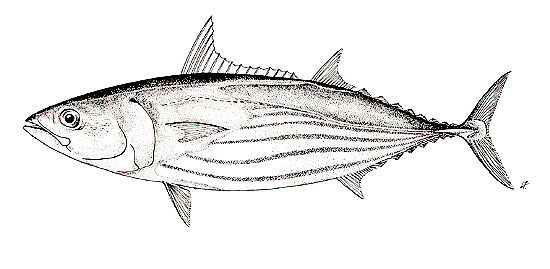

Katsuwonus pelamis

These strong, torpedo-shaped fish are built for speed and agility, with extra finlets and keels, and a forked caudal (tail) fin on a narrow caudal peduncle. Averaging 32 inches long, and 22 pounds, this tuna is a dark blue or purple on top, fading to silver below, and has several dark lines along its sides and belly. One of the most popular tuna fish in the world, skipjack also have a specializes circulatory system that helps conserve heat and makes them somewhat warm-blooded.

Order – Perciformes

Family – Scombridae

Genus – Katsuwonus

Species – pelamis

Common Names

English language common names include skipjack tuna, skipjack, arctic bonito, atlantic bonito, banjo, bonito, lesser tunny, mushmouth, ocean bonito, oceanic skipjack, skipper, skippy, stripe bellied bonito, striped bellied tunny, striped bonito, striped tunny, victor fish, watermelon, and white bonito. Other names used to refer to this fish include aku (Hawaiian), atu (Tahitian), atun (Spanish), balaya (Sinhalese), bonite (French), bonito del sur (Spanish), cachurreta (Spanish), faolua (Samoan), gaiado (Portuguese), jodari (Swahili), listado (Spanish), merma (Spanish), nzirru (Italian), palamatu (Italian), serra (Portuguese), and tunna (Arabic) among many others.

Importance to Humans

In recent decades, skipjacks have come to dominate the world’s tuna market. Major fisheries are based out of Japan, the USA, Indonesia, Papua New Guinea, the Philippines, France, Senegal, and Spain. Commercially, skipjacks are usually taken at the surface, primarily with purse seines. In artisanal industries, hook and line is still a common method of capturing skipjacks. Deeper captures are incidentally made by longline. Many newer practices have made the fishery much more successful in recent years. Artificial flotsam or other manmade floating structures are often used to attract the fish to an area, and aerial spotter planes sometimes accompany fishing vessels. Skipjack is popular in raw fish dishes, where it is marketed as “katsuo”. In Japan it is dried, and known as “katsuobushi”. Skipjack can also be marketed fresh, frozen, or canned.

Conservation

Populations of skipjack tuna in the Atlantic Ocean have declined in recent years while populations in the Pacific Ocean appear to be stable. In the U.S., the National Marine Fisheries Service regulates tuna harvest and tuna imports for compliance with international conservation requirements.

At this time, the skipjack tuna is not listed as threatened or endangered with the World Conservation Union (IUCN) Redlist and is considered to be in no immediate threat. The IUCN is a global union of states, governmental agencies, and non-governmental organizations in a partnership that assesses the conservation status of species.

> Check the status of the skipjack tuna at the IUCN website.

Geographical Distribution

Skipjack tuna are distributed circumtropically. Additionally, they are present along the oceanic coast of Europe and throughout the North Sea, but are absent from the Mediterranean Sea and Black Seas.

Habitat

The skipjack tuna is an epipelagic fish, occurring in waters ranging in temperature from 58-86°F (14.7 to 30°C). While skipjacks remain at the surface during the day, they may descend to depths of 850 feet (260 m) at night. Skipjacks have a tendency to school, often under drifting objects or marine mammals. Skipjacks exhibit many types of schooling behavior, sometimes schooling with drifting objects, sharks, or whales. They may swim slowly in circular paths or travel in a single direction. These schools may consist only of skipjack, or other tuna species may be present. Skipjack often divide into schools based upon their size. This may be because the smaller fish cannot maintain the same top speeds of larger fish. Small fish may school while feeding, whereas larger fish (greater than 8 inches (20 cm)) tend to feed alone.

