Lamna nasus

This shark closely resembles the white and salmon sharks, but it is easy to identify the white or light gray free rear tip of its dorsal fin. It has the classic mackerel shark appearance, from its conical snout to its crescent caudal (tail) fin, and the dark grey coloring over its body except for the pale underside. And like other sharks in its family, it can raise its body temperature almost 20 degrees above surrounding water temperatures. The porbeagle can get as large as 12 feet long and 500 pounds, but is only considered moderately dangerous to humans.

Order – Lamniformes

Family – Lamnidae

Genus – Lamna

Species – nasus

Common Names

The porbeagle belongs to the family Lamnidae, commonly called the mackerel sharks. The name porbeagle is derived from the Cornish “porgh-bugel,” and probably comes from a combination of “porpoise,” referring to its shape, and “beagle,” referring to its hunting prowess.

In French, the porbeagle is known as requin-taupe commun, in Spanish, marrajo sardinero, and in German, Heringshai. Other English language common names include Atlantic mackerel shark, blue dog, bottle-nosed shark, and Beaumaris shark.

Importance to Humans

In the past, when population abundances were higher, porbeagles were often considered a nuisance because of the damage they often caused to light fishing gear. Today, there are regulated Norwegian and Canadian fisheries for porbeagles in the north Atlantic. In the southern hemisphere, there is a small regulated Norwegian fishery. The porbeagle is also a significant bycatch species, the second most common in the Norwegian fishery. It is also commonly caught as bycatch by Japanese longliners and probably other fisheries in the southern Indian Ocean. The catch in these fisheries is probably used mostly for fins.

Harvested porbeagle flesh is used for human consumption. The porbeagle is also used for its oil, to make fishmeal (fertilizer), and its fins are used for shark-fin soup.

The porbeagle is a popular gamefish, although less active than its relatives the shortfin mako and the white shark. There are recreational fisheries in the United Kingdom, Ireland, and the United States, and catch-and-release in Canada.

Danger to Humans

Although the porbeagle is related to the much-feared shortfin mako and white shark, it rarely attacks humans. The International Shark Attack File (ISAF) lists two unprovoked attacks by porbeagles off England and Canada, both on divers and both non-fatal.

Porbeagles have been filmed making fast passes at divers on oil platforms in the North Sea without attacking. This is probably agonistic (defensive) or exploratory behavior.

Conservation

> Check the status of the porbeagle at the IUCN website.

The IUCN is a global union of states, governmental agencies, and non-governmental organizations in a partnership that assesses the conservation status of species.

The porbeagle shark is listed as “Near Threatened” throughout its range and as “Vulnerable” in the northeast Atlantic Ocean where the porbeagle is considered over exploited. In 2000, catch rates of immature porbeagles were about 30% of those in 1991; catch rates of mature porbeagles were about 10% of those in 1992.

Porbeagle stocks in the North Atlantic were seriously depleted due to over fishing in the latter half of the twentieth century. Up until the mid-twentieth century, the porbeagle was intensively fished by Norway, as well as Denmark and Sweden, in European waters. Catches peaked in 1947, and declined steadily thereafter, leading Norway to expand its fishery to the Northwest Atlantic. When stocks there were similarly depleted, the Norwegian fishery shifted to targeting other large pelagic fishes.

Today, the porbeagle is protected in U.S. waters and catches are regulated by the European Community, which permits only a small regulated catch for Norway and New Zealand. Also, since 1995, Canada has limited fishing licenses, gear, fishing areas and seasons for the porbeagle, prohibited finning of porbeagles and limited recreational fishing to catch-and-release only. In 1997, the world catch reported to the FAO was 1736 tonnes, while the current maximum sustainable yield is estimated at 1000 tonnes.

Catches of the porbeagle in the southern Indian Ocean are little reported and poorly known. It is a significant bycatch species of Japanese longline fisheries and probably others. There is no regulation on catches of the porbeagle in the southern hemisphere, except for the New Zealand fishery.

