Carcharodon carcharias

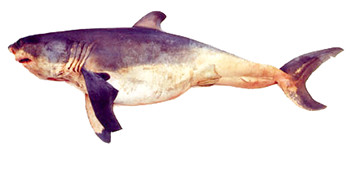

The white shark (or great white) is one of the best known sharks, yet relatively little is known about its biology. It is one of the largest species of sharks, with an estimated maximum size of about 20 feet (600 cm) (Fergusson et al. 2009), though there are unconfirmed reports of white sharks growing to 23 feet (701 cm). White sharks are classically shaped with a triangular dorsal fin, pointed snout and crescent shaped caudal fin. They are identifiable by a sudden color change on their flanks which transitions from greyish-black on top to a very pale, almost white, underside. This species appears intelligent and inquisitive, and exhibits complex social behaviors (Compagno et al. 2005).

Fun Fact: The white shark, along with several other lamniform sharks, is endothermic, or warm-blooded, allowing it to maintain a body temperature that is higher than the surrounding waters (Compagno et al. 2005).

Order – Lamniformes

Family – Lamnidae

Genus – Carcharodon

Species – carcharias

Common Name

The white shark, or “great white”, or “white pointer”, is named for the appearance of dead specimens lying ventral side up, on deck, with their stark white underbelly exposed. Other common English language names are “man eater shark”, and “white death”. Common names in other languages include:

Africaans: Witdoodshaai

Alabnian: Peshkagen njeringrenes

Arabic: Kalb bahr

Finnish: Valkohai

French: Grand requin blanc, Requin blanc

German: Menschenhai, Weißer hai

Greek: Sbrillias

Hawaiian: Niuhi

Italian: Manzo de mar, Squalo bianco

Japanese: Hohojirozame

Maltese: Kelb il – bahar abjad

Norwegian: Hvithai

Polish: Zarlacz ludojad

Portuguese: Anequim

Romanian: Rechin mancator de oameni

Spanish: Tiburón blanco, Jaquentón blanco

Swedish: Vithaj

Importance to Humans

Despite their relative rarity, white sharks are frequently caught by humans. This is due, in part, to the increasing monetary value placed on their jaws and teeth. Entire specimens, some more than 5m long, have been prepared by taxidermist for public display as well as for private trophy collectors. The flesh is often used for human consumption, the skin for leather, the liver for oil, the carcass for fishmeal and the fins for shark-fin soup. Specimens are reported every year in gill nets, trammel nets, herring weirs, purse seines, tuna enclosures as well as on surface hooks, bottom longlines and set-lines (Fergusson et al. 2009).

Danger to Humans

The white shark has been credited with more fatal attacks on humans than any other species of shark. This is due primarily to its size, power and feeding behavior.

View shark attacks by species on a world mapConservation

IUCN Red List Status: Vulnerable

Global population size estimates for this species are unknown. Regional estimates conducted to date are unreliable. It has been proposed that white sharks should be afforded protection because of their position as apex carnivores in the ocean food web. As with most sharks, White sharks are slow-growing producing few young and are therefore highly vulnerable to overfishing. Fortunately, the threat of habitat loss is not significant for white sharks. They are adaptable predators capable of shifting diet as conditions dictate and may simply move away from an area with little food. The most significant challenge for effectively managing white shark populations stems from the lack of accurate data associated with fecundity, age, growth, and population numbers. Given the lack of reliable data, it has been proposed that protective measures be based on the “precautionary principle”, until more biological information has been collected. Research indicates that shark populations, including those of the white shark, will dwindle unless measures for their protection are implemented. Some governments, such as those in South Africa, Australia and the United States, already protect the white shark.

In 2002, the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) placed this shark on its Appendix II list, which demands tighter regulations and requires permits to monitor trade in white shark products (Fergusson et al., 2009).

> Check the status of the white shark at the IUCN website.

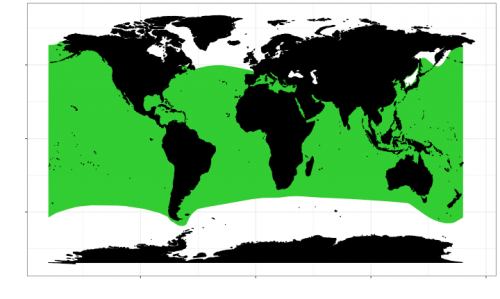

Geographical Distribution

While the white shark is cosmopolitan, it is predominantly found in temperate seas. However, a few large individuals have been recorded in tropical waters. The White shark makes occasional forays into cold, boreal waters and has been recorded off Alaskan and Canadian coasts. It occurs in the western Atlantic from Newfoundland to Florida, the northern Gulf of Mexico, the Bahamas and Cuba as well from Brazil to Argentina, and in the eastern Atlantic from France to South Africa, including the Mediterranean Sea. In the Indian Ocean, it occurs from the Red Sea, to South Africa, the Seychelles, Reunion and Mauritius. In the western Pacific, it ranges from Siberia to New Zealand and the Marshall Islands, off the Hawaiian Islands in the central Pacific and from Alaska to the Gulf of California and Panama to Chile in the eastern Pacific (Fergusson et al. 2009).

