Sphyrna lewini

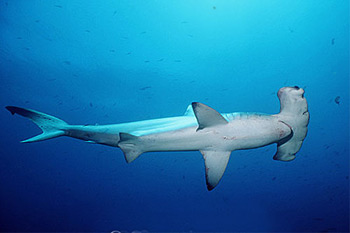

Named for their scallop like cephalophoil (‘hammer head’) these large sharks are open-water hunters. Using their impressive cranium to detect even the most hidden of prey.

Order – Carcharhiniformes

Family – Sphyrnidae

Genus – Sphyrna

Species – lewini

Common Names

- English: scalloped hammerhead, bronze hammerhead shark, hammerhead, hammerhead shark, kidney-headed shark, scalloped hammerhead shark, and southern hammerhead shark

- Arabic: abul-garn, jarjur

- Afrikaans: skulprand-hamerkop

- Bikol: krusan

- Dutch: geschulpte hamerhaai

- Finnish: kampavasarahai

- French: requin marteau

- Greek: ktenozygena

- Hawaiian: mano kihikihi

Japanese: aka-shumokuzame - Malayalam: chadayan sravu

- Malayan: jerong tenggiri, yu palang

- Maldivian: kalhigandu miyaru

- Polish: Glowomlot tropikalny

- Portugese: cação-cornudo

- Portuguese: peixe-martelo

- Spanish: cachona, cornuda, morfillo, pez martillo, tiburón martillo

Importance to Humans

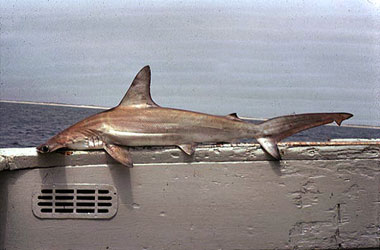

The scalloped hammerhead is commercially fished, in addition to being a sought after gamefish by sport anglers. It is readily accessible to inshore fishers as well as offshore commercial operations. This species tendency to aggregate in large groups making capture in large numbers on longlines, bottom nets and trawls even easier. This has led to complete die off of populations in certain areas (Maguire et al. 2006). Although the meat is sold, this species is also highly regarded for its fins and hides. Hammerhead fins have represented up to 5% of the fin market in China at times (Clarke et al. 2006a). This 5% is comprised of up to 2.7 million S. zygaena or S. lewini (Clarke et al. 2006b). The remainder of the shark is used for vitamins and fishmeal. Scalloped hammerhead pups reside in shallow coastal nursery areas making them quite vulnerable to fishing pressures.

Danger to Humans

Hammerheads are considered potentially dangerous sharks. According to the International Shark Attack File, there have been 17 unprovoked attacks for the genus Sphyrna, though none were fatal. Scalloped hammerheads have been reported to display threat postures when closely approached by divers on some occasions while other times they show no aggressive behaviors.

Conservation

The IUCN lists scalloped hammerheads as “Critically Endangered”. However little management exists to protect the species in international waters. Due to their migratory schooling behavior, large groups can be harvested in short time. Making them even more at risk from fishing pressures. While likely a great number are also bycatch, different species of hammerheads are sometimes difficult to identify by fishermen, resulting in insufficient data on bycatch’s true impact on the species.

> Check the status of the scalloped hammerhead at the IUCN website.

The IUCN is a global union of states, governmental agencies, and non-governmental organizations in a partnership that assesses the conservation status of species.

Geographical Distribution

Found globally, residing in coastally in warm, temperate, and tropical seas. In the western Atlantic, this shark ranges from New Jersey (US) to Brazil including the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea; and in the eastern Atlantic from the Mediterranean Sea to Namibia. Distribution in the Indo Pacific includes from South Africa to the Red Sea, throughout the Indian Ocean, and from Japan to New Caledonia, Hawaii, and Tahiti. In the eastern Pacific S. lewini are found from southern California to Ecuador and occasionally as far as Peru. In Australia, they are commonly seen in at the northwestern coast, though they are found throughout Australian waters (Compagno, 2005; Froese et al. 2008).

Habitat

This coastal pelagic species, is often found near continental and insular shelves as well as neighboring deep water. They have been recorded at depths of 275m (902 ft.). Additionally they have been observed close to shore and even entering estuarine habitats as well as deep offshore waters (Compagno, 2005). Scalloped hammerheads spend most of the day closer inshore, moving offshore to hunt at night. Adults generally spend the majority of their time off shore, and form schools segregated by sex. Females generally mature faster and at a smaller size than males, moving offshore once they have reached maturity. During the seasonal migrations the species can be seen in large schools heading north for the summer months (Clarke 1971, Bass et al. 1975, Klimley and Nelson 1984, Branstetter 1987, Klimley 1987, Chen et al. 1988, Stevens and Lyle 1989).

