Squalus cubensis

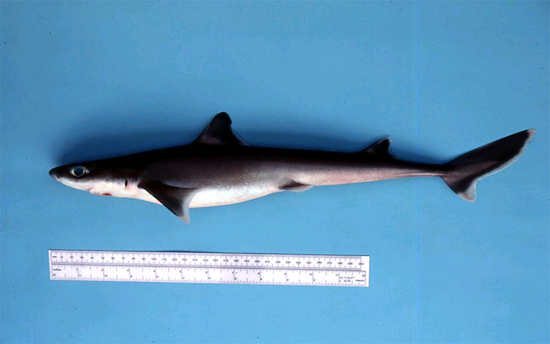

This slender, schooling shark prefers deeper, warm waters of the Western Atlantic where it eats smaller bony fish and invertebrates and can grow to around 76.2 cm (30 in) long (Compagno et al., 2005). It has large eyes set close to its pointed snout, spines at the front of each dorsal fin, and a lobed, asymmetrical caudal (tail) fin. Dark gray-brown on top and fading to white underneath, it has dark dorsal fins and light or white edges to all its fins. Despite its dorsal spines, it is considered harmless to humans because of their size and deep-sea habitat.

Order – Squaliformes

Family – Squalidae

Genus – Squalus

Species – cubensis

Common Names

- English: Cuban dogfish, puppyshark dogfish

- French: aiguillat cubain

- Portuguese: cação, Cação-bagre, Cação-de-espinho, Cação-espinhoso, Cação-olho-de-gato, Cação-prego

- Spanish: Cazón aguijón cubano, galludo, galludo cubano, parra

- Dutch: Cubaanse doornhaai

- Swedish: Cubansk pigghaj, Cubansk pighaj, Kubansk pigghaj

Importance to Humans

Cuban dogfish are fished commercially primarily in the northern Gulf of Mexico in the trawl net fishery. They are captured for their large liver due to its rich oil and vitamin content. However, it is seldom used for human consumption (Compagno et al., 2005).

Danger to Humans

Although this dogfish has dorsal fin spines that can cause painful wounds to humans, this species is considered harmless due to its small size and its preference to deep waters. There have been no unprovoked shark attacks by Cuban dogfish according to the International Shark Attack Files.

Conservation

Catch statistics are sparsely reported for the Cuban dogfish and little is known about its population status. What little data is available comes from this dogfish as bycatch of artisanal and commercial fisheries in the Caribbean region. Catches need to be monitored as deep-water fisheries are expanding throughout the world. Over fishing may well pose a threat to the Cuban dogfish in the near future. One study reported the capture of 195 Cuban dogfish in 2010 in one deep-water Gulf of Mexico longline fishery, which comprised almost 50% of shark species caught in that fishery. About 30 were thrown back dead (Hale et al., 2011).

The IUCN is a global union of states, governmental agencies, and non-governmental organizations in a partnership that assesses the conservation status of species.

> Check the status of the Cuban dogfish at the IUCN website.

Geographical Distribution

This shark resides in the subtropical western Atlantic Ocean from North Carolina to Florida in the US. It also lives in the northern Gulf of Mexico from Mexico east to Florida. Off the coast of South America, it is found off southern Brazil and Argentina, and has been recently observed off Isla Fuerte, Columbia. This dogfish also inhabits Caribbean waters near Cuba, Hispaniola (Dominican Republic and Haiti) (Orozco-Velasquez & Gomez-Delgado 2016).

Habitat

Indigenous to deep waters, the Cuban dogfish prefers warm to tropical waters. It is found close to the bottom in large dense schools, primarily along the outer Continental Shelf and uppermost slopes at depths from approximately 60-731 m (200-2400 ft) (Compagno et al. 2005, Brooks et al., 2015).