Biology

Distinctive Features

Like other tunas, the skipjack tuna has a fusiform body shape. It has two dorsal fins: the first with spines, the second without. Following the second dorsal fin are 7 to 9 finlets with separate rays useful in reducing turbulence and maintaining directional control when swimming at high speeds. The anal fin placement begins under the second dorsal fin and is also followed by 7 or 8 finlets. The caudal peduncle has three sets of keels: a large one on the base of the peduncle inserted between two smaller pairs. Keels are ridges that also help the fish maintain its position in the water when moving swiftly. The mouth extends to the center of the eye. The swim bladder is absent. Skipjack have a special system for partially regulating their body temperature, known as counter current exchange. This allows them to conserve body temperature, making them partially “warm blooded.”

Coloration

The body color above is dark blue or purple, while the belly and lower sides are silvery and have 4 to 6 dark but broken lines running the length of the body. These stripes along the belly distinguish this tuna from other scrombrids living in the same waters.

Dentition

There is a single row of small, conical teeth in the mouth.

Size, Age, and Growth

The record maximum length is 43 inches (108 cm) fork length and the maximum weight is 76 pounds (34.5 kg). Skipjack tuna commonly grow to a length of 32 inches (80 cm), and a weight of 7-22 pounds (8 to 10 kg).

Food Habits

Skipjack feed primarily upon fishes, crustaceans, and mollusks. Fishes that are preyed upon by the skipjack tuna include herrings, anchovies, and sardines. Cannibalism is common with this species as well. Their diet appears to be very broad and suggests an opportunistic method of feeding. The peaks of foraging appear to occur around dawn and dusk. This may be in response to the diurnal, vertical migrations of other organisms, or it may suggest that skipjack satiate their food drive mid-day. Additionally, since skipjack appear to rely on vision when feeding, night may not offer enough light for visual recognition of prey. Schools of skipjack are commonly found near convergences and upwellings. In such sites, distinct bodies of water, often of varying temperature, collide with one another. These areas are generally very productive and food is abundant. Other organisms that may compete with adult skipjack for food include the whale shark, yellowfin tuna, albacore, frigate tuna, dolphin fish, rainbow runner, and seabirds.

Reproduction

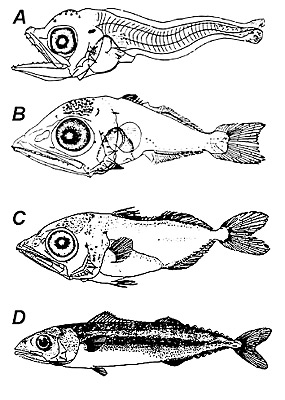

Skipjack are oviparous. In warm equatorial waters, skipjack spawn year-round while further away from the equator, spawning season is limited to the warmer months. Sexual maturity may occur as small as 15 inches (40 cm) length, however most fish appear to mature at larger sizes. Larger females produce significantly more eggs than smaller females, with the average adult producing 80,000 to 2 million eggs per year. The eggs are approximately 0.94 mm in diameter, with a clear shell. The larvae hatch at a size of 3.0 mm. They have large heads and jaws, and lack body pigmentation. They can be distinguished from closely related larvae by their pigmented forebrains. Like Thunnus species, they also lack pigment in the caudal region.

Predators

Large predatory fishes such as sharks, yellowfin tunas, billfishes, and wahoo, as well as seabirds are all predators of the skipjack tuna. Cannibalism is also known to occur in this tuna.

Parasites

A well-studied host, the skipjack tuna has 75 documented parasites. These parasites include digenea (flukes), didymozoidea (tissue flukes), monogenea (gillworms), cestoda (tapeworms), nematoda (roundworms), acanthocephala (spiny-headed worms), and copepods. The cookiecutter shark (Isistius brasiliensis) is also a parasite of the skipjack tuna.

Taxonomy

The skipjack tuna was first described in 1758 by Carl Linnaeus, who named it Scomber pelamis. There is still much debate about the generic placement of the skipjack, some prefer to group it with other members of the genusEuthynnus, while others recommend it be placed in its own genus, Katsuwonus. The species name pelamis is derived from Latin, meaning “tunny”. Other names which have been used to refer to this tuna include Scomber pelamides Lacepede 1880, Scomber pelamys Bloch and Synder 1801, Thynnus pelamys Cuvier 1817, Thynnus vagans Lesson 1826, Orcynus pelamy Poey 1875, and Gymnosarda pelamis Dresslar and Fesler 1889.

Prepared by: Susie Gardieff