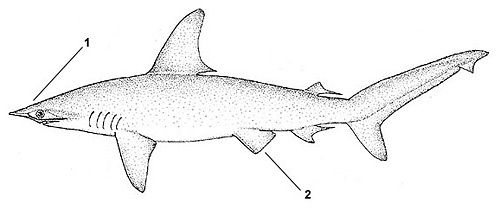

Distinguishing Characteristics

1. Head broadly arched and hammer-shaped and marked by a prominent indentation at midline (“scalloped”)

2. Pelvic fins with straight rear margins

Biology

Distinctive Features

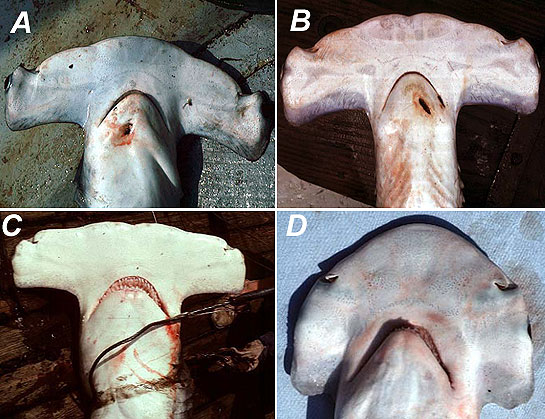

The scalloped hammerhead is distinguished from other hammerheads by an indentation located in the center of its laterally expanded head. As well smaller notches line the broadly arched hammer, granting them a “scalloped” head. The mouth is broadly arched and the rear margin of the head is slightly swept backward. The body is fusiform (tapering at both ends), moderately slender with a large first dorsal fin and low second dorsal and pelvic fins. The first dorsal is mildly curbed with its origin over or slightly behind the insertion point of the pectoral fins and the rear tip in front of the origins of the pelvic fin. The pelvic fin has a straight posterior margin while the anal fin is deeply notched on the posterior margin. The second dorsal fin has a posterior margin that is approximately twice the height of the fin, with the free rear tip nearly reaching the origin of the upper caudal lobe (Compagno, 2005).

Within the hammerhead family, the species are differentiated from each other by variations within the cephalophoil. The great hammerhead (S. mokarran) is distinguished by its T-shaped head that has an almost straight front edge as well as a notch in the center. Additionally, its pelvic fins have curved rear margins, while the scalloped hammerhead has straight posterior edges. The bonnethead (S. tiburo) is much easier to identify with a shovel-shaped head. The smooth hammerhead (S. zygaena) looks closest to its scalloped cousin. It is differentiated by its broad, flat un-notched head and smooth back, lacking a mid-dorsal ridge. Its first dorsal fin is moderately tall with a rounded apex and is falcate (strongly curbed or hook like) in shape with a free rear tip in front of the origin of the pelvic fins. The origin of this first dorsal is located over the pectoral fin insertions. The low second dorsal fin is shorter than the anal fin, with the free rear tip not extending to the precaudal pit. Pelvic fins are not falcate with straight of slightly concave posterior margins. The pectoral fins have only slightly falcate posterior margins. The anal fin has a deeply notched posterior margin.

Coloration

Brownish-gray to bronze or olive on the dorsal (top) body’s, with a pale yellow or white ventrally (bottom). Juveniles have dark pectoral fin, lower caudal and second dorsal fin tips while adults have dusky pectoral fin tips with no other distinctive markings (Compagno, 2005). Pups have been reported to ‘tan’ in the shallow waters of their nurseries, darkening in color (Lowe and Goodman-Lowe, 1996)

Dentition

The teeth are small with smooth or slightly serrated cusps on large bases. The upper jaw teeth are narrow and triangular with the first three nearly symmetrical and erect. Progressing towards the corners, the teeth become nearly straight along the inner margins and more deeply notched along the outer margins. Lower jaw teeth are more erect and slender than upper.

Denticles

Thin and moderately arched, with 3 sharp ridges in small individuals and 4 or 5 on larger sharks. These ridges run about half the length of each denticle (Tanaka et al, 2002).

