Squatina californica

This flattened benthic shark ambushes prey from beneath the sand. Unlike rays, angelsharks have tubular tails with asymmetrical caudal (tail) fin and lack a venomous spine.

Order – Squatiniformes

Family – Squatinidae

Genus – Squatina

Species – californica

Common Names

- English: angelshark, Pacific angelshark, monk fish

- Dutch: Pacifische zee-engel

- Finnish: Kalifornianmerienkeli

- French: ange de mer du Pacifique

- German: Pazifischer Meerengel

- Norwegian: Californisk havengel

- Polish: raszpla Kalifornijska

- Spanish: angelote, tiburón angel, pez ángel del Pacífico

- Swedish: Kalifornisk havsängel

Importance to Humans

In the mid-1980s, they became part of a developing fishery. It was commercially caught with gillnets and recreationally caught by sport spearfishers. However, there is currently a moratorium.

Danger to Humans

Although this shark is a bottom dweller and appears harmless, it possesses powerful jaws. Though there have never been any confirmed attacks, divers should still use caution.

Conservation

Only recently has there been a fishery for these animals off southern California. Currently, there is a large regulated trawl and gillnet fishery. Commercial catch data show that landings of this species went from 166 kg (366 lb.) in 1977 to over 310,000 kg (700,000 lb.) in 1984. However, due to its slow reproductive rate and growth as well as late maturation, this species is vulnerable to overfishing. Currently, the gillnet fishery off California is closed until further notice due to the depletion of the population. A continued fishery would pose a serious threat to this species in U.S. waters. The Pacific angelshark is currently assessed as “Near Threatened” by the IUCN (Fowler et al., 2005; Leet et al., 2001).

> Check the status of the Pacific angelshark at the IUCN website.

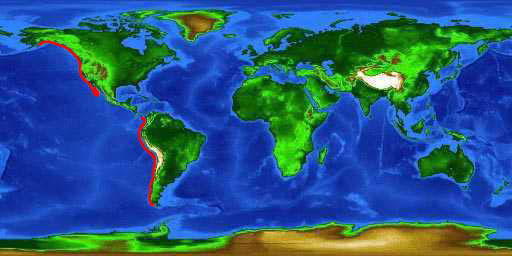

Geographical Distribution

The eastern Pacific Ocean from southeastern Alaska to the Gulf of California and Costa Rica to southern Chile ((Bustamante et al. 2014; Leet et al. 1992, 2001; Natanson and Cailliet, 1986, 1990). Off the coast of California, it is seen occasionally while between Oregon and southern Alaska it is uncommon to rare.

Habitat

This shark, in contrast to many other species, is benthic (bottom dweller). It buries itself in sand or mud bottoms during the day, coming out to actively search for food at night. It is often found on the continental shelf and littoral areas, and sometimes near rock canyons and kelp forests (Feder et al. 1974; Ebert, 2003). Off the coast of California, this angelshark can be found typically at depths of 100 m (328 ft.). The adults have high site fidelity, often resting in the same spot every day (Standora and Nelson, 1977).

Biology

Distinctive Features

The Pacific angelshark is dorsoventrally flattened with a terminal mouth at the tip of the snout. The pectoral fins are broad and separated from the head. This characteristic distinguishes angelsharks from the rays, whose pectoral fins are completely attached to the sides of its head. Eyes and spiracles are located on the top of the head, with five pairs of gill slits extending from the side of the head to under the throat. The gill slits of rays are located ventrally. Fleshy nasal barbels and flaps are also located at the snout. This shark lacks anal fins and dorsal fin spines. The two dorsal fins are located on the rear of the body near the base of the tubular tail. The caudal fin is well developed with a longer lower lobe than the upper lobe (Compagno, 2001; Ebert, 2003).

Coloration

This species may occasionally be dark brown or grey, splotched with shades of brown and black. These coloration patterns allow the shark to camouflage with mud and sandy bottoms. The ventral side is white and extends to the periphery of the mouth and fins (Compagno et al., 2005).

Dentition

Pointed and conical teeth with smooth edges and broad bases. The upper and lower jaws have 14-18 rows of teeth with large gaps at each symphysis (Ebert, 2003).

Size, Age, and Growth

The maximum length is 118 cm (3.9 ft.) for males and 152 (4.9 ft.) for females, with a maximum, reported age of 35 years (Ebert, 2003). Size of maturity appears to vary by location but usually occurs for both sexes between 76-112 cm, taking anywhere from 8-13 years to mature (Cailliet et al. 1992; Cortes, 2002; Natanson and Cailliet 1986; Romero-Caicedo et al., 2016)

Food Habits

Bony fishes including croakers, halibut, as well as small elasmobranchs. It is also known to consume invertebrates such as crustaceans and mollusks (Ebert, 2003).

During daylight hours, the Pacific angelshark camouflages itself in the sand waiting for potential prey. When a prey item comes within reach, the angelshark ambushes the prey, snatching it up with powerful jaws. After feeding, the shark settles back into the bottom substrate, awaiting another prey item. Feeding usually occurs during nighttime hours when the angelshark cruises over the bottom in search of fish and invertebrates such as squids, octopus and crustaceans (Ebert, 2003; Fouts, and Nelson, 1999).

Reproduction

There is little known about the mating behavior of the Pacific angelshark other than that it probably occurs in early summer. Reproduction takes place via aplacental viviparity. The gestation period is approximately 10 months with birth occurring from March to June. Litter size ranges from 1-13, with the pups measuring 25 cm (9.8 in.) at birth (Natanson and Cailliet, 1986; Ebert, 2006).