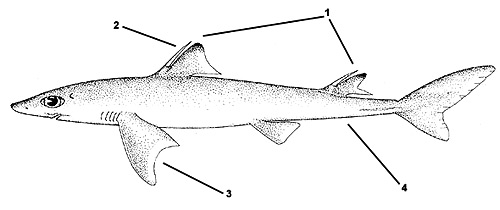

Distinguishing Characteristics

1. Two dorsal fins with large spines

2. First dorsal spine about as long as dorsal fin base

3. Pectoral fins are falcate with angular free rear tips and concave posterior margins

4. Anal fin absent

Biology

Distinctive Features

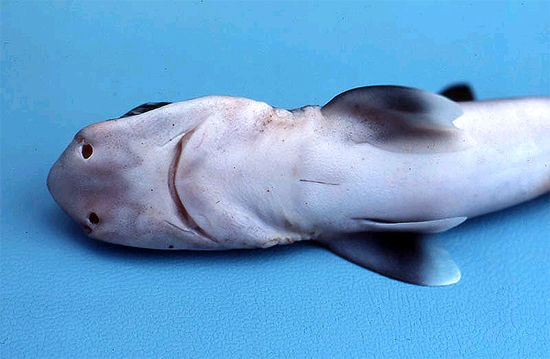

This shark has a slender body with subangular snout. The eyes are closer to the tip of the snout than the first gill slit. It has long un-grooved spines at the front edge of both dorsal fins. The first dorsal spine originates in front of pectoral fin rear tips and is approximately as long as the base of the first dorsal fin. The second dorsal fin is markedly smaller than the first. The pectoral fins are falcate, or curved inward, and have strongly concave posterior margins. The anal fin is absent, as in all dogfish. The caudal fin is narrowly lobed and moderately long with a long ventral lobe. There is no subterminal notch on the caudal fin. There is a well-developed upper precaudal pit and lateral keels on the caudal peduncle (Compagno et al., 2005).

Due to their limited distribution and ease of recognition, the Cuban dogfish is rarely confused with other species. However, it may be sometimes confused with the longnose spurdog (Squalus blainvillei). The longnose spurdog has pectoral fins with rounded free rear tips while the Cuban dogfish’s pectoral fins have pointed free rear tips.

The spiny dogfish (Squalus acanthias) and the roughskin dogfish (Cirrhigaleus asper) have a first dorsal fin originating over or posterior to the free rear tips of the pectoral fins. The Cuban dogfish has a first dorsal fin that originates anterior to the free rear tips of the pectoral fins.

Coloration

The dorsal surface is gray-brown in color fading to a white ventral surface. There are no white spots on the body of this species. The tips of the two dorsal fins are dark and all fins have lightly colored to white edges (Compagno et al., 2005).

Dentition

Cuban dogfish teeth are strongly oblique, smooth-edged cusps with a strong notch on their outer margins forming a nearly continuous cutting edge. The teeth are similar in both the upper and lower jaws with approximately 26 teeth in each jaw (Sadowsky & Moreira 1981).

Denticles

The denticles located laterally along the trunk of the Cuban dogfish are small, unicuspidate, and lanceolate with a strong central ridge that divides anteriorly into two or three ridges with broad extensions on either side of the central ridge (Bigelow & Schroeder 1957).

Size, Age & Growth

The maximum reported size of the Cuban dogfish is approximately 110 cm (43.3 in) total length with the average adult size about 75 cm (29.5 in) total length. Sexual maturity is obtained at lengths of 50 cm (19.7 inches) (Compagno et al., 2005). These estimates have been called into question by Jones et al. (2013). Their recorded sizes usually came to 54cm between different studies.

Food Habits

Although very little is known about the food habits of the Cuban dogfish, it is believed that it feeds on small fish and benthic invertebrates, such as squid and shrimp (Churchill et al., 2015).

Reproduction

Cuban dogfish are ovoviviparous. Each litter consists of approximately 2 pups (Jones et al. 2013, Tomita et al. 2016). Young Cuban dogfish reside in shallower waters along the Continental shelf rather than in the deeper water where mature Cuban dogfish live (Compagno et al., 2005). It is suggested that breeding does not occur at any particular time of the year, which is to be expected for deep-water chondrichthyans (Jones et al., 2013).

Predators

Potential predators include marine mammals and large fish including other sharks.