Size, Age, and Growth

Maximum size has been varied in reports over the years from 219-340 cm (7.2-11 ft.) for males and 296-346 cm (9.7-11.3 ft.) for females (Clarke, 1971; Bass et al., 1975; Klimley and Nelson, 1984; Branstetter, 1987; Chen, et al. 1988; Stevens and Lyle, 1989; Chen et al., 1990). There are additional reports of larger individuals reaching 430 cm (14 ft.). This confusion may be due to populations in different parts of the world maturing at altered rates (Piercy et al. 2007; Chen et al., 1990; Anislado-Tolentino and Robinson-Mendoza 2001). The reason behind these differing population growth rates is still under debate. Their life span is thought to be over 30 years.

Food Habits

Scalloped hammerheads feed primarily on teleost fishes and a variety of invertebrates as well as other sharks and ray. Common prey: small schooling fish such as sardines, conger eels, many reef fish species, squid, octopus, crustaceans as well as smaller elasmobranchs such as blacktip reef sharks, angelsharks and stingrays. Up to 50 or more stingray spines are often found in the mouth and digestive systems of hammerhead sharks, a price to pay for a favorite meal. (Bigelow and Schroeder, 1948; Clarke, 1971; Bass et al., 1975; Compagno, 1984; Branstetter, 1987; Stevens and Lyle, 1989).

Reproduction

S. lewini are viviparous with the eggs hatching inside the body being nourished by a yolksac. Gestation lasts 9-12 months, with pups being born in spring and summer. Females can breed every year producing 12-41 embryos, each 31-57 cm (1-2 ft.) long (Castro 1983; Compagno 1984; Branstetter 1987; Chen et al. 1988; Stevens and Lyle 1989; Chen et al. 1990; Oliveira et al. 1991, 1997; Amorim et al. 1994; White et al. 2008). Juveniles spend their first two years inshore, though predation is high (Holland et al., 1993). Their main predators are other hammerhead species including adults of their own kind. This elevated rate of predation may explain the high fecundity of the species (Clarke, 1971; Branstetter, 1987; Branstetter, 1990; Holland et al., 1993).

Predators

Larger sharks will prey on small or injured scalloped hammerheads, while there are no major predators of the adults of this species.

Parasites

External leeches (Stilarobdella macrotheca) and copepods (Alebion carchariae, A. elegans, Nesippus crypturus, Kroyerina scotterum) often parasitize scalloped hammerheads. To deal with these pest hammerheads often visit cleaning stations, allowing cleaner wrasses to pick parasites from their skin and from inside their mouths.

Taxonomy

Originally described as Zygaena lewini by Griffith and Smith in 1834. The shark was later renamed Sphyrna lewini (Griffith and Smith, 1834), which remains its current identification. The name Sphyrna translates from Greek as “hammer”, referring to the head shape of this genus. Synonyms used in past scientific literature to refer to the scalloped hammerhead include Cestracion leeuwenii (Day 1865), Zygaena erythraea (Klunzinger 1871), Cestracion oceanica (Garman 1913), and Sphyrna diplana (Springer 1941).

Revised by: Tyler Bowling 2019

Prepared by: Cathleen Bester

References

- Amorim, A.F., Arfelli C.A. and Fagundes, L. 1998. Pelagic elasmobranchs caught by longliners off southern Brazil during 1974–97: an overview. Marine and Freshwater Research 49: 621–632.

- Anislado-Tolentino, V. and Robinson-Mendoza, C. 2001. Age and growth of the hammerhead shark Sphyrna lewini (Griffith and Smith, 1834) along the central Pacific coast of México. Ciencias Marinas 27(4): 501-520.

- Bass, A.J., D’Aubrey, J.D. and Kistnasamy, N. 1975. Sharks of the east coast of southern Africa. III. The families Carcharhinidae (excluding Mustelus and Carcharhinus) and Sphyrnidae. South African Association for Marine Biological Research. Oceanographic Research Institute. Investigational Reports.

- Branstetter, S. 1987. Age, growth and reproductive biology of the Silky Shark, Carcharhinus falciformis, and the Scalloped Hammerhead, Sphyrna lewini, from the northwestern Gulf of Mexico. Environmental Biology of Fishes 19: 161–173.

- Branstetter, S. 1990. Early life history implications of selected carcharhinoid and lamnoid sharks of the northwest Atlantic. NOAA Technical Report NMFS.

- Castro, J.I. 1983. The Sharks of North American Waters. Texas A. and M. University Press, College Station, USA.