Predators

Larger sharks, including white sharks (Carcharodon carcharias) as well as northern elephant seals (Mirounga angustirostris) (Ebert, 2003; Sinclair, 1994).

Taxonomy

The Pacific angelshark was described by the first curator of Ichthyology at the California Academy of Sciences, William O. Ayres, in 1859 as Squatina californica. The genus name Squatina is derived from Latin, meaning “a kind of shark”. Other references to this species which may be questionable include Squatina armata Philippi, 1887, Rhina armata Philippi, 1887, and Rhina philippi Garman, 1913. Approximately 15 species of angelshark in the family Squatiniformes which have been described, although there are species existing that have yet to be described.

Revised by: Tyler Bowling 2019

Prepared by: Cathleen Bester

References

- Bustamante, C., Vargas-Caro, C. and Bennett, M.B. 2014. Not all fish are equal: functional biodiversity of cartilaginous fishes (Elasmobrnachii and Holocephali) in Chile. Journal of Fish Biology 85(5): 1617-1633

- Compagno, L.J.V. 2002. Sharks of the World: An Annotated and Illustrated Catalogue of Shark Species Known to Date (Volume 2). Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization. pp. 144–145.

- Compagno, L.J.V.; Dando, M. & Fowler, S. 2005. Sharks of the World. Princeton University Press. pp. 140–141.

- Compagno, L.J.V. 1984. FAO Species Catalogue. Vol 4: Sharks of the World. An annotated and illustrated catalogue of shark species known to date. Part 1: Hexanchiformes to Lamniformes. Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations, Rome.

- Cailliet, G.M., Mollet, H.F., Pittinger, G.G., Bedford, D. and Natanson, L.J. 1992. Growth and demography of the Pacific angel shark (Squatina californica), based upon tag returns off California. Australian Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research 43: 1313–1330.

- Cortes, E. 2002. Incorporating uncertainty into demographic modeling: application to shark populations and their conservation. Conservation Biology 16: 1048–1062.

- Deets, G.B. & Dojiri, M.1989. Three species of Trebius Krøyer, 1838 (Copepoda: Siphonostomatoida) parasitic on Pacific elasmobranchs. Systematic Parasitology. 13 (2): 81–101.

- Ebert, D.A. 2003. Sharks, Rays and Chimaeras of California. University of California Press, Berkeley.

- Feder, H.M., Turner, C.H. and Limbaugh, C. 1974. Observations on fishes associated with kelp beds in southern California. California Fish and Game Fish Bulletin 160: 44.

- Fouts, W.R. & Nelson, D.R. 1999. Prey Capture by the Pacific Angel Shark, Squatina californica: Visually Mediated Strikes and Ambush-Site Characteristics. Copeia. American Society of Ichthyologists and Herpetologists.

- Fowler, S.L.; Cavanagh, R.D.; Camhi, M.; Burgess, G.H.; Cailliet, G.M.; Fordham, S.V.; Simpfendorfer, C.A. & Musick, J.A. 2005. Sharks, Rays and Chimaeras: The Status of the Chondrichthyan Fishes. International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources. pp. 233–234.

- Jameson, A.P. 1931. Notes on Californian Myxosporidia. The Journal of Parasitology. The American Society of Parasitologists. 18 (2): 59–68.

- Jensen, K. 2001. Four New Genera and Five New Species of Lecanicephalideans (Cestoda: Lecanicephalidea) From Elasmobranchs in the Gulf of California, Mexico. Journal of Parasitology. 87 (4): 845–861.

- Leet, W.S.; Dewees, C.M.; Klingbeil, R.; Larson, E.J., eds. 2001. Pacific Angel Shark. California’s Living Resources: A Status Report (fourth ed.). ANR Publications. pp. 248&ndash, 251.

- Leet, W.S., Dewees, C.M., Klingbeil, R. and Larson, E.J. 2001. California’s Living Marine Resources: A Status Report. The Resources Agency, California Department of Fish and Game.

- Leet, W.S., Dews, C.M. and Hague, C.W. 1992. California’s Living Marine Resources and Their Utilization.

- Moser, M. & Anderson, S. 1977. An intrauterine leech infection: Branchellion lobata Moore, 1952 (Piscicolidae) in the Pacific angel shark (Squatina californica) from California. Canadian Journal of Zoology. 55 (4): 759–760.

- Natanson, L.J. and Cailliet, G.M. 1986. Reproduction and development of the Pacific angel shark, Squatina californica, off Santa Barbara, California. Copeia 1986(4): 987–994.

- Natanson, L.J. and Cailliet, G.M. 1990. Vertebral growth zone deposition in Pacific angel sharks. Copeia 1990(4): 1133–1145

- Romero-Caicedo, A.F., Galván-Magaña, F., Hernández-Herrera, A. and Carrera-Fernández, M. 2016. Reproductive parameters of the Pacific angel shark Squatina californica (Selachii: Squatinidae). Journal of Fish Biology Early View, DOI:10.1111/jfb.12920.

- Sinclair, E.H. 1994. Prey of juvenile northern elephant seals (Mirounga angustirostris) in the Southern California Bight. Marine Mammal Science. 10 (2): 230–239.

- Standora, E.A. and Nelson, D.R. 1977. A telemetric study of the behavior of free-swimming Pacific angel sharks, Squatina californica. Bulletin of the Southern California Academy of Sciences 76: 193-201