Zebra Shark

Stegostoma fasciatum

This mollusk crunching coastal carpetshark was misidentified for years by taxonomists. Due to the black and white stripes of the pups eventually turning to spotted adults, the two different life stages were thought to be differing species. Zebra sharks are popular attractions for eco-tourism and public aquariums.

Order – Orectolobiformes

Family – Stegostomatidae

Genus – Stegostoma

Species – fasciatum

Common Names

- English: zebra shark, leopard shark, and variegated shark

- Afrikaans: sebrahaai

- Arabic: thalab al bahar

- Bikol: butanding

- Carolinian: nirééré, wolaaliy

- Danish: zebrahaj

- Dutch: zebrahaai

- French: requin tigre, requin zèbre

- Gela: bagea oneone

- German: zebrahai, pazifischer Zebrahai

- Gujarati: magara, musia, shinawala, shinvala

- Khmer: chkuot, chlarm

- Japanese: torafu zame, torafuzame

- Malay: yu chechak, yYu chechok, yu kebut, yu tokeh, cucut poto, cucut tekeh, poochasurav, zebra sravu

- Maldivian: hitha miyaru

- Marathi: mushi, shinavla

- Persian: kooseh-e-Goor-e-khari

- Polish: rekin brodaty

- Portuguese: tubarão-zebra

- Samoan: moemoeao, ta’aneva

- Sindhi: mangra

- Spanish: tiburón acebrado

- Somali: farluuq shabeellow

- Swedish: sebrahaj

- Tagalog: pating

- Tamil: coruhgun-sorrah, corungum sorrah, korangum sorrah, komarasi-sorrah

- Telugu: corootoolti-sorrah, komrasi, komarasi, orookoolti-sorrah, pollee makum, potrava

- Thai: chalarm-sue-dao

- Vietnamese: cá nhám nhu mí

- Visayan: talakitiki

Importance to Humans

This shark is of only minor interest to commercial fisheries although it is considered a gamefish recreationally. Often taken as bycatch in drift nets, the meat is occasionally sold, and the fins are dried and sold in the Asian shark fin market (White et al. 2006).

Zebra sharks adapt well to captivity, making for an easy care attraction at many aquariums around the globe. Captive breeding programs have been very successful, adding great numbers to aquaria stock and reintroduction to the wild. They are a big draw for recreational divers across their range (Anderson, 2002).

Danger to Humans

They are generally harmless to humans however, they may bite if provoked. There has been one documented unprovoked attack on a human according to the International Shark Attack File, however, this attack resulted in no injuries.

Conservation

ICUN lists the species as “Endangered”. Declines in populations are due to inshore fishery activities and coral reef habitat loss (Pillans and Simpfendorfer 2003). In Australia, it is considered “Least Concern” due to its abnormal abundance, likely due to the many protected reef systems.

> Check the status of the zebra sharks at the IUCN website.

The IUCN is a global union of states, governmental agencies, and non-