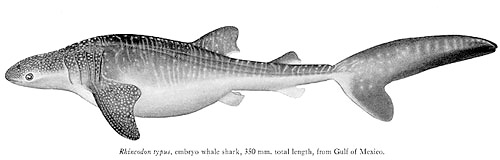

Rhincodon typus

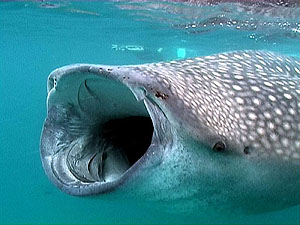

These sharks are recognizable not just for being the largest fish in the sea, but also for their unique patterns. They are filter feeders, often swimming near the surface of the open sea; they gulp in water and filter everything from plankton and fish eggs to crustaceans and schooling fish, to occasional larger prey like squid or tuna. Despite their size, they are considered harmless to humans, and will often interact docilely with divers.

Order – Orectolobiformes

Family – Rhincodontidae

Genus – Rhincodon

Species – typus

Common names

- English: Whale shark

- Afrikaans: walvishaai

- French: requin baleine chagrin

- Gela: bagea ni oka, bahiri

- German: rauhhai,walhai

- Japanese: jinbeizame

- Khmer: yaak

- Malay: yu paus

- Polish: rekin wielorybi

- Portuguese: tubarão baleia

- Spanish: dámero pez dama, tiburon ballena

- Swahili: vaame

- Tagalog: tuko

- Tamil: thimingal sura

- Visayan: tuki-tuki

Importance to Humans

Whale sharks are a part of the national and international trade, keystones of marine tourism, and often taken as bycatch by fisheries. The only fishery to exist in the Atlantic was in Cuba, which caught about 9 sharks annually, and was later shut down and banned in 1991. However, in the Indo-pacific, the amount of whale sharks targeted by fisheries has risen over the years because of the increasing economic value of the shark’s meat (Chen, 2002).

Until 2008, Taiwan caught an average of 100 whale sharks annually, for meat, oil, fins, or aquaria. Although Whale shark fins are rarely seen on the market when they appear they are highly-priced because of their difficult preparation and trophy-like status. Because of their value, opportunistic finning began in several countries including India and Taiwan (Chen, 2002). In India, harpooning allowed access to liver oils and flesh of the shark. Even though whale sharks are now protected in India and the Philippines, harpooning fisheries developed in other countries such as Iran and Pakistan (Akhilesh, 2013). The liver oils are often used for waterproofing fishing boats and other appliances, for the manufacture of shoe polish, and as a treatment for some skin diseases, while the flesh is occasionally eaten.

Whale sharks have been kept in specialized aquaria in Japan, China, and in the Georgia Aquarium (U.S.), but their large size and specialized diet exclude this species from mainstream aquarium species. In a few locations where the presence of whale sharks appears to be predictable, they are increasingly targeted by commercial tourist operations. By taking advantage of the surface feeding habits of the whale shark, the tourism industry has rapidly expanded around the globe, generating millions of dollars per country annually (Topelko, 2005).

Danger to Humans

Generally considered harmless. However, there have been a few cases of whale sharks ramming sportfishing boats, possibly after being provoked. Usually, the sharks are more at risk of being struck accidentally by vessels whilst basking or feeding on the surface.

Conservation

Threats to this species include bycatch, fisheries, vessel strikes, and poorly conducted tourism (Stacey, 2012). The whale shark is listed as “Vulnerable” with the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN). The whale shark is listed by the AFS (American Fisheries Society) as conservation dependent (reduced but stabilized or recovering under a continuing conservation plan) in both the U.S. Atlantic and the Gulf of Mexico. However, it is considered not at risk in the Gulf of California. In the Maldives and Philippines, there is legislation banning all fishing for whale sharks. This protection was introduced because of the possible serious impact that the fishery may be making on whale shark stocks (Colman, 1997).

The predictable occurrence of whale sharks in a few localities, such as in Western Australia, has led to the development of an expanding tourism industry (Meekan, 2006). In this area the whale shark is a protected species and its tourism has been managed through a system of controls, including the licensing of a limited number of operators tours. In addition, there have been calls from conservation-minded divers worldwide to refrain from riding, chasing, or in any way harassing any large marine animals, including whale sharks. Recently, some observations made on the Ningaloo Reef’s whale sharks provided the information that regular diving is a normal behavior of these sharks and not an avoidance reaction during contact with humans (Meekan, 2006). However, the natural variability in whale shark abundance and distribution, the reasons for aggregations at some areas, and the carrying capacity of the industry are still unknown. Consequently, evidence of any impact is difficult to obtain and interpret.

