Pterois volitans

This Indo-Pacific reef fish has become an invasive species in the Western Atlantic with few or no predators. This almond-shaped fish is covered in red and white zebra striping, and has long, elaborate fins and venomous spines. They can grow to between 12 and 15 inches long, and prefer living near rocky coral areas where they can hunt small fish and invertebrates, and then retreat into crevasses. Despite the high number of “stings” reported every year, this species is a very popular fish in the aquarium trade.

Order – Scorpaeniformes

Family – Scorpaenidae

Genus – Pterois

Species – volitans

Common Names

Members of the genus Pterois are collectively known as lionfishes, turkeyfishes, and firefishes. Pterois volitans is known by many common names, probably due to the fact that the species is widespread, easily observed, and potentially dangerous to humans. English language common names include red lionfish, butterfly cod, lion fish, lionfish, ornate butterfly-cod, peacock lionfish, red firefish, scorpion volitans, turkey fish, and turkeyfish. Other common names are cá mao tiên (Vietnamese), chale (Swahili), chavarali (Malayalam), deek al bahar (Arabic), drakfisk (Swedish), fang-hamas (Mahl), fanhaa mas (Maldivian), hana-minokasago (Japanese), ho (Marshallese), kale (Marshallese), laaligere (Carolinian), laffe volant (French), lakule (Carolinian), lepu-penganten (Malay), mirrginbina (Tokelauan), narwönö (Carlinian), nufu pabo (Marshallese), ominokasago (Japanese), phanhu-kuthi (Malayalam), poisson scorpion (French), poisson volant (French), poisson-dindon (French), pwenengec (Jawe), rotfeuerfisch (German), sausau-lele (Samoan), skrzydlica pstra (Polish), tataraihau (Tahitian), and tataraihu (Tuamotuan).

Importance to Humans

Although the red lionfish is valued as a food fish in many parts of its native range, its value as an aquarium animal or as a source of attraction to divers far exceeds its economic value as table fare. The red lionfish is a staple of the trade in aquarium fishes, an industry whose value worldwide is estimated to exceed a billion dollars. Similarly, recreational divers of areas where the red lionfish is found count the species among the many attractions of diving a tropical coral reef.

Published reports of this species in waters of the East Coast of the United States date to a number of individuals first observed off the coast of North Carolina in August, 2000. Since that time, numerous observations of red lionfish have been recorded from South Florida to Long Island, NY. The unexpected arrival of this species in the Atlantic has generated a storm of scientific and public inquiry largely regarding how the species came to be in the area and what impact it might have on area ecosystems.

The ballast water of large ocean going vessels is a documented means of dispersal for non-native marine and estuarine organisms, including fishes. Commercial vessels that anticipate traversing rough open seas often fill their ballast tanks with water to increase stability, only to release the water from these enormous containers upon arrival at their destination. In this way, many marine organisms have been transported to new areas. Given the planktonic nature of larval red lionfish or the fact that the species is purported to occur in some harbors, some speculate that it is not unreasonable to surmise that the species has gained a foothold on the U.S. east coast via ballast water transport.

Yet still others conclude that the species may owe its presence in U.S. waters to the deliberate release of captive specimens. Numerous fishes (mostly freshwater species) have been introduced to areas beyond their native range in this fashion and given the burgeoning population of the United States east coast and the popularity of aquarium fishes as a hobby, this is not an unreasonable assumption. A recent published summary of the red lionfish in U.S. waters favors this latter explanation as the most plausible means of introduction. Certainly the method is direct. Furthermore, a paper published in 1995 records evidence in support of the notion – the accidental release of a number of lionfish to Biscayne Bay, FL in 1992.

Regardless of the method of introduction the red lionfish appears to be established along the East Coast of the United States, as evidenced by its distribution and the presence of juveniles. In an attempt to better understand its potential impacts on its new environment a variety of studies are planned or in progress that aim to examine further the biology of this species. It is hoped that data gathered on red lionfish temperature tolerance, reproduction, foraging strategies, and predator defense, to name a few, will increase our ability to forecast the potential distribution and impact of this species in the Atlantic.

History has shown that any eradication efforts of an introduced species must be conducted in the early stages of introduction if there is to be any realistic expectation of success. So it comes as something of a surprise that at this time no published plan to eradicate the species has been enacted or recommended despite the enormous potential danger that red lionfish pose to both environmental and human health. To delay is folly. The lessons of non-indigenous biology are unequivocal in this regard. Eradication efforts planned too late more often than not reap nothing but costs.