Habitat

White sharks spend most of their time in the upper part of the water column in nearshore waters. However, they range from the surfline to the open ocean and from the surface to depths of over 1300 m (4265 ft) (Compagno et al. 2005). White sharks commonly patrol small coastal archipelagos inhabited by seals, sea lions and walruses, offshore reefs, banks and shoals and rocky headlands where deepwater dropoffs come close to the shoreline. White sharks usually cruise in a purposeful manner, either just off the bottom or near the surface, but spend relatively little time at midwater depths.

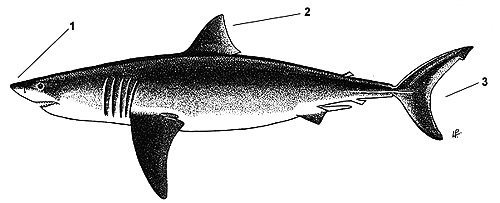

Distinguishing Characteristics

1. Snout is conical

2. First dorsal fin is large and triangular

2. Caudal fin is lunate with a single keel on the caudal peduncle

Biology

Distinctive Features

Body fusiform, snout conical and relatively short, long gill slits not encircling the head. Large first dorsal fin with the origin over pectoral fin inner margins. Second dorsal and anal fins minute. Caudal fin homocercal (crescent shaped), without a secondary keel below extension of caudal keel. Distinctive teeth.

Coloration

Dorsal surface greyish-black, ventral surface pale to white. Boundary between these tones is abrupt. Small, irregular dark spots may be present on the flanks posterior to the last gill slit. Most specimens exhibit a black oval blotch in the axil of the pectoral fin.

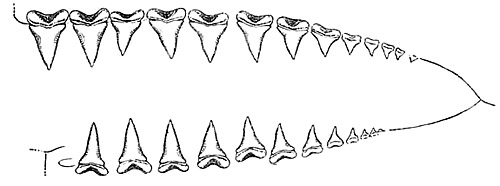

Dentition

Teeth large, erect, triangular and serrated. More slender in lower jaw. In juveniles under 1.8 m (5.5 ft), the teeth have small lateral cusplets and in neonates, the lower teeth may actually lack marginal serration.

Dermal Denticles

Denticles minute, tightly packed with three ridges and very flat blades. Skin of the white shark is relatively smooth in comparison with many other species.

Size, Age, & Growth

The maximum size attained by white sharks is the subject of contentious debate and speculation. Estimates based on modelling (Fergusson et al. 2009) suggest that the maximum total length is about 600 cm (20 ft) and possibly up to 640 cm (21 ft). Males mature at about 350- 410 cm (10- 13 ft) and females at about 450- 500 cm (14- 16 ft). Size at birth is between 109- 165 cm (3.5- 5 ft) (Fergusson et al. 2009). Recent work based on bomb dating suggests that white sharks may live to 70 years or more (Hamady et al. 2014).

Spatial Behavior

Although information about white shark movements are limited, tag-and-release programs in the United States, South Africa and Australia have revealed that the white shark is capable of making movements on localized, regional and intercontinental scales. Generally, larger individuals undertake long journeys across the great ocean basins. Observations of two white sharks cruising in open water, apparently not feeding, revealed a strong tendency to ascend and descend slowly and steadily. The white shark is also capable of short, high-speed pursuits and even launching itself clear from the surface. Patterns in movement and abundance within some areas appear to be linked with seasonal variations in surface temperature. However, this likely has little effect on the distribution of the white shark.

Food Habits

The The white shark is a macropredator, known to be active during the daytime. Its most important prey items are marine mammals including, seals, sea lions, elephant seals, dolphins, and fishes including other sharks and mobulid rays. Marine reptiles (mostly sea turtles) are sporadically ingested. Marine birds and sea otters are inferred to be rejected as prey because these animals are commonly found to have suffered injuries from encounters with white sharks, but are not known to have been ingested.