Recent research using mitochondrial DNA and microsatellite analysis has demonstrated that there exist two subpopulations of whale sharks. One lives in the Indo-Pacific Ocean and the other population in the Atlantic Ocean. The Indo-Pacific Ocean population ranges from the Western Indian Ocean, the Philippines, Taiwan, Thailand, and the Western and Central Pacific. The population size has shown a decrease from overfishing in this area. The Atlantic subpopulation is known to have more aggregations over feeding areas. The Atlantic population has decreased as well (Castro, 2007).

> Check the status of the whale shark at the IUCN website.

Geographical Distribution

The whale shark has a very widespread distribution, occurring in all tropical and warm temperate seas, except in the Mediterranean. It occurs throughout the Atlantic Ocean, from New York through the Caribbean to central Brazil and from Senegal to the Gulf of Guinea. It also occurs in the Indian Ocean, throughout the region, including the Red Sea and the Arabian Gulf. In the Pacific Ocean, it is found from Japan to Australia, off Hawaii, and from California to Chile (Sequeira, 2013).

Habitat

In contrast to most sharks from the same order (Orectolobiformes), which are benthic (live on or near the bottom) species, the whale shark is a pelagic (open sea) species. Studies reveal that this shark can reach depths of 1928 meters (6325.5 ft) (Tyminski, 2015) and prefers warm waters, with surface temperature around 21-30º C (69.8-86 F), marked by high primary productivity (plankton). They are often seen offshore but commonly come close inshore, sometimes entering lagoons or coral atolls. This species segregates by size and sex in most of the coastal feeding areas. The coastal feeding sites consist of mainly juvenile male sharks, with the largest congregation containing hundreds to thousands of individual sharks (Rohner, 2013). Whale sharks show site fidelity, where they continuously return to the same feeding site but are also highly migratory with daily movement of about 24-28 km (14.9-17.4 miles) (McCoy, 2018). Their movements might be related to local productivity and they are often associated with schools of pelagic fish that are probably feeding on the same prey organisms.

Different geographic locations appear to be preferred at various times of the year. Whale sharks alternatively may undertake either fairly localized or large-scale transoceanic migrations, the movements governed by the timing and location of production pulses and possibly by breeding behavior. Seasonal migrations have been postulated for various areas but more information is needed to confirm these patterns. Each March and April, whale sharks are known to be aggregate on the continental shelf of the central western coast of Australia, particularly in the Ningaloo Reef area (Fitzpatrick, 2006). A study was done in this area to provide information on the short-term movements and behavior of this species of shark. Whale sharks are thought to migrate to Ningaloo Reef each year to take advantage of the high zooplankton concentrations (Martin, 2007).

A few whale sharks were tracked and some behavioral observations were made while snorkeling in the area. The reaction of the sharks to snorkelers varied between ignoring them to slowly diving. At times when water was flowing out from the reef lagoon, possibly transporting potential prey outside the reef, the tracked sharks swam in large circles adjacent to passes in the reef. The whale sharks also made numerous dives throughout the observation period. It appears that these movements, up and down through the water column, were associated with feeding (Gunn, 1999). Whale sharks have smaller livers than most sharks and could conceivably control their buoyancy by swallowing some air as do the sand tiger sharks (Ondontaspis taurus).

Whale sharks were also observed near La Paz, Mexico. Researchers reported that when these sharks were not feeding at the surface, they swam practically without the head-turning, gulping, and rhythmical opening and closing of the gill slits, seen during feeding behavior(Rowat, 2012). The mouth was held slightly open, and the skin over the gill openings was quivering as water flowed steadily out the gill slits in the typical ventilation of pelagic sharks (Rowat, 2012).

Because of the broad geographical range, two main sub-populations exist which vary slightly in population size and population trend, Atlantic and Indo-Pacific (McKinney, 2017).

