governmental agencies, and non-governmental organizations in a partnership that assesses the conservation status of species.

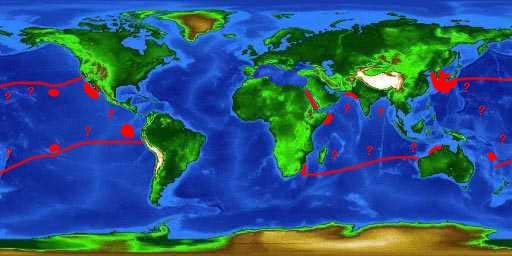

Geographical Distribution

The pelagic thresher occurs in warm and temperate offshore waters of the Pacific and Indian oceans, including the Mediterranean Sea. This species is abundant off the northeastern coast of Taiwan. In North American waters, this species is found off California and Mexico. Distribution data is imprecise due to confusion with the common thresher, and the pelagic thresher may occur over a wider area than is presently known.

Habitat

The pelagic thresher inhabits surface waters of the open ocean, from the surface to at least 150 m (492 ft) deep. It also sometimes occurs in cool inshore waters. It is not known if this species ascends the water column at night, as does the bigeye thresher, Alopias superciliosus. The habitat of this species is poorly known.

Biology

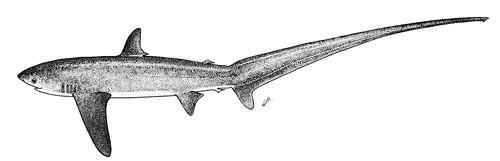

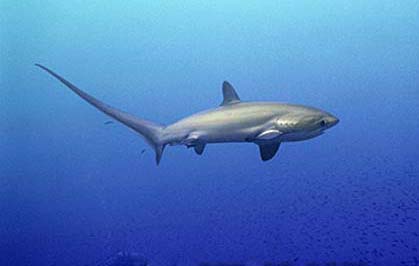

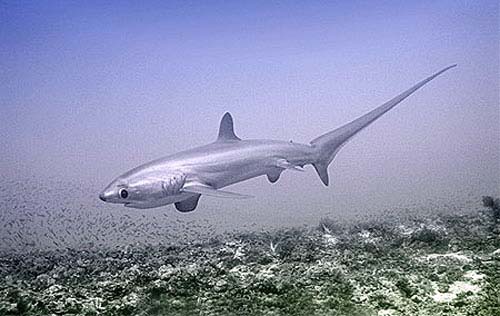

Distinctive Features

All threshers are primarily oceanic sharks with extremely long upper caudal fin lobes. The pelagic thresher closely resembles, and is often confused with, the common thresher but can be distinguished from this species by the presence of dark patches of skin above the pectoral fin bases and by the absence of labial furrows. Common threshers lack lateral cusplets (denticles) on their teeth. The pelagic thresher can be easily distinguished from the bigeye thresher by its smaller eyes and by the absence of deep horizontal grooves along the anterior dorsal surface.

The pelagic thresher is able to elevate its body temperature above that of the water around it by using a special circulatory system. The circulatory system, known as the retia mirabilia, conserves body warmth by routing arterial blood which has been cooled as it passed through gill capillaries, through a network of small arterioles. These small arterioles lay very close to veins containing warm blood draining from organs and tissues. The heat diffuses from venous into the arterial blood and is re-circulated back into tissues and organs. This system allows the pelagic thresher to live in cool water, and allows its muscles to function more efficiently for faster swimming. This advanced heat conserving circulatory system is also used by other lamniforme sharks such as the porbeagle (Lamna nasus), the makos (Isurus spp.), and the white shark (Carcharodon carcharias).

Coloration

The pelagic thresher is lighter in color than the other thresher species. Dorsal surface coloration is blue-gray when alive or very fresh, fading to a pale gray shortly after death. The sides of the body are a light blue-gray (light gray shortly after death), with a white ventral surface. The gill and flank region may have a metallic silvery hue.

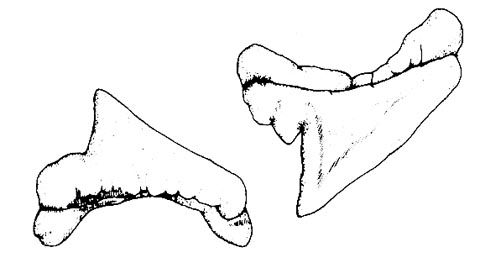

Dentition

The teeth of the pelagic thresher are smooth-edged and very small, having oblique cusps with lateral cusplets on their outside margins. The lateral cusplets are most pronounced in teeth along the upper jaw, and may be difficult to see without magnification. Each tooth root is curved inward. Tooth rows along the upper jaw number 21 to 22 per side, usually without a central (symphysial) tooth row. Lower jaw tooth rows number 21 per side, usually without a central tooth row. There are between 5 and 11 rows of posterior teeth.