Geographical Distribution

In the northern hemisphere, it is found only in the Atlantic Ocean. This is an important trait that distinguishes it from its close relative, the salmon shark (Lamna ditropis), which only inhabits the northern Pacific Ocean. In the northern Atlantic, the western boundary of the porbeagle’s range is the northwest coast of North America, from New Jersey (and possibly South Carolina) to Canada and Greenland. The eastern portion of its north Atlantic range includes the northwest coast of Africa and the Mediterranean, and proceeds up to waters off Iceland to the north coasts of Norway and Sweden and the northwest coast of Russia. In the southern hemisphere, the porbeagle’s distribution is circumglobal, in a band from 30o to 60oS.

There is apparently little exchange between porbeagle populations. For example, populations of the northwest Atlantic seem relatively segregated from those of the northeast, and populations in the northern hemisphere are separate from those in the southern hemisphere.

Habitat

Although the porbeagle is predominantly pelagic (open-ocean), it can be found in both coastal and oceanic waters. The species occurs in both hemispheres and is found at water temperatures from 34o to 64oF (1o-18oC). It prefers cold water, but was once recorded in water of 73oF (23oC). It does not appear to enter freshwater, but has been caught in a brackish estuary of Argentina. It can be found at the surface to a depth of 2,346 ft (715 m).

Like other large pelagic sharks, the porbeagle undertakes extensive seasonal migrations. In this species, these migrations appear to be largely longitudinal and are probably temperature-related.

Porbeagles appear to segregate by both size and sex. Skewed sex ratios are often noted in catches of this species. Also, in catches in the Bristol Channel, large females were notably absent, meaning mature females may separate from mature males and juveniles for some part of the breeding cycle. This phenomenon has been reported for other pelagic sharks, such as the salmon shark, Lamna ditropis (the porbeagle’s Pacific congener), and the blue shark, Prionace glauca, and may be advantageous in limiting copulation to a specific season as well as preventing cannibalism of neonates by adult males.

Distinguishing Characteristics

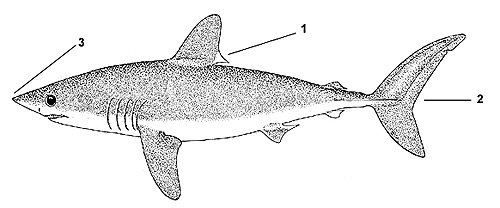

1. First dorsal fin has a white patch on the trailing edge

2. Caudal fin is lunate with two keels

3. Snout is conical

Biology

Distinctive Features

The porbeagle has a heavy spindle-shaped body with a moderately long conical snout. The gill slits are large. The caudal peduncle is strongly keeled, with short secondary keels on the caudal base. The caudal fin is crescent-shaped. The large first dorsal fin has a white free rear tip. The second dorsal and anal fins can pivot.

In addition to having different ranges, the porbeagle can be distinguished from its congener the salmon shark by its slightly longer, more pointed snout. This characteristic also differentiates it from the white shark, as well as the presence of the secondary caudal keels, which are absent in the white shark.

Coloration

The dorsal and lateral surfaces of the porbeagle are dark blue to gray in color. The first dorsal fin is dark with an abruptly white or gray free rear tip. In Northern Hemisphere porbeagles, the ventral surface of the head and abdomen are white, with the color extending dorsally to the rear of the pectoral bases. In some of the adults of the Southern Hemisphere, the ventral surface of the head is dark and the abdomen is white with dark blotches. The white free rear tip on the dorsal fin distinguishes the porbeagle from both the salmon shark and the white shark.

Dentition

The porbeagle has moderately large blade-like teeth with lateral cusplets, which are small bumps or “mini-teeth” on either side of the tooth. The first upper lateral teeth have nearly straight cusps.

Denticles

Dermal denticles are flat and small with three teeth of which the median is the longest. There three ridges separated by valleys on each denticle (see figure). The skin feels soft and velvet-like.