Distinguishing Characteristics

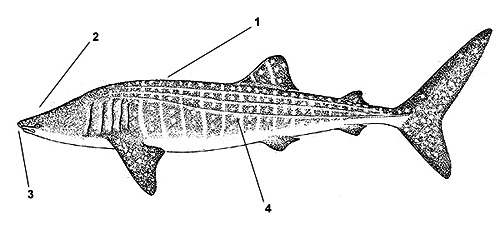

1. Back and sides marked with unique checkerboard pattern of light spots and transverse bars

2. Head is broad and flat with a short snout

3. Mouth is near the tip of the snout

4. Sides have three prominent ridges

Biology

Distinctive Features

A streamlined body and a depressed, broad, and flattened head characterize the whale shark (Compagno, 2005). The mouth is transverse, very large and nearly at the tip of the snout. Gill slits are very large, modified internally into filtering screens. The first dorsal fin is much larger than the second dorsal fin, and set rearward on the body (Compagno, 2005). The two lobed caudal fin (tail) is semi-lunate in adults; in small juveniles the upper lobe is considerably longer than the lower lobe. The whale shark has a unique “checkerboard” color pattern of light spots and stripes on a dark background (Compagno, 2005).

Coloration

Whale sharks are grayish, bluish or brownish above, with an upper surface pattern of creamy white spots between pale, vertical and horizontal stripes (Compagno, 2005). The belly is white. The function of the distinctive pattern of body mark is unknown. Many bottom-dwelling sharks have bold and disruptive body markings that act as camouflage through disruptive coloration (Compagno, 2005). The whale shark’s markings could be a result of its evolutionary relationship with bottom dwelling carpet sharks. Distinctive markings in a pelagic species could be linked to social activities such as postural displays and recognition processes (Compagno, 2005).

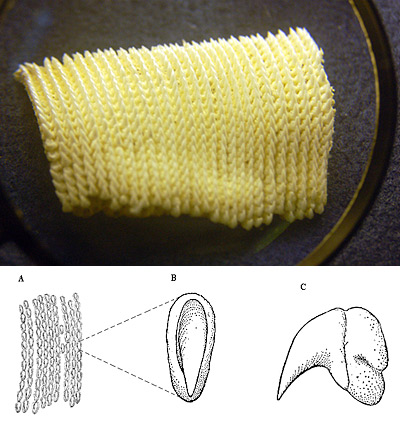

Dentition

Inside of the mouth next to the pharynx, the shark has 20 filtering pads in total. (10 on each side, then divided into upper and lower). These filtering pads allow the shark to sift through an average of 20,723 grams of plankton a day (Motta, 2010).

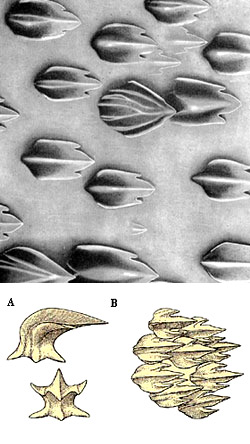

Dermal Denticles

The whale shark has unique denticles (tooth-like scales structures), each with an extremely strong central keel, no lateral keels, and a tri-lobed rear margin. It would appear that the denticles are hydrodynamically important in its pelagic lifestyle (Martin, 2007).

Size, Age & Growth

The whale shark is the largest living fish with the maximum size thought to be about 20m. The smallest free-living individuals are from 55cm (21.7 in.) long (Compagno, 2005). The size of these sharks at maturity is still being researched, but studies indicate that both male and female sharks reach maturity by 9m (29.5 ft) long (Colman, 1997). Age estimates for whale sharks are as high as 60 years, but no one really knows how long this species lives.

Food Habits

Whale sharks feed on a wide variety of planktonic (microscopic) and nektonic (larger free-swimming) prey, such as small crustaceans, schooling fishes, and occasionally on tuna and squids (Martin, 2007). Also, phytoplankton (microscopic plants) and macroalgae (larger plants) may form a component of the diet. Unlike most plankton feeding vertebrates, they do not depend on slow forward motion to filter, rather, they rely on a versatile suction filter-feeding method, which enables them to draw water into the mouth at higher velocities than other dynamic filter-feeders, like the basking shark. This enables the whale shark to capture larger more active nektonic prey as well as zooplankton aggregations (Motta, 2010).

Therefore, they are dependent on dense aggregations of prey organisms. The denser filter screens are efficient filters for short suction intakes, in contrast to the flow through systems of basking shark. Whale sharks are always seen feeding passively in a vertical or near vertical position with the head at or near the surface (Motta, 2010).

The whale shark feeds actively by opening its mouth, distending the jaws and sucking. Then it closes its mouth and the water flows out its gills. During the slight delay between closing the mouth and opening the gill flaps, plankton may be trapped against the dermal denticles lining the gill plates and pharynx (Motta, 2010). The fine sieve-like apparatus, a unique modification of the gill rakers, forms an obstruction to the passage of anything but fluid, retaining all organisms above 2 to 3mm (.07- .12 inches) in diameter. Practically nothing but water goes through this sieve. Individuals have also been observed coughing, a mechanism that is thought to be employed to clear or flush the gill rakers of accumulated food particles (Motta, 2010).