Early stage embryos have dentition that is different from that of free-swimming pelagic threshers. Early stage embryos have teeth that are adapted to open ovulated eggs (see Reproduction). Late stage embryos are devoid of teeth, and then grow them shortly before birth.

Dermal Denticles

Pelagic threshers, like all other sharks, are covered in rough, placoid scales known as dermal denticles. Like all thresher species, the pelagic thresher has very small, smooth dermal denticles that have flat crowns and with cusps that contain parallel ridges. Dermal denticles located alongside the body have cusps that point posteriorly.

Size, Age & Growth

The pelagic thresher is the smallest member of the thresher family (Alopiidae). Average size is about 300 cm (10 ft) and 69.5 kg (153.3 lb). This species has been recorded to reach 500 cm (16.4 ft), but this figure is questionable and may have resulted from confusion with other threshers. Most pelagic threshers are less than 330 cm (10.8 ft) and 88.4 kg (194.9 lb). Females measure 282-292 cm (9.2-9.6 ft) at maturity, and are 8.0-9.2 years of age. Males measure 267-276 cm (8.8-9.1 ft) at maturity, and are 7.0-8.0 years of age. The pelagic thresher is known to live up to 16 years in the wild. Extrapolating growth rates for exceptionally large sharks show that large females may be over 28 years old, while large males may be significantly younger (17.5 years). Juvenile pelagic threshers grow faster than do adults. Specifically, this amounts to 9 cm/yr for ages 0-1, 8 cm/yr for ages 2-3, and 6 cm/yr for ages 5-6; versus 4 cm/yr for ages 7-10, 3 cm/yr for ages 10-12, and 2 cm/yr for ages 13 and greater.

Food Habits

Like all the threshers, the pelagic thresher feeds almost exclusively on fishes, especially herrings (Family Clupeidae), flyingfishes (Family Exocoetidae), and mackerals (Family Scombridae). It also feeds on pelagic squids. Feeding is accomplished by using the long strap-like upper caudal fin lobe to stun prey with sharp blows. Threshers are often caught on longlines with their caudal fins snagged on the hook after striking the bait with the upper caudal fin tip. Pelagic threshers, like the other thresher species, sometimes swim in circles around a school of prey, narrowing the radius and tightening the school with their long upper caudal fin lobe. By condensing the school of fishes or squids, the pelagic thresher feeds more easily on its prey.

Reproduction

Development is through aplacental viviparity. This species reaches maturity at a smaller size than other threshers. The smallest mature female recorded measured 264 cm (6.7 ft) in length. Embryos are nourished from the yolk sac in early development but later in development they feed on ovulated eggs (termed ‘oophagy’), with only one young born per uterus. Early stage embryos use their teeth to open ovulated eggs, while later stage embryos swallow the eggs whole. The yolk from the ovulated eggs are stored in the stomach for later processing. This process is known from most species out of the 16 species of lamnoid sharks. There has not been any evidence of intrauterine cannibalism (termed ‘adelphophagy’), such as is found in the sand tiger shark, Carcharias taurus. Brood size is normally two (rarely only one), and young measure between 158 and 190 cm (5.2-6.2 ft) at birth. The sex ratio of young is 1:1. Gravid females in various stages of pregnancy were recorded throughout the year from off northeastern Taiwan. The lengths of the reproductive cycle and the gestation period are presently unknown.

Predators

Predators of the pelagic thresher probably include large predatory fishes (including other sharks) and toothed whales (Cetacea: Odontoceti) inhabiting the same geography and habitat.

Parasites

At least three species of tapeworms are known to inhabit the spiral valve of the pelagic thresher. Litobothrium amplifica, Litobothrium daileyi, and Litobothrium nickoli are internal parasites of the pelagic thresher; the last being a newly described species. These tapeworms were found in pelagic threshers caught in the Gulf of California and the Pacific coast of Mexico.

Taxonomy

The pelagic thresher was first described by the Japanese ichthyologist Hiroshi Nakamura based on three large specimens that measured between 2.9 and 3.3 m (9.4-10.8 ft) in total length. None of these specimens were kept as examples of this species (termed ‘type specimens’), although one of the three sharks and an additional fetal shark (1.0 m, 3.3 ft) was illustrated in Nakamura’s paper entitled On the two species of the thresher shark from Formosan waters, published in August, 1935. Oddly, the fetus that was illustrated may actually be a different species of thresher, the common thresher (Alopias vulpinus), based on the morphology shown in the illustration.

The valid scientific name of the pelagic thresher is Alopias pelagicus Nakamura, 1935. The only other two names for this shark appearing in past scientific literature are Alopias vulpinus Bonnaterre 1788, and Alopias superciliosus Lowe 1841; both are misidentifications of Alopias pelagicus. The generic name Alopias is derived from the Greek word alopexmeaning “fox”. The specific name pelagicus is derived from the Greek word pelagios meaning “of the sea”.

Prepared by: Jason C. Seitz