Sphyrna mokarran

The great hammerhead is the largest of the hammerheads in the family Sphyrnidae. The “hammer head”, or cephalophoil, is straight and square relative to the major axis of the body. The body is stout and classically shark-shaped with a markedly tall, curved, first dorsal fin. The great hammerhead is dusky brown to light gray on the dorsal surface, fading to a cream-colored underside, with an asymmetrical caudal fin. They can reach a maximum length of 18-20 feet (Compagno et al., 2005). This warm-water, coastal shark eats bony fishes and invertebrates, as well as other sharks and rays (Denham et al., 2007). Because of their size and unpredictable nature, they should be treated with caution (ISAF 2018).

Fun Fact: As with all sharks and rays, hammerheads have small pores or “ampullae of Lorenzini”, distributed along the ventral surface of their head. The pores are gel-filled and serve as highly sensitive electrical receptors that are used, among other things, to detect the electrical signals that are emitted by potential prey items – including those that are buried under the sand such as stingrays.

Order – Carcharhiniformes

Family – Sphyrnidae

Genus – Sphyrna

Species – mokarran

Common Names

English language common names include great hammerhead, squat-headed hammerhead shark (Denham, et al. 2007). Other common names used are:

Arabic: Abu Garn, Akran, Jarjur

Finnish: Isovasarahai

French: Grand requin marteau

German: Großer hammerhai

Greek: Megalozygena

Italian: Grande squalo martello, Pesce martello maggiore

Japanese: Nami-shumokuzame, Hira-shumokuzame

Malay: Hiu tukul, Hiu parang

Polish: Glowomlot olbrzymi

Portuguese: Cação-martelo, Cambeva, Martello, Peix martelo

Somali: Cawar

Spanish: Cachona, Cachona Grande, Cornuda de ley, Cornuda gigante, pez martillo, tollo cruz, martillo

Swahili: Papa mbingusi

Importance to Humans

Great hammerheads are fished both commercially and recreationally and are highly valued for their large fins in the Asian fin trade. The meat is rarely consumed. Liver oil is used in vitamin production, hides are used for leather, and carcasses for fishmeal. Although not generally a targeted species, the great hammerhead is regularly caught in tropical regions with longlines, bottom nets, hook-and-line, and trawls (Denham et al., 2007). They are also popular with recreational fisherman who often fish for them from the shoreline with surface baits. While these animals put up an exciting fight, they tire quickly and are some of the more physiologically fragile species

Danger to Humans

According to the International Shark Attack File, there have been 17 unprovoked attacks with no fatalities for all species of the genus Sphyrna. However, few of the attacks can be directly attributed to this species as it is generally difficult to distinguish among species of hammerheads involved in attacks. Due to its large size and the variety of prey items this species will consume, this species should be treated with respect and caution (ISAF, 2018).

View shark attacks by species on a world mapConservation

IUCN Red List Status: Endangered

In the US, hammerheads (with the exception of the bonnethead which is a much smaller coastal species) are grouped with large coastal species, a group that biologists consider to be particularly vulnerable to overfishing. Although not targeted, the Great hammerhead is taken by gillnet and longline and as bycatch in driftnet fisheries. Mortality is greater than 90% although little data is available about the impact of fishing on population health. Different species of hammerheads are often difficult to distinguish in high seas fisheries unless trained observers are on board. As a result, bycatch data are seldom broken down by species. Great hammerheads are highly sought after by the fin industry. Often, the fins are illegally removed from the animal and the body discarded at sea, without the catch being reported. Several countries and organizations including the US, Australia, and EU have adopted shark finning bans to prevent this practice (Denham et al., 2007).

> Check the status of the great hammerhead at the IUCN website.

The IUCN is a global union of states, governmental agencies, and non-governmental organizations in a partnership that assesses the conservation status of species.

