Megachasma pelagios

This rare and unusual shark has been encountered so infrequently that the scientific community has kept a detailed list and summaries of each encounter. They are likely diurnal following swarms of krill, from the surface of the open ocean during the day, and diving deep at night.

Order – Lamniformes

Family – Megachasmidae

Genus – Megachasma

Species – pelagios

Common Names

- Dutch: grootbekhaai

- English: Megamouth shark

- French: requin grande gueule

- Spanish: tiburón bocudo

Importance to Humans

Megamouth has probably been encountered more times than documented but fishermen likely release them due to their immense size.

Conservation

IUCN lists megamouth as “Least Concern”, but no real data on population sizes and distribution exists at this time.

> Check the status of the megamouth shark at the IUCN website.

Geographical Distribution

There have been 69 confirmed sightings. Locations include Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic Oceans. As with the two other filter-feeding sharks, the basking and whale sharks, this species is wide-ranging. However, the megamouth is considered to be a poor swimmer (Ebert et al., 2013). Genetic testing of samples collected from Taiwan and California showed no genetic diversity, suggesting a single highly migratory population (Liu et al., 2018).

> View list of confirmed megamouth sightings.

Habitat

The megamouth lives in the epipelagic (upper water column) open ocean. The 6th specimen ever captured was tagged and tracked for two days. It remained at a depth of 12 – 25 m (39 – 82 ft.) during the night, then dove to 120–160 m (390–520 ft.), at dawn and returned to shallow waters at dusk. This suggested that the species migrates vertically on a diel cycle (Anon, 1991a, b).

Biology

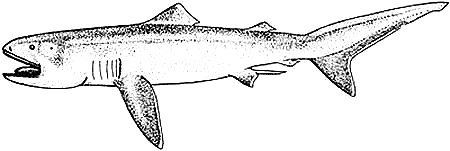

Distinctive Features

Body stout, tapering posteriorly. Head bulbous, broadly rounded snout. Moderately long gill slits. Mouth broad, terminal, corner extending behind eyes. Caudal peduncle without keels or ridges. First dorsal fin origin is closer to pectoral fin base than to base of pelvic fins; dorsal fins relatively low; second dorsal fin less than half size of first. Pectoral fins shorter than head length in adults. Caudal fin asymmetrical, with pronounced ventral lobe. Poor mobility likely is a reflection of its flabby body, soft fins, asymmetrical tail, lack of keels and weak calcification (Compagno, 2001).

Coloration

Dorsal surface of the body is blackish-brown. Ventral surface white. Areas between nostrils and eyes and between eyes and spiracles are paler. Lower jaw dark with silver tint and many small dark spots. Ventral side of head behind lower jaw light grey (Compagno, 2001).

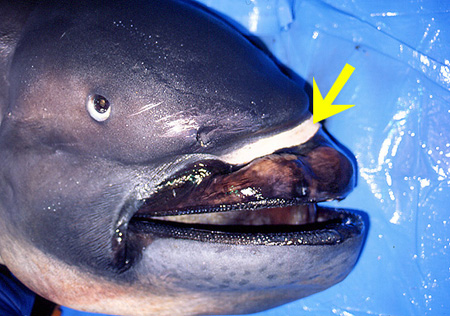

Silver oral membranes at the roof of the mouth. Tongue purplish brown with slight silvery tint on both sides. White band on the anterior surface of the snout. Band could be used in attracting prey, contrasting with the dark coloration of the snout (Taylor et al., 1983). This band may be related to the recognition of other individuals of the same species (Moris et al. 2014).

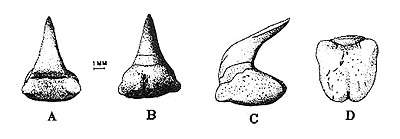

Dentition

The megamouth has approximately fifty rows of small and numerous teeth on each jaw, but only three rows are functional. Females usually have fewer teeth rows than males. Upper and lower jaws have a symphyseal (where the two halves of the jaw meet) toothless space, which is larger in upper jaw. The first five upper teeth are smaller than the first five lower teeth; the more distal upper teeth are smaller than the lower teeth; the cusps of the lower teeth are more acute and longer than those of the upper teeth (Compagno, 1990).

Denticles

Megamouth sharks have very small mucous (on the tongue) and dermal (on the skin) denticles that differ in shape and size at each region of the body. There are many pigment cells on the dorsal side, but none on the ventral side.

Size

Maximum size is at least 550 cm (17ft.). Males probably mature by 450-550 cm (13ft.) and female by 500 cm (16ft.) (Compagno, 2001).

Behavior

Megamouth, in contrast to many other deep-water sharks, shows a decrease in specific gravity in the form of a soft, and poorly calcified cartilaginous skeleton; very soft, loose skin; and loose connective tissue and muscles. Others epibenthic (live in the water just above the bottom) and epipelagic sharks often have an enlargement of their abdominal cavity and increased liver volume. The huge liver allows for greater production of liver oil in order to reduce specific gravity and increase hydrostatic support.