Predatory behavior is usually divided into five stages; detection, identification, approach, subjugation, and consumption. However, these stages, especially the first and second, are poorly understood in white sharks. The patterns of prey detection and identification in white sharks have been investigated by the use of experimental targets, baits, and other objects in which they are “offered” to the sharks. The results of these experiments reveal that when white sharks have a choice between a square target and a fusiform, seal-shaped target, they select the shape that is more common in their natural environment. Indeed, the choice made in nature is usually whether to respond to a single potential prey item rather than choosing between two of them. When only a single object was presented, it was invariably investigated. Some scientists believe diver and surfer silhouettes, when viewed from below, resemble those of pinnipeds and that this misidentification on behalf of the shark is the cause of most white shark attacks on humans. However, the fact that white sharks attack inanimate objects of a variety of shapes, colors and sizes, none of which resemble those of a marine mammal, are at odds with the commonly asserted hypothesis of “mistaken identity”. Researchers suggest that white sharks often strike unfamiliar objects to determine their potential as food. In this case, it would seem that grasping an unfamiliar object would be the shark’s only reliable method of determining palatability.

Based on underwater observations, scientists have described approach patterns. Most sharks used an “underwater approach” in which they swam just below the surface until they were approximately 1 m (3.3 ft) from the intended prey and then attacked by deflecting the head upward and emerging out of the water. The white shark also presented a “surface-charge” which consisted of a rapid rush with the body partially above the surface. In rare cases, white sharks performed an “inverted approach” in which they swam with the ventral side up. Although the majority of approaches are horizontally oriented, vertical approaches are also common. White sharks readily engage in vertical swimming during feeding activities, sometimes swimming perpendicular to the surface in direct and rapid pursuit of floating objects. There are benefits of using the vertical approach to capture prey positioned near the surface. Firstly, a predator attacking from below is more difficult for the prey to see, while at the same time, the shark has a better view of its prey positioned overhead. In addition, fleeing (rapid movement away from an approaching predator) is probably the most common escape tactic used by animals under attack. Considering these situations, extended escape in the direction opposite the vertically approaching shark is virtually impossible. The propensity for vertical swimming was observed in small white sharks approximately 220 cm (86 in) in length. Scientists believe that the development of this behavior precedes physical changes, such as broadening of the teeth, believed to be adaptations for feeding on large marine mammals.

Few hypotheses about the consumption patterns of white sharks have been made based on observations under natural conditions.

One of these hypotheses, the “bite, spit and wait” theory, is composed of three elements. Initially, the white shark seizes its prey and releases it intact; secondly, the shark waits until the prey lapses into a state of shock or bleeds to death; finally, the white shark returns to feed on the dead or dying animal. However, recent studies do not support this hypothesis. Scientists believe that these sharks may not release potential prey to die but, rather, let them go in response to their defensive behavior or unsuitability as food. Some evidence suggests that white sharks decide a prey’s palatability while it is lodged in the shark’s mouth. Researchers also believe that white sharks may prefer animals rich in energy, such as marine mammals, in favor of less fatty, energy-poor prey. This is supported by some observations of aggregations of white sharks selectively feeding on the blubber but not the muscle layers of mysticete whales. This behavior seems based upon a size-hierarchy, where large sharks dominate in the feeding.

A behavior pattern described as “repetitive aerial gaping” was observed in white sharks of southern Australia. The sharks were seen with their heads out of the water, mouths at or above the surface, rolling onto their side and opening and closing their mouth in a moderately slow, rhythmic, partial gape while swimming slowly along the surface. The most notable difference between this behavior and normal surface feeding is that the repetitive aerial gaping is not oriented toward food or possible targets. White sharks also scavenge from fishermen’s nets and longlines and take all manner of hooked fish. This often results in their own accidental entrapment (Martin et al. 2005).

- Read also: White Shark Feeding Observation

Social Behavior

Some of the white shark’s swimming modes, such as a cautiously timed turn away between two animals on reciprocally approaching one another, is interpreted as conspecific avoidance to maintain individual space. A parallel swimming mode, where two sharks heading in the same direction maintain a fixed distance from each other, also seems to be a way that these animals maintain their personal space. It has been suggested that when two white sharks target the same prey item, they use displays to discourage one another. White sharks have been observed to exhibit “tail slapping” behavior where they use their caudal fin to slap the surface, and to propel water toward a second shark competing for the same resource. They also exhibit other types of display. They have been observed rolling on their sides and directing exaggerated tail beats in one direction, a phenomenon known as “tilting behavior”. Sometimes a white shark will position itself between its intended prey and another shark, preventing the second shark from feeding. White sharks have also been known to propel two-thirds of their body out of the water and land flat against the surface, causing a large splash. This behavior is called a “pattern breach” and may represent a similar, but more intense sign than the tail slap. This specific behavior might also be used to help remove external parasites, attract a mate during courtship or may be the result of a vertical charge approach pattern toward a prey item.