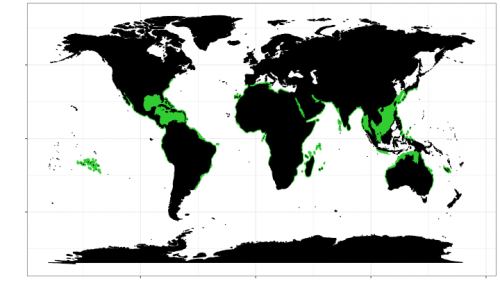

Geographical Distribution

Circumtropical in distribution, the great hammerhead is found in coastal warm temperate and tropical waters within 40°N – 35°S latitude (Denham et al., 2007). In the western Atlantic Ocean, it ranges from North Carolina (US) south to Uruguay, including the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean regions. In the eastern Atlantic, it ranges from Morocco to Senegal, including the Mediterranean Sea. Distribution of the great hammerhead includes the Indian Ocean and the Indo-Pacific region from the Ryukyu Islands to New Caledonia and French Polynesia. In the eastern Pacific it ranges from southern Baja, California (US) through Mexico, south to Peru. The great hammerhead is considered a highly migratory species within Annex I of the 1982 Convention on the Law of the Sea (FAO 1994).

Habitat

This large coastal/semi-oceanic shark is found far offshore to depths of 300m (Myers, 1999), but are commonly in shallow coastal areas such as over continental shelves and lagoons to depths of 80 m (Denham et al., 2007). The great hammerhead migrates seasonally, with some populations moving poleward to cooler waters during the summer months (Denham et al., 2007).

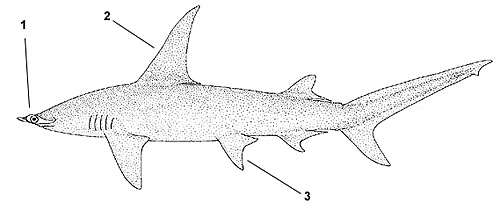

Distinguishing Characteristics

1. Anterior margin of cephalofoil straight and hammer-shaped with a prominent indentation at the midline

2. First dorsal fin tall and recurved

3. Pelvic fins are large with a prominent leading edge and a recurved rear margin

Biology

Distinctive Features

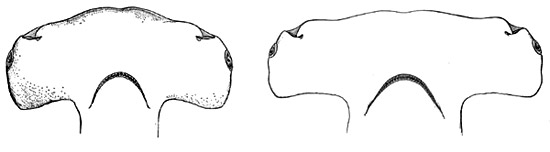

The great hammerhead is a very large shark with the characteristic hammer-shaped head from which it derives its common name. The front margin of the head is nearly straight with a shallow notch in the center in adult great hammerheads, distinguishing it from the smooth hammerhead and scalloped hammerhead (Compagno et al., 2005). The first dorsal fin is very tall with a pointed tip and is strongly falcate and recurved in shape while the second dorsal is also high with a strongly concave rear margin (Compagno et al., 2005). The origin of the first dorsal fin is opposite or slightly behind the pectoral fin axil with the free rear tip reaching to above the origin of the pelvic fins. The rear margins of the pelvic fins are concave and falcate in shape, not seen in scalloped hammerhead (S. lewini). The posterior edge of the anal fin is deeply notched.

The anterior margin of the head is more recurved in juveniles in striking contrast to the nearly straight margin seen in adults of the same species.

Currently 9 different species of hammerhead are recognized. They can be differentiated by a combination of size and the shapes of their cephalofoils. There are 4 large species: the Scalloped hammerhead, S.lewini; the recently described Carolina hammerhead, S. gilberti; the Smooth hammerhead, S. zygaena and the Great hammerhead, S. mokarran. The scalloped hammerhead (S. lewini) and Carolina hammerhead are indistinguishable in external appearance. They can only be distinguished on the basis of their different vertebral counts and genetic data. However, both can be distinguished from the other 2 large species of hammerhead by their characteristic “4-scallop” pattern of indentations at the anterior margin of the cephalofoil. The smooth hammerhead (S. zygaena) has a head that is similar in overall shape to the scalloped hammerhead but does not have the centrally placed indentation or notch that is characteristic of the scalloped hammerhead. The 5 smaller species (S. tudes, S. corona, S. media, S. tiburo and E. blochii) are unlikely to be confused with the 4 larger species.

Coloration

The dorsal surface of the great hammerhead is dark brown to light grey or even olive in color, fading to a lighter white on the underside. The fins lack conspicuous markings in adults while the apex of the second dorsal fin may appear dusky in juveniles.

Dentition

The teeth of this hammerhead are triangular and strongly serrated, but increasingly oblique toward the corners of the mouth. There are 17 teeth on either side of the 2-3 teeth at the symphysis in the upper jaw and 16 or 17 teeth on either side of the 1-3 teeth at the symphysis on the lower jaw.