Parasites

Cuban dogfish can have an unusual, huge 4.8 cm (1.89 in) isopod parasite (Lironeca splendida) that lives in its buccal cavity (Sadowsky & Moreira 1981). Shipley, Talwar et al. (2017) recorded an isopod of the Aega sp. removed from the abdomen of one Cuban dogfish and another isopod of the Aegaphales sp. removed from the clasper of a second Cuban dogfish. The effect of these parasites on the shark’s overall health is unclear.

Taxonomy

The Cuban dogfish was originally described by Howell Riviero in 1936 as Squalus cubensis. It is a member of the Squalidae to which the dogfish sharks belong. The genus name Squalus is derived from the Latin “squalidus” meaning pale and weak. There are no known synonyms used to refer to this species in previous scientific literature.

Revised by: Tyler Bowling and Kiersten Meigs 2020

Prepared by: Cathleen Bester

References

- Bigelow, H.B. and W.C. Schroeder (1957). A study of the sharks of the suborder Squaloidea. Bull.Mus.Comp.Zool.Harv.Univ., 117(1):150 p.

- Brooks, E. J., Brooks, A. M., Williams, S., Jordan, L. K., Abercrombie, D., Chapman, D. D., … & Grubbs, R. D. (2015). First description of deep-water elasmobranch assemblages in the Exuma Sound, The Bahamas. Deep Sea Research Part II: Topical Studies in Oceanography, 115, 81-91.

- Churchill, D. A., Heithaus, M. R., Vaudo, J. J., Grubbs, R. D., Gastrich, K., & Castro, J. I. (2015). Trophic interactions of common elasmobranchs in deep-sea communities of the Gulf of Mexico revealed through stable isotope and stomach content analysis. Deep Sea Research Part II: Topical Studies in Oceanography, 115, 92-102.

- Compagno, L, Dando, M, Fowler, S. (2005). Shark of the World. HarperCollins.

- Dillon, E. M., Norris, R. D., & Dea, A. O. (2017). Dermal denticles as a tool to reconstruct shark communities. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 566, 117-134.

- Hale, L. F., Gulak, S. J., Carlson, J. K., & Napier, A. M. (2011). Characterization of the shark bottom longline fishery, 2010.

- Jones, L. M., Driggers III, W. B., Hoffmayer, E. R., Hannan, K. M., & Mathers, A. N. (2013). Reproductive biology of the Cuban dogfish in the northern Gulf of Mexico. Marine and Coastal Fisheries, 5(1), 152-158.

- Orozco-Velasquez, D. M., & Gómez-Delgado, F. (2016). New record of Squalus cubensis Howell Rivero, 1936 (Chondrichthyes, Squalidae) in Colombia. Universitas Scientiarum, 21(2), 159-166.

- Sadowsky, V., & Moreira, P. S. (1981). Occurrence of Squalus cubensis Rivero, 1936, in the Western South Atlantic Ocean, and incidence of its parasitic isopod Lironeca splendida sp. n. Studies on Neotropical Fauna and Environment, 16(3), 137-150.

- Shipley, O. N., Howey, L. A., Tolentino, E. R., Jordan, L. K., & Brooks, E. J. (2017). Novel techniques and insights into the deployment of pop-up satellite archival tags on a small-bodied deep-water chondrichthyan. Deep Sea Research Part I: Oceanographic Research Papers, 119, 81-90.

- Shipley, O. N., Olin, J. A., Polunin, N. V., Sweeting, C. J., Newman, S. P., Brooks, E. J., … & Hussey, N. E. (2017). Polar compounds preclude mathematical lipid correction of carbon stable isotopes in deep-water sharks. Journal of experimental marine biology and ecology, 494, 69-74.

- Shipley, O., Talwar, B., Grubbs, D., & Brooks, E. (2017). Isopods present on deep-water sharks Squalus cubensis and Heptranchias perlo from The Bahamas. Marine Biodiversity, 47(3), 789-790.

- Tomita, T., Cotton, C. F., & Toda, M. (2016). Ultrasound and physical models shed light on the respiratory system of embryonic dogfishes. Zoology, 119(1), 36-41.