Whale sharks move their heads from side to side, vacuuming in seawater rich in plankton, or aggressively cut swathes through schools of prey. Groups of individuals have been observed feeding at dusk or after dark (Martin, 2007). The density of plankton probably is sensed by the well-developed nostrils, located on either side of the upper jaw, on the leading edge of the terminal mouth. The frequent turns may keep the whale sharks in the denser parts of the plankton patches, searching and scanning when an olfactory cue weakens on one side or the other (Martin, 2007).

The whale shark’s small eyes are located on the sides of the head. Because of this, vision may play a much smaller role than olfaction in directing the head turns during surface feeding. One live whale shark pup removed from its dead mother was maintained in captivity in Japan. It did not eat for the first 17 days, even though it swam constantly. This suggests that the pup had substantial stores of endogenous (stored) energy (Chang, 1997).

Reproduction

Historically, there was a great scientific debate about the mode of development of whale sharks. However, in 1995, an 11-meter female whale shark was harpooned off the eastern coast of Taiwan and 300 fetal specimens, ranging in length from 42 to 63cm, were taken from the two uteri (Compagno 2005). This discovery proved that the species is a live bearer, with an ovoviviparous (egg cases hatching in the mother’s uteri, with the female giving birth to live young) mode of development.

The egg-capsules of this whale shark were amber colored, with a smooth texture, and possessed a respiratory fissure (opening) on each side (Chang, 1997). The sex ratio was approximately 1:1. It would appear that female whale sharks give birth as they feed in the rich waters of the Kuroshio Current. It is also apparent that the southeast waters off Taiwan are an important birthing area during summer months. It is believed that the young measure 55-64 cm (21.7-25.2 in.) total length at birth (Chang, 1997).

Predators

A juvenile specimen was found in the stomach of a blue shark (Prionace glauca). Another specimen was found in the gut contents of a blue marlin (Makaira nigricans).

At Ningaloo Reef, great white sharks (Carcharodon carcharias), and tiger sharks (Galeocerdo cuvier) have been reported to attack whale sharks when they congregate (Fitzpatrick, 2006).

Parasites

Many parasitic copepods were found on the lining of the pharynx of a small (60cm total length) whale shark from Taiwan.

Taxonomy

The whale shark was first described and named by Andrew Smith in 1828, based on a specimen harpooned in Table Bay, South Africa. Historically, there have been many synonyms (alternative scientific names) for family, genus and species names. The first scientific printing of the genus name appeared as Rincodon, despite Smith’s desired name of Rhineodon. However, in 1984 the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature suppressed previous generic variations in favor of genus name Rhincodon, and the family name Rhincodontidae. Others generic names formerly used includeRhiniodon and Rhineodon and the family names Rhiodontidae and Rhineodontidae. Systematically, Rhincodontidae is placed in the order Orectolobiformes, which also includes families such as Ginglymostomatidae (nurse sharks) and Orectolobidae (wobbegongs). The interrelationships between these families are based on anatomical and morphological similarities.

Synonyms for the whale shark in past scientific literature include Rhinodon typicus Müller & Henle 1839, Rhinodon typicusSmith 1845, Micristodus punctatus Gill 1865, and Rhinodon pentalineatus Kishinouye 1901.

Rhincodon typus is derived from the Greek words “rhyngchos” = rasp and “odous” = tooth. The species name is translated as type.

Revised by Macey Sigel and Tyler Bowling 2020

Prepared by: Carol Martins & Craig Knickle

References

- Akhilesh, K.V., Shanis, C.P.R., White, W.T., Manjebrayakath, H., Bineesh, K.K., Ganga, U., Abdussamad, E.M., Gopalakrishnan, A. and Pillai, N.G.K., 2013. Landings of whale sharks Rhincodon typus Smith, 1828 in Indian waters since protection in 2001 through the Indian Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972. Environmental biology of fishes, 96(6), pp.713-722.

- Castro, A.L.F., Stewart, B.S., Wilson, S.G., Hueter, R.E., Meekan, M.G., Motta, P.J., Bowen, B.W. and Karl, S.A., 2007. Population genetic structure of Earth’s largest fish, the whale shark (Rhincodon typus). Molecular Ecology, 16(24), pp.5183-5192.