Denticles

The skin is covered by dermal denticles that are closely spaced, overlapping along the front and lateral margins. Each blade is diamond-shaped and smooth along the base. There are 3-5 ridges on each blade on small specimens and as many as 5 or 6 in larger individuals. The teeth along the posterior margin are short with the median tooth slightly longer than the other teeth.

Size, Age, and Growth

As the largest of the hammerheads, the great hammerhead averages over 500 pounds (230 kg). The world record great hammerhead was caught off Sarasota, Florida (US) weighing 991 pounds (450 kg). The largest reported length of a great hammerhead is 20 feet (610 cm). Expected life span of the species is 20-30 years of age.

In waters off Australia, males reach maturity at a length of 7.4 feet (2.25 m) corresponding to a weight of 113 pounds (51 kg) and females are mature at a total length of 6.9 feet (2.10 m) corresponding to a weight of 90 pounds (41 kg) (Stevens and Lyle, 1989).

Food Habits

Great hammerheads are active predators, preying upon a wide variety of marine organisms, from invertebrates to bony fishes and sharks. They are known to prefer stingrays and other batoids when available (Compagno et al., 2005). Great hammerheads are thought to be cannibalistic, eating individuals of their own species if food is scarce (Myers et al., 2007).

Reproduction

As with all hammerheads, the species is viviparous with nutrition for the developing embryos provided through a yolk-sac placenta. Following a gestation period of approximately 11 months, birth occurs during the spring or summer in the Northern Hemisphere (Denham et al., 2007). Litters range in number from 6 to 42 pups each measuring between 50 and 70 cm total length (Compagno et al., 2005). Females breed once every two years (Stevens and Lyle, 1989).

Predators

Larger sharks will prey on juvenile and sub-adult great hammerheads. There are no major predators of the adults (Myers et al. 2007).

Parasites

Copepods found on great hammerheads include Alebion carchariae, A. elegans, Nesippus orientalis, N. crypturus, Eudactylina pollex, Kroyeria gemursa, and Nemesis atlantica.

Taxonomy

The great hammerhead was originally described as Zygaena mokarran by German naturalist Eduard Rüppell in 1837, however he changed this name to the currently valid Sphyrna mokarran later that same year. The name Sphyrnatranslates from Greek to the English language “hammer”, referring to the hammer-shaped head of this species. Synonyms used in past scientific literature include Sphyrna tudes (Valenciennes 1822), Zygaena dissimilis (Murray 1887) and Sphyrna ligo (Fraser-Brunner 1950).

There are approximately 10 related species of hammerheads throughout tropical and temperate regions including the bonnethead (Sphyrna tiburo), scalloped hammerhead (Sphyrna lewini), and smooth hammerhead (Sphyrna zygaena).

References

Compagno, L., Dando, M., & Fowler, S. (2005). A Field Guide to the Sharks of the World. London: Harper Collins Publishers Ltd.

Denham, J., Stevens, J.D., Simpfendorfer, C., Heupel, M.R., Cliff, G., Morgan, A., Graham, R., Ducrocq, M., Dulvy, N.K., Seisay, M., Asber, M., Valenti, S.V., Litvinov, F., Martins, P., Lemine Ould Sidi, M., Tous, P. & Bucal, D. 2007. Sphyrna mokarran. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2007: e.T39386A10191938.

McComb, D.M., Tricas, T.C., and S.M. Kajiura. (2009). Enhanced visual fields in hammerhead sharks. Journal of Experimental Biology 2012: 4010-4018

Myers, R.A., Baum, J.K., Shepherd, T.D., Powers, S.P. and C.H. Peterson. (2007). Cascading Effects of the Loss of Apex Predatory Sharks from a Coastal Ocean. Science 315: 1846-1850.

Snyder, D. B. & Burgess G. H. (2016). Hammerhead Sharks Family Sphyrnidae. Marine Fishes of Florida 2016: 37-38.

Stevens, J.D. and Lyle, J.M. 1989. Biology of three hammerhead sharks (Eusphyra blochii, Sphyrna mokarran and S. lewini) form Northern Australia. Australian Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research 40:129–146.

Revised by Lindsay French, Jennifer Dorrian and Gavin Naylor 2018

Original preparation by Cathleen Bester