Danger to Humans

The venomous nature of this species is substantial and a sting from the red lionfish constitutes a serious health emergency. Localized symptoms of envenomation by the red lionfish include but are not limited to, persistent, intense, throbbing, radiating, sharp pain at the site of envenomation, tingling sensations, sweatiness, and blistering. The worst cases of envenomation may cause systemic repercussions including headache, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, delirium, seizures, paralysis of limbs, a rise or drop in blood pressure, respiratory distress, heart complications including congestive heart failure, pulmonary edema, tremors, muscle weakness, and loss of consciousness. Basic treatment includes immersing the afflicted area in hot water (to 45° C) as past case histories informally indicate that certain components of red lionfish venom may be inactivated by heat. Professional medical attention should be sought in any case of red lionfish envenomation.

The red lionfish is aggressive, even engaging potential threats with a spines forward approach. This species should be treated with care at all times. Worldwide, scorpionfishes rank second only to stingrays in total number of envenomations, with an estimated occurrence of approximately 40,000 – 50,000 cases annually.

Conservation

Although the red lionfish is widely distributed, as a commercially valuable coral reef species the status of its various populations should be monitored. Additional systematic research may determine that this widely distributed species is in fact a species complex awaiting further scientific description.

This species is not listed as threatened or vulnerable by the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN). The IUCN is a global union of states, governmental agencies, and non-governmental organizations in a partnership that assesses the conservation status of species.

> Check the status of the red lionfish at the IUCN website.

Geographical Distribution

The native distribution of the red lionfish is restricted to appropriate reef habitats of the Indo-Pacific. This distribution encompasses an enormous area extending from western Australia and Malaysia east to French Polynesia and the United Kingdom’s Pitcairn Islands, north to southern Japan and southern Korea and south to Lord Howe Island off the east coast of Australia and the Kermadec Islands of New Zealand. In between, the species is found throughout Micronesia. The presence of a similar species, Pterois miles, may preclude the presence of the red lionfish in the area between the Red Sea and Sumatra. A published record of P. volitans from Inhaca Island, Mozambique, is presumably in error and more likely represents the more westerly P. miles. Recently, a number of specimens of red lionfish have been observed and/or captured off the eastern coast of the United States in various locales from Florida to New York as well as in waters off the Bahamas and as far south as the Turks and Caicos. Its presence in these waters may stem from the release of captive specimens along the southeast coast of the United States. In recent years, the numbers of lionfish in non-native waters appears to be increasing rapidly. By some estimates, lionfish populations have increased by 50% in the past two years (2004-2006). Scientists are currently researching the effects that lionfish are having on native marine communities.

Habitat

The red lionfish is an inhabitant of near and offshore coral and rocky reefs to depths of 50 meters. The species shows a clear preference for sheltering under ledges or in caves or crevices by day. In these refugia the species exhibits a nearly motionless posture, the head tilted slightly downward. Some sources also record red lionfish as occurring in bays, estuaries, and even harbors.

Biology

Distinctive Features

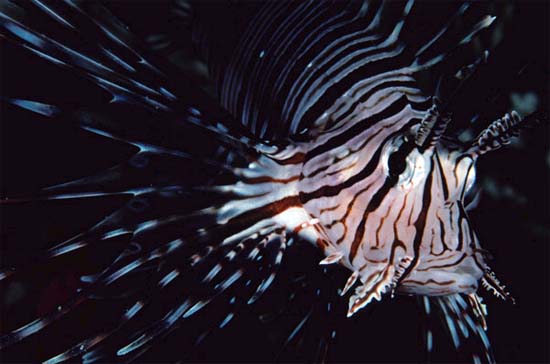

Lionfishes are among the most resplendent of all coral reef fishes, conspicuous for their elongate fin elements, bold patterning and seeming indifference to the potential threats posed by other reef dwelling predators. A member of the distinctive scorpion fish family, their extravagant dress and bold habits are notable even in relation to other scorpionfishes.

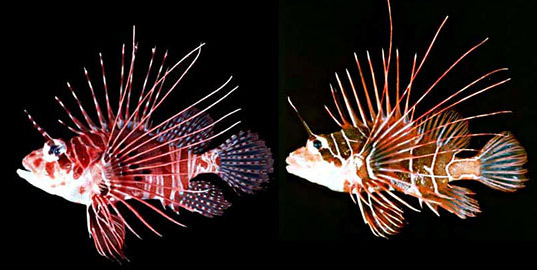

Pterois volitans, the red lionfish, is a member of the scorpionfish subfamily Pteroinae, which contains 5 genera representing a number of particularly interesting scorpionfishes. Among this group, the genusPterois stands out in features of body shape (dorso-laterally compressed), number of lengthy unbranched pectoral rays, and length of the dorsal spines in relation to body depth.

The genus Pterois contains eight species variously referred to as lionfishes, turkeyfishes, or firefishes. Relative to its seven congeners, Pterois volitans is diagnosed largely by differences in number of fin spines or rays, coloration, and scale type. Although not definitive, the presence of spots on the dorsal, anal, and caudal fins as well as the size of these spots (larger in the red lionfish than in the most closely related species) is useful in making a preliminary distinction between P. volitans and other lionfishes.