Size, Age, and Growth

The porbeagle has a maximum total length of about 12 ft (365 cm) and maximum weight of over 500 lbs (230 kg). Maximum age is likely about 30 years. There is considerable variation in estimates for size at maturity for this species. The most recent studies indicate that females in the northern hemisphere mature at around 7.6 to 8.5 feet (232-259 cm) in total length, and females in the southern hemisphere at around 6.1 to 6.6 feet (185-202 cm). Males in the northern hemisphere mature at around 5.4 to 6.8 feet (165-207 cm). In the northwest Atlantic at least, these sizes correspond to a female age at first maturity of about 13 years and a male age at first maturity of about 8 years.

Thermoregulation

As with all other members of the family Lamnidae (the mackerel sharks), the porbeagle has the ability to maintain its body temperature above ambient water temperature. This is an unusual trait among fishes, possessed by only a few other fast-swimming fish, like tunas.

All lamnids have vascular counter-current heat exchangers (retia mirabilia) that allow them to retain the heat produced by their metabolic processes. These retes are located in the muscle and in the viscera. There are also vascular shunts that allow the shark to alter the route of blood flow, further regulating rates of heat gain and heat loss.

Porbeagles can raise their body temperature up to 12.5o to 18oF (-10.8o to -7.8oC) above the temperature of the surrounding water. This is an important adaptation to the cold waters that the porbeagle prefers and allows the porbeagle to be a very fast-swimming predator.

Food Habits

Porbeagles are opportunistic feeders. In the northwest Atlantic, their diet consists primarily (90%) of teleosts (bony fish). In the spring, these are mostly pelagic fish, like lancetfish, herring, sauries, and mackerels. In the fall, these are mostly groundfish, like sand lances, lumpsuckers, flounders, hakes, and cod. Cephalopods, like squid, are the second most common prey item.

Reproduction

In the Northern Hemisphere, porbeagles mate autumn-winter and give birth spring-summer. The little data that exists for the Southern Hemisphere populations indicates that they may be out of phase with those of the Northern Hemisphere, giving birth off New Zealand and Australia in winter.

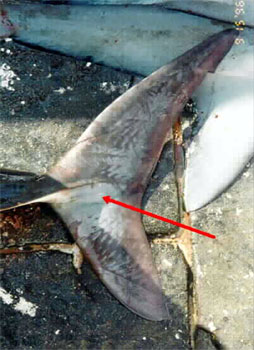

During mating, the male shark bites the female shark to hold onto her while they copulate. In this way, scientists can tell if females have recently mated.

Gestation is probably eight to nine months. Litters of 1-6 embryos have been recorded, but the usual number is 4, with 2 embryos per uterus. The porbeagle is ovoviviparous, meaning that it gives birth to live young, but in the uterus (womb), embryos have no placental or other direct connection to the mother. It is also oophagous, meaning embryos consume unfertilized yolk-filled eggs (ova) ovulated by the mother during the later stages of gestation. Pups are born at about 2.2 to 2.6 ft (68-80 cm) in length.

Predators

Aside from humans, there is little known about predators of the porbeagle shark. Because of its large size, an adult porbeagle would likely have very few predators. White sharks and orcas are potential candidates, but no records of predation by these species exist.

Taxonomy

The porbeagle was first validly described as Squalus nasus by Bonnaterre in 1788. Gunnerus had described it earlier in 1768 as Squalus glaucus, but this name was already in use for the blue shark, now Prionace glauca. The current valid name of this shark is Lamna nasus. The genus name Lamna is translated from Greek “lamna, -es” as a voracious fish while the species name nasus originates from Latin, meaning nose. Other synonyms for Lamna nasus include Squalus cornubicus and its spelling variant Squalus cornubiensis, S. pennanti, S.monensis, S. selanonus, Selanonius walkeri, Lamna punctata, L. pennanti, L. cornubica, L. philippi, L. whitleyi, Oxyrhina daekayi, and Isuropsis dekayi.

Prepared by: Brenda Roman