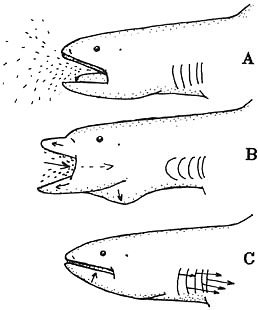

Food Habits

Precise details of feeding behavior are unknown. Scientists believe that this shark swims slowly through aggregations of euphausiid shrimp (“krill”) and other small prey with its mouth open (A). Protruding its jaws and expanding the buccal cavity in order to suck the prey inside (B). The mouth is closed and the jaws retracted. This action decreases the pharyngeal volume and makes possible the expelling of water through the gill openings (C) (Compagno, 1990).

Stomach Contents

All analyzed specimens presented euphausiid shrimp in the stomach, indicating a filter-feeding habit (Compagno 2001). The stomach of the first megamouth captured contained only one type of shrimp, Thysanopoda pectinata. The second megamouth’s stomach contents included fragments of euphasiids, copepods, and the jellyfish, Atolla vanhoeffeni. In general, euphasiids appear to predominate their diet (Yano et al. 1997).

Origin of Filter-Feeding

There are two conflicting hypotheses about the origin of filter-feeding in megamouth exist. The first theory suggests a single origin for this habit between megamouth and basking sharks. In contrast, the other suggests that adaptations for filter feeding evolved independently in the two lineages from different ancestral origins. Results of recent studies argue strongly in favor of the latter hypothesis. This makes sense when considering morphological and behavioral differences between the two sharks. The second hypothesis also suggests that megamouth may have evolved its distinctive feeding apparatus from an ancestral sand tiger-like shark (family Odontaspidae) through jaw size exaggeration, acquisition of papillose (bud-like) gill rakers, and modification of jaw protrusion for suction feeding.

Reproduction

Megamouths 2 and 6 were both mature males, and both showed evidence of recent mating. The claspers of 2nd were oozing spermatophores and those of the 6th specimen were abraded and bleeding, a common occurrence in sharks that have just mated. The 6th also had a fresh wound on the lower jaw, a feature found in other shark species that grasp one another’s mouth during mating. Megamouth 2 was taken in late November and the 6th in late October, these factors make scientists believe that Southern California in the fall may a mating ground (Lavenberg and Seigel, 1985; Lavenberg 1991).

The 7th megamouth observed, a 4.71 m (15.4 ft.) female, was concluded to be immature. This was based on her uteri only being enlarged posteriorly, a poorly developed ovary and ostium, and the small size of the oocytes. The ovary of the megamouth is similar to other mackerel sharks and suggesting that megamouth are aplacental viviparity, with embryos catching from eggs inside the mother. The embryos are likely oophagous (the first well-developed embryo eats the other eggs) (Ebert et al. 2013). The 12th megamouth captured is the only known mature female. With a total length of 5.44 m (17.8 ft.) and the expanded uteri measured 260 mm (10 in.). The right ovary possessed a large number of whitish yellow eggs (Yano, 1997).

Predators

The only confirmed event of predation involved sperm whales (Physeter macrocephalus). This occurred in Manado, North Sulawesi, Indonesia (30th August, 1998) near midday, while some researchers were observing the whales. The base of the 13th megamouth’s dorsal fin and the gills showed signs of the whales’ attack (Compagno, 2001).

Sperm whales are usually considered squid feeders but there are a few notes about small deep-sea sharks in their diet. This behavioral observation significantly alters our views on the relationship between whales and sharks.

Parasites

Almost all reported specimens show scars from the cookiecutter shark (Isistius brasiliensis). Cookiecutter sharks are small dogfish sharks that attach to prey with the help of suctorial (aiding in suction) lips, and a modified pharynx. The cookiecutter removes a conical plug of flesh from the sides of the prey, leaving a crater-like wound. This parasitic shark is presumed to be a vertical migrator on a diel cycle, spending the daytime in deep waters and ascending to midwater depths and to the surface at night. The similar suggested pattern of megamouth combined with its slow swimming speed would make it easy prey for the active cookiecutter shark (YAMAGUCHI and Na Ka Ya, 1997). Additionally, the (Dinemoleus indeprensus), has been collected from individuals (Nagasawa and Nakaya, 1997). Specimens of the cestode worm (Corrugatocephalum ouei) and the poorly known trypanorhynch (Mixodigma leptaleum) have been recovered from the intestine contents of the 7th megamouth (Caira et al, 1997). A microscopic parasite (Chloromyxum) was also found in this megamouth’s gall bladder (Yokoyama, 1997).

