Epaulette Shark

Hemiscyllium ocellatum

This carpet shark is a long, slender shark that tends to be creamy or brown with small dark spots (Compagno 2005). They often forage for food in tidal pools and risk being stranded, but they can survive for up to an hour without any oxygen (Stenslokken et al., 2004) and even “walk” on their fins (Goto et al., 1999) to combat their strandings above the water.

Order – Orectolobiformes

Family – Hemiscylliidae

Genus – Hemiscyllium

Species – ocellatum

Common Names

- English: epaulette shark, blind shark, and itar shark.

- Danish: almindelig epaulethaj.

- Dutch: epaulethaai

- Finnish: lyhtytetra and sokkopartahai.

- French: requin-chabot ocellé.

- Spanish: bamboa ocellada.

Importance to Humans

The epaulette shark is quite docile and easy to approach without risk of injury. Beachcombers can easily catch this species due to its clumsy manner of movement over the bottom substrate and its preference for shallow water habitats. When caught, it will squirm but does not cause any harm to its captors, other than perhaps a nip, and will even approach humans in the reef (Compagno 2002). It is often displayed in public aquarium facilities in the US, Canada, and Australia (Compagno 2002), but is only taken in small numbers and is of no interest to commercial or recreational fisheries at this time (Bennett et al., 2015). However, the population in New Guinea is considered distinct from that of Australia and is threatened by overfishing and habitat destruction (Bennet et al., 2015).

Danger to Humans

The epaulette shark is considered harmless to humans although it may bite if handled (Compagno 2005).

Conservation

> Check the status of the epaulette shark at the IUCN website.

The IUCN is a global union of states, governmental agencies, and non-governmental organizations in a partnership that assesses the conservation status of species.

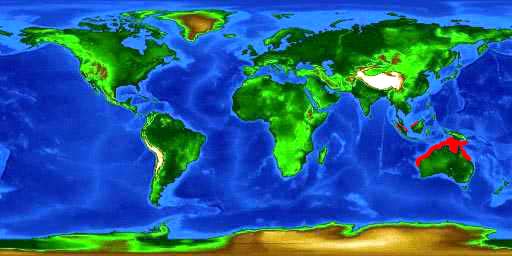

Geographical Distribution

The epaulette shark is found in the western Pacific Ocean in waters around New Guinea and northern Australia (Bennett et al., 2015). Off the eastern coast of Australia, this shark is found as far south as Sydney, New South Wales (Bennett et al., 2015). The epaulette shark may also reside off Malaysia, Sumatra (Indonesia), and the Solomon Islands, however these reports need to be confirmed (Compagno 2005).

Habitat

Commonly found in shallow water coral reef habitats up to 40 m (131 ft.) in depth (Bennett et al., 2015), this bottom-dwelling shark is able to “walk” along the sea floor (Goto et al., 1999). They achieve a crawling-walking motion by bending their bodies while swinging their pelvic and pectoral fins and can apparently maintain this movement over long distances (Goto et al., 1999).

The epaulette shark is also found on reef platforms cut off from the ocean by the receding tide, an environment where the amount of dissolved oxygen temporarily drops to hypoxic levels (Soderstrom et al., 1999). However, the epaulette shark can survive for up to three and a half hours in these conditions (Stenslokken et al., 2004), without a decrease in neurological function (Wise et al., 1998). Adenosine appears to help increase blood supply to the heart and gills playing a role in allowing these sharks to survive in a reduced oxygen environment (Stenslokken 2004). They also appear to use vasodilation to maintain cerebral blood flow (Soderstrom et al., 1999).

Biology

Distinctive Features

The epaulette shark is small, slender and has a short snout. It has an oronasal groove connecting the mouth to the nostrils and small nasal barbels. The two spineless dorsal fins are similar in size and are located posterior of the body. The anal fin is located just anterior to the caudal fin. The precaudal tail is elongated and thick (Compagno 2002). The pectoral and pelvic fins are broadly rounded and paddle-like. Muscular and skeletal modifications not seen in other sharks allow the epaulette to lift its body and move these fins to an approximately 90-degree angle, thus using the fins as ‘feet’ and performing a walking-type motion (Goto et al., 1999).

In Australian waters, the family Hemiscyllidae includes the epaulette shark and the speckled carpet shark (H. trispeculare). The epaulette shark can be distinguished from the speckled carpet shark by the presence of curved dark spots located immediately behind the ocellus of the speckled carpet shark which the epaulette shark lacks (Compagno 2002).

Coloration

The body is cream-colored or brownish with numerous widely spaced small dark spots. There are two large black spots surrounded by a white margin located above the pectoral fins (Compagno 2005). These look like ornamental epaulettes on a military uniform, giving rise to its common name. Juvenile epaulette sharks have several darker brown saddles extending as crossbands on the back and tail, which are lost as they reach maturity, turning into spots instead (Compagno 2002).

Dentition

The teeth are similar in each jaw and are small, broad-based, with a single cusp, directed posteriorly (Allen et al., 2016).

Size, Age, and Growth

The maximum size is 107 cm (42.1 in) total length (Bennett et al., 2015). Males reach maturity at 54 cm (21.3 in) total length while females reach maturity at 62 cm (24.4 in) total length. Initial growth after the young hatch is slow, but after three months epaulettes grow at a rate of around 5 cm per year (Bennett et al., 2015).

Food Habits

The epaulette shark feeds at low tide and is generally most active at dusk and dawn (Compagno 2005). They forage in reef flats (Bennett et al., 2015) and tide pools, potentially using electroreception and olfaction to locate prey (Compagno 2002, Winther-Janson et al., 2012). When foraging the snout is pushed into the sand and the body thrashes to capture hidden prey (Compagno 2002).