- Chen, G.C.T., Leu, T.C. and Joung, S.J. 1988. Notes on reproduction in the scalloped hammerhead, Sphyrna lewini, in northeastern Taiwan waters. Fisheries Bulletin 86(2).

- Chen, G.C.T., Leu, T.C., Joung, S.J. and N.C.H. Lo. 1990. Age and growth of the Scalloped Hammerhead, Sphyrna lewini, in northeastern Taiwan waters. California Wild (formerly known as Pacific Science) 44(2): 156–170.

- Clarke, T.A. 1971. Ecology of the scalloped hammerhead shark, Sphyrna lewini, in Hawaii. California Wild (formerly known as Pacific Science) 25: 133–144.

- Clarke, S.C., Magnussen, J.E., Abercrombie, D.L., McAllister, M.K. and Shivji, M.S. 2006. Identification of Shark Species Composition and Proportion in the Hong Kong Shark Fin Market Based on Molecular Genetics and Trade Records. Conservation Biology 20(1): 201-211.

- Clarke, S.C., McAllister, M.K., Milner-Gulland, E.J., Kirkwood, G.P., Michielsens, C.G.J., Agnew, D.J., Pikitch, E.K., Nakano, H. and Shivji, M.S. 2006. Global Estimates of Shark Catches using Trade Records from Commercial Markets. Ecology Letters 9: 1115-1126.

- Compagno, L.J.V. 1984. Sharks of the World. An annotated and illustrated catalogue of shark species to date. Part II (Carcharhiniformes). FAO Fisheries Synopsis, FAO, Rome.

- Compagno, L.J.V. 2005. Sharks of the World. An annotated and illustrated catalogue of the shark species known to date. Volume 3: Carcharhiniformes. FAO, Rome.

- Froese, Ranier; Pauly, Daniel (eds.). 2008. Sphyrna lewini. FishBase.

- Holland, K.N., Wetherbee, B.M., Peterson, J.D. and Lowe, C.G. 1993. Movements and distribution of hammerhead shark pups on their natal grounds. Copeia 1993(2): 495–502

- Klimley, A.P. and Nelson, D.R. 1984. Diel movement patterns of the scalloped hammerhead shark (Sphyrna lewini) in relation to El Bajo Espiritu Santo: a refuging central-position social system. Behavioural Ecology and Sociobiology 15: 45–54.

- Klimley, A.P. 1987. The determinants of sexual segregation in the scalloped hammerhead shark, Sphyrna lewini. Environmental Biology of Fishes 18(1): 27–40.

- Lowe, C. and Goodman-Lowe, G., 1996. Suntanning in hammerhead sharks. Nature, 383(6602), p.677.

- Maguire, J.-J., Sissenwine, M., Csirke, J., Grainger, R. and Garcia, S. 2006. The state of world highly migratory, straddling and other high seas fishery resources and associated species. FAO Fisheries Technical Paper. FAO, Rome, Italy.

- Oliveira, M.A.M., Amorim, A.F. and Arfelli, C.A. 1991. Estudo biología-pesqueiro de tubaries peligicos capturados no sudeste e sul do Brasil. IX Encontro Brasileiro de Ictiologia. Maringñ Paran Brasil. (Abstract).

- Oliveira, M.A.M. 1997. Estudo comparativo da dieta de R. lalandi e de jovens de S. lewini desembarcados na Praia das Astúrias (Guaruj). (Abstract).

- Piercy, A.N., Carlson, J.K., Sulikowski, J.A. and Burgess, G. 2007. Age and growth of the scalloped hammerhead shark, Sphyrna lewini, in the north-west Atlantic Ocean and Gulf of Mexico. Marine and Freshwater Research 58: 34-40.

- Stevens, J.D. and Lyle, J.M. 1989. The biology of three hammerhead sharks (Eusphyrna blochii, Sphyrna mokarran and S. lewini) from Northern Australia. Australian Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research 40: 129–146.

- Tanaka, S., Kitamura, T. and Nakano, H., 2002. Identification of shark species by SEM observation of denticle of shark fins. Collective Volume of Scientific Papers ICCAT, 54, pp.1386-1394.

- White, W.T., Bartron, C. and Potter, I.C. 2008. Catch composition and reproductive biology of Sphyrna lewini (Griffith & Smith) (Carcharhiniformes, Sphyrnidae) in Indonesian waters. Journal of Fish Biology 72(7): 1675–1689.