- Chang, W.B., Leu, M.Y. and Fang, L.S., 1997. Embryos of the whale shark, Rhincodon typus: early growth and size distribution. Copeia, 1997(2), pp.444-446.

- Chen, C.T., Liu, K.M. and Joung, S.J., 2002. Preliminary report on Taiwan’s whale shark fishery. In Elasmobranch Biodiversity, Conservation and Management: Proceedings of the International Seminar and Workshop, Sabah, Malaysia, July 1997 (pp. 162-167). IUCN Gland, Switzerland.

- Colman, J.G., 1997. A review of the biology and ecology of the whale shark. J. Fish Biol. 1997(51) pp. 1219-1234

- Compagno, L., Dando, M. and Fowler, S., 2005. A field guide to the sharks of the world.

- Fitzpatrick, B., Meekan, M. and Richards, A., 2006. Shark attacks on a whale shark (Rhincodon typus) at Ningaloo Reef, Western Australia. Bulletin of Marine Science, 78(2), pp.397-402.

- Gunn, J.S., Stevens, J.D., Davis, T.L.O. and Norman, B.M., 1999. Observations on the short-term movements and behaviour of whale sharks (Rhincodon typus) at Ningaloo Reef, Western Australia. Marine Biology, 135(3), pp.553-559.

- Martin, R.A., 2007. A review of behavioural ecology of whale sharks (Rhincodon typus). Fisheries Research, 84(1), pp.10-16.

- McCoy, E., Burce, R., David, D., Aca, E.Q., Hardy, J., Labaja, J., Snow, S.J., Ponzo, A. and Araujo, G., 2018. Long-term photo-identification reveals the population dynamics and strong site fidelity of adult whale sharks to the coastal waters of Donsol, Philippines. Frontiers in Marine Science, 5, p.271.

- McKinney, J.A., Hoffmayer, E.R., Holmberg, J., Graham, R.T., Driggers III, W.B., de la Parra-Venegas, R., Galván-Pastoriza, B.E., Fox, S., Pierce, S.J. and Dove, A.D., 2017. Long-term assessment of whale shark population demography and connectivity using photo-identification in the Western Atlantic Ocean. PloS one, 12(8), p.e0180495.

- Meekan, M.G., Bradshaw, C.J., Press, M., McLean, C., Richards, A., Quasnichka, S. and Taylor, J.G., 2006. Population size and structure of whale sharks Rhincodon typus at Ningaloo Reef, Western Australia. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 319, pp.275-285.

- Motta, P.J., Maslanka, M., Hueter, R.E., Davis, R.L., De la Parra, R., Mulvany, S.L., Habegger, M.L., Strother, J.A., Mara, K.R., Gardiner, J.M. and Tyminski, J.P., 2010. Feeding anatomy, filter-feeding rate, and diet of whale sharks Rhincodon typus during surface ram filter feeding off the Yucatan Peninsula, Mexico. Zoology, 113(4), pp.199-212.

- Rohner, C.A., Pierce, S.J., Marshall, A.D., Weeks, S.J., Bennett, M.B. and Richardson, A.J., 2013. Trends in sightings and environmental influences on a coastal aggregation of manta rays and whale sharks. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 482, pp.153-168.

- Rowat, D. and Brooks, K.S., 2012. A review of the biology, fisheries and conservation of the whale shark Rhincodon typus. Journal of fish biology, 80(5), pp.1019-1056.

- Sequeira, A.M., Mellin, C., Meekan, M.G., Sims, D.W. and Bradshaw, C.J., 2013. Inferred global connectivity of whale shark Rhincodon typus populations. Journal of Fish Biology, 82(2), pp.367-389.

- Stacey, N.E., Karam, J., Meekan, M.G., Pickering, S. and Ninef, J., 2012. Prospects for whale shark conservation in Eastern Indonesia through bajo traditional ecological knowledge and community-based monitoring. Conservation and Society, 10(1), p.63.

- Topelko, K.N. and Dearden, P., 2005. The shark watching industry and its potential contribution to shark conservation. Journal of Ecotourism, 4(2), pp.108-128.

- Tyminski, J.P., de la Parra-Venegas, R., Cano, J.G. and Hueter, R.E., 2015. Vertical movements and patterns in diving behavior of whale sharks as revealed by pop-up satellite tags in the eastern Gulf of Mexico. PloS one, 10(11), p.e0142156.