Taxonomy

When the first megamouth was captured in 1976, a new shark family, genus and species had to be erected. There are conflicting phylogenetic hypotheses regarding the evolutionary relationships between the Megachasmidae and other shark families. One theory suggests that the Megachasmidae is evolutionary derived and form a monophyletic (they have one single common evolutionary ancestor) family with basking sharks, Cetorhinidae. Others disagree with this idea and suggest that the Megachasmidae is relatively derived and forms a sister group to the Cetorhinidae, Lamnidae (mako, white and porbeagle sharks) and Alopiidae (thresher sharks). Recent studies suggest that Megachasma pelagios is the most primitive living species within the order Lamniformes, which contains all the aforementioned families, and has independently evolved the filter feeding mode, shared with the basking shark, Cetorhinus maximus (Martin, and Naylor, 1997). The currently valid genus Megachasma is derived from the Greek “megas, megalos” = great and “chasma” = cave, while the species name pelagios is also Greek, meaning of the sea.

Prepared by: Carol Martins, and Craig Knickle

Revised by: Tyler Bowling 2019

References

- Anon. 1991a. Megamouth reveals a phanton shark’s realm. Nat. Geographic 179:136.

- Anon. 1991b. Megamouth caught alive and studied. Internat. Soc. Cryptozool. (1SC) Newsletter 10: 1-3.

- Ebert, D.A., Fowler, S. and Compagno, L. 2013. Sharks of the World. Wild Nature Press, Plymouth.

- Yano, K., Morissey, J.F., Yabumoto, Y. and Nakaya, K. 1997. Biology of the Megamouth Shark. Tokai University Press, Tokyo, Japan.

- Compagno, L.J.V. 2001. Sharks of the World. An annotated and illustrated catalogue of the shark species known to date. Volume 2. Bullhead, mackerel and carpet sharks (Heterodontiformes, Lamniformes and Orectolobiformes). FAO, Rome.

- Taylor, L.R., L.J.V. Compagno, and P.J. Struhsaker. 1983. Megamouth A new species, genus, and family of lamnoid shark (Megachasma pelagios. family Megachasmidae) from the Hawaiian Islands. Proc. California Acad. Sci. ser a, 43(8): 87-110.

- Martin, A.P. and Naylor, G.J., 1997. Independent origins of filter-feeding in megamouth and basking sharks (order Lamniformes) inferred from phylogenetic analysis of cytochrome b gene sequences. Biology of the megamouth shark, pp.39-50.

- Moris, V., Behets Wydemans, C., Claes, J. and Mallefet, J., 2014. Light on skin properties of megamouth shark, Megachasma pelagios (Lamniforme). In 21st Benelux Congress of Zoology.

- Compagno, L.J.V., 1990. Relationships of the megamouth shark, Megachasma pelagios (Lamniformes: Megachasmidae), with comments on its feeding habits. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Technical Report, National Marine Fisheries Service, 90, pp.357-379.

- Liu, Shang-Yin ‘Vanson’; Joung, Shoou Jeng; Yu, Chi-Ju; Hsu, Hua-Hsun; Tsai, Wen-Pei; Liu, Kwang Ming., 2018. Genetic diversity and connectivity of the megamouth shark. PeerJ.

- Yano, K., Yabumoto, Y., Tanaka, S., Tsukada, O. and Furuta, M., 1997, November. Capture of a mature female megamouth shark, Megachasma pelagios, from Mie, Japan. In Proceedings of the 5th Indo-Pacific Fish Conference (pp. 335-49).

- Lavenberg, R.J. 1991. Megamania. Terra, 30(1): 30-39.

- Lavenberg, R.J. and J.A. Seigel. 1985. The Pacific’s megamystery-megamouth. Terra, 23(4): 30-31.

- YAMAGUCHI R. & K. NA KA YA, 1997. – Fukuoka megamouth, a probable victim of the cookie-cutter shark. 1,,: Biology of the Megamouth Shark (Yano K., Morrissey J.F., Yabumoro Y. & K. Nakaya, eds), pp. 171-175. Tokyo: Tokai Univ. Press.

- Nagasawa, K. and Nakaya, K., 1997. The Parasitic Copepod Dinemoleus indeprensus (Siphonostomatoida: Pandaridae) from the Megamouth Shark, Megachasma pelagios, from Japan. Biology of the Megamouth shark, p.177.

- Caira JN, Jensen K, Yamane Y, Isobe A, Nagasawa K. 1997. On the tapeworms of Megachasma pelagios: description of a new genus and species of lecanicephalidean and additional information on the trypanorhynch Mixodigma leptaleum. In: Biology of the Megamouth Shark (eds Yano K, Morrissey JF, Yabumoto Y, Nakaya K). Tokai University Press, Tokyo, pp. 181–191.

- Yokoyama, H., 1997. A Myxosporean Parasite of the Genus Chloromyxum (Protozoa: Myxozoa) from the Gall Bladder of a Megamouth Shark. K. Yano, JF Morrissey, Y. Yabumoto, and K, Nakaya, eds. Biology of the megamouth shark. Tokai University Press, Tokyo, pp.193-195.