Reproduction

White sharks have viviparous and oophagous reproduction, meaning that embryos hatch in the uteri and are nourished through ingestion of unfertilized eggs until the female gives a live birth (Sato et al., 2016). While in uteri, the embryonic white sharks swallow their own teeth, perhaps to reuse calcium and other minerals. Size at birth ranges from 109- 165 cm (3.5- 5 ft) in total length. Gestation time is unknown but believed to be a year or more with females giving birth every two or three years. Some bite-marks observed on the dorsum, flanks and particularly the pectoral fins of mature female white sharks have been interpreted as mating scars. As in other species of sharks, the male white shark likely grabs the female during copulation. Some records suggest that parturition occurs in temperate shelf waters during the spring to late summer (Fergusson et al. 2009).

Predators

The white shark is an apex predator (atop the food chain) and as such, has very few predators. Killer whales (Orcinus orca) and larger sharks pose the only real threats for an adult white shark. It has been suggested that Killer whales may target white sharks for their fat rich livers.

Parasites of the white shark include thePandarus sinuatus and Pandarus smithii that are often found on the body surface particularly in the axil of the pectoral fins.

Taxonomy and Evolution

The white shark was not always known as Carcharodon carcharias. Since 1758, when it was first named Squalus carcharias, this species has been assigned a variety of scientific names, which have since been synonymized including Carcharias lamnia Rafinesque 1810, Carcharias verus Cloquet 1817, Carcharodon smithii Bonaparte 1838, Carcharodon rondeletii Müller & Henle 1839,Carcharias atwoodi Storer 1848, Carcharias maso Morris 1898, and Carcharodon albimors Whitley 1939. The genus name Carcharodon is derived from the Greek “karcharos” = sharpen and “odous” = teeth. The species name carcharias, also translated from Greek, means point or type of shark, leading to its common name in Australia the “white pointer”.

The relationships between the white shark and the other genera of its family are controversial. Two phyletic arrangements have been proposed. One suggests it is more closely related to the mako sharks (genus Isurus) (figure A), while the other proposes it remains closer to the porbeagle and salmon sharks (genus Lamna) (figure B). Recent studies indicate that the first hypothesis is better. Palaeontological research based primarily on fossil teeth suggests that white sharks and the other genera in the family Lamnidae (Isurus and Lamna) originated in the Paleocene or early Eocene. Fossil registers indicate that, in the late Cretaceous and Paleocene, the lamnid sharks (sharks from the family Lamnidae) were abundant and diverse. The evolution of the white shark also presents various theories. One proposes that it evolved from the megatoothed line of sharks, and another suggests that it evolved from a Miocene mako shark.

References

Cailliet, G.M., Natanson, L.J., Weldon, B.A. and Ebert, D.A. 1985. Preliminary studies on the age and growth of the white shark Carcharodon carcharias, using vertebral bands. Southern California Academy of Sciences, Memoirs 9: 49–60.

Compagno, L., Dando, M., & Fowler, S. (2005). A Field Guide to the Sharks of the World. London: Harper Collins Publishers Ltd.

Fergusson, I., Compagno, L.J.V. & Marks, M. 2009. Carcharodon carcharias. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2009: e.T3855A10133872

Hamady, L.L., Natanson L.J., Skomal G.B. and Thorrold S.R. 2014. Vertebral Bomb Carbon Dating Suggests Extreme Longevity in White Sharks. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0084006

Martin, R.A., Hammerschlag, N., Collier, R.S., Fallows, C. (2005). Predatory behavior of white sharks (Carcharodon carcharias) at Seal Island, South Africa. Journal of Marine Biology Ass. U.K, 85: pp. 1121-1135.

Sato, K., Nakamura, M., Tomita, T., Toda, M., Miyamoto, K., & Nozu, R. (2016). How great white sharks nourish their embryos to a large size: evidence of lipid histotrophy in lamnoid shark reproduction. Biology Open, 5(9), 1211–1215. http://doi.org/10.1242/bio.017939

Revised by Lindsay French and Gavin Naylor 2018

Original preparation by Carol Martins & Craig Knickle