Naturally, the red lionfish shares many characters in common with scorpionfishes as a whole. Most notably these include the presence of numerous spiny projections and fleshy tabs on the head. The latter of these two structures may assist in camouflage by mimicking algal growth or by creating a visual disruption of the outline of the head or mouth (the business end of things from the perspective of small prey).

Scorpionfishes get their common name from their ability to defend themselves with a venomous “sting” or stab. Venom glands at the base of certain fin spines produce a number of toxins (collectively “venom”) that are injected in a potential predator via the spines. The venom of the red lionfish may be delivered by spines of the dorsal, anal and pelvic fins and is known to cause a severe reaction in humans. Numerous cases of human envenomation are documented by medical and scientific journals, symptoms of which are summarized in this document under the heading “danger to humans.”

While the “sting” of the red lionfish is painful and perhaps even potentially fatal to humans, some scorpionfishes may be unequivocally categorized amongst the most dangerous vertebrate sea creatures known. Certainly they are the most venomous of all fishes. Victims of envenomation by the reef stonefish,Synanceia verrucosa, are reported to have died from their wounds in a matter of an hour or two.

Coloration

The red lionfish is highly variable in appearance but is basically zebra-banded in red and white. The soft dorsal, anal, and caudal fins are spotted. Factors contributing to variation in this basic pattern may include the age of the fish, biogeography, and population genetics.

Dentition

The teeth of the red lionfish are numerous, but very small. They occur on the upper and lower jaws in densely packed bilateral clusters and in a small patch on the anterior roof of the mouth. Functionally, these teeth appear to be limited to grasping prey captured by the extraordinarily quick predatory strike of this species.

Size, Age, and Growth

The maximum size record for this species varies according to the source and can be confidently estimated to be between 300 – 380mm TL (11.8 – 15 inches). A related species, Pterois miles, which reaches a similar maximum size as that of P. volitans, is reported to achieve a maximum weight of 1.2 kg and this figure is probably a fair estimate of maximum weight for P. volitans.

Published age estimates for this species were not found while compiling this summary. Given the popularity of the species in public and private aquaria, records of maximum age at least for captive animals must surely exist.

Growth studies of the closely related P. miles indicate that post-larval growth of juveniles less than 80g in body weight is exponential.

Food Habits

The red lionfish is a solitary predator of small fishes, shrimps and crabs. Prey are stalked and cornered or made to feel so by the outstretched and expanded pectoral fins of the red lionfish in full ambush mode. Prey are ultimately obtained with a lightning-quick snap of the jaws and swallowed whole. Cannibalism has been observed for this species in the wild as well as for the closely related Pterois miles in captivity.

Given the tendency of the red lionfish to retreat to areas of hiding by day, this species is thought to be mostly nocturnal. However, red lionfish have been observed to feed during the day and studies of captive specimens imply that Pterois that have taken up refugia may simply be those individuals that have recently fed and are sated.

Reproduction

Red lionfish are external fertilizers that produce a pelagic egg mass following a courtship and mating process that is not well documented. The larvae of red lionfish, like those of many reef fishes, are planktonic. Data recorded for the closely related Pterois miles provide the best estimate of red lionfish early development. P. miles larvae settle out of the water column after a period of approximately 25 to 40 days, at a size of 10-12 mm in length.

Predators

Published records of natural predators of adult red lionfish are unknown. But again, studies of the closely related Pterois miles may provide us with some indication of the natural history of P. volitans. In the Gulf of Aqaba, Red Sea, the piscivorous cornetfish, Fistularia commersoni, appears to be a predator of Pterois miles. Judging by the presence of a specimen of P. miles in the stomach of a large F. commersoni, and its particular orientation therein, a published note concludes that cornetfish in the Red Sea may utilize their ambush tactics to seize lionfish safely from the rear, consuming them tail first.

As cornetfishes are widespread, effective piscivores, species sympatric with P. volitans may be predators of the same.

Other as yet undocumented predators of the red lionfish might include sharks, as many sharks are known to consume noxious or venomous organisms with no obvious ill effects.

Parasites

No information regarding parasites of free living red lionfish was found in compiling this summary.

Taxonomy

The red lionfish has been known to science since the time of Linnaeus, who described the species in 1758 based upon material collected by his friend and benefactor, the Dutch naturalist Johan Frederik Gronovius. Described as Gasterosteus volitans in Linnaeus’ 10th edition of Systema Naturae, the red lionfish was reclassified in the genus Pterois by 19th century naturalists. Synonyms (redundant species descriptions by workers either unaware of the original published description or by individuals falsely convinced that their study specimens represented a form different than that previously described) include Pterois zebra Quoy and Gaimard 1825, Pterois geniserra Cuvier 1829, Pterois cristatus Swainson 1839 and the subspecies Pterois volitans castus Whitley 1951. At present, 8 species of Pterois are currently recognized as valid.

Prepared by: Robert H. Robins