Their diet consists of various crustaceans, small fish, and polychaete worms. Adults feed more on crabs and shrimp while juveniles predominantly eat worms and fish, but both utilize suction feeding (Compagno, 2002; Winther-Janson et al., 2012).

Reproduction

The reproductive mode of the epaulette shark is oviparous (Bennett et al., 2015). The female releases paired ellipsoid egg cases under coral heads (Heupel et al 1999) and a can have up to 20 young a year (Bennett et al., 2015). These egg cases measure approximately 9 by 3.5 cm (Heupel et al., 1999) and hatch after about 120 days (Bennett et al., 2015). When the young emerge, they measure approximately 14-16 cm long (5.5-6.3 in) (Bennett et al., 2015).

Predators

Larger fish including other sharks and grouper are predators of the epaulette shark (Harvard, EoL).

Parasites

Parasites include the praniza larvae of gnathiid isopods. The larvae are found primarily near the cloaca and clasper regions as well as in the buccal and brachial cavities. However, it is believed that these parasites cause no harm to the overall health of the host shark (Compagno, 2002).

Several other parasites have been found using epaulette sharks as a host. These include the nematode Proleptus australis (Heupel and Bennett 1998), the crustacean Sheina orri (Bennett et. al. 1997), and myxosporean parasites of the species Kudoa (Heupel and Bennett 1996). The nematodes were primarily found attached to stomach walls, the ostracods in the gill tissues, and the myxosporean in the skeletal muscle fibres. None of these parasites have been shown to have a significant effect on their hosts though.

Taxonomy

Bonnaterre originally described the epaulette shark as Squalus ocellatus in 1788. This name was later changed to the currently valid Hemiscyllium ocellatum (Bonnaterre 1788). The genus name, Hemiscyllium, is derived from the Greek ‘hemi’ meaning half and ‘skylla’ translated as a kind of shark. The epaulette shark is a member of the family Hemiscyllidae, often referred to as the longtail carpet sharks. One synonym, Squalus oculatus Banks & Solander 1827, has appeared in past scientific literature referring to this species.

Revised by: Tyler Bowling and Jennifer Dorrian 2019

Prepared by: Cathleen Bester

References:

- Allen, G.R., Erdmann, M.V., White, W.T. and Dudgeon, C.L., 2016. Review of the bamboo shark genus Hemiscyllium (Orectolobiformes: Hemiscyllidae). Journal of the Ocean Science Foundation, 23, pp.51-97.

- Bennett, M.B., Kyne, P.M. & Heupel, M.R. 2015. Hemiscyllium ocellatum. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2015: e.T41818A68625284. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2015-4.RLTS.T41818A68625284.en.

- Bennett, M.B., Heupel, M.R., Bennett, S.M. and Parker, A.R., 1997. Sheina orri (Myodocopa: Cypridinidae), an ostracod parasitic on the gills of the epaulette shark, Hemiscyllium ocellatum (Elasmobranchii: Hemiscyllidae). International journal for parasitology, 27(3), pp.275-281.

- Compagno, L.J., 2001. Sharks of the world. An annotated and illustrated catalogue of shark species known to date, vol 2. Bullhead, mackerel and carpet sharks (Heterodontiformes, Lamniformes and Orectolobiformes). FAO species catalogue for fishery purposes, 1, pp.viii+-1.

- Compagno, L., Dando, M., & Fowler, S., 2005. A Field Guide to the Sharks of the World. London: Harper Collins Publishers Ltd.

- Goto, Tomoaki, Kiyonori Nishida, and Kazuhiro Nakaya., 1999. “Internal morphology and function of paired fins in the epaulette shark, Hemiscyllium ocellatum.” Ichthyological Research 46, no. 3 : 281-287.

- Harvard OEB 130: Patterns & Processes in Fish Diversity, Encyclopedia of Life. Available from: http://eol.org/pages/208201/details.

- Heupel, M.R., Whittier, J.M. and Bennett, M.B., 1999. Plasma steroid hormone profiles and reproductive biology of the epaulette shark, Hemiscyllium ocellatum. Journal of Experimental Zoology, 284(5), pp.586-594.

- Heupel, M.R. and Bennett, M.B., 1998. Infection of the epaulette shark, Hemiscyllium ocellatum (Bonnaterre), by the nematode parasite Proleptus australis Bayliss (Spirurida: Physalopteridae). Journal of fish diseases, 21(6), pp.407-414.

- Heupel, M.R. and Bennett, M.B., 1996. A myxosporean parasite (Myxosporea: Multivalvulida) in the skeletal muscle of epaulette sharks, Hemiscyllium ocellatum (Bonnaterre), from the Great Barrier Reef. Journal of Fish Diseases, 19(2), pp.189-191.

- Soderstrom, V., Renshaw, G.M. and Nilsson, G.E., 1999. Brain blood flow and blood pressure during hypoxia in the epaulette shark Hemiscyllium ocellatum, a hypoxia-tolerant elasmobranch. Journal of experimental biology, 202(7), pp.829-835.

- Stensløkken, K.O., Sundin, L., Renshaw, G.M. and Nilsson, G.E., 2004. Adenosinergic and cholinergic control mechanisms during hypoxia in the epaulette shark (Hemiscyllium ocellatum), with emphasis on branchial circulation. Journal of experimental biology, 207(25), pp.4451-4461.

- Winther-Janson, M., Wueringer, B.E. and Seymour, J.E., 2012. Electroreceptive and mechanoreceptive anatomical specialisations in the epaulette shark (Hemiscyllium ocellatum). PloS one, 7(11), p.e49857.

- Wise, G., Mulvey, J.M. and Renshaw, G.M., 1998. Hypoxia tolerance in the epaulette shark (Hemiscyllium ocellatum). Journal of Experimental Zoology, 281(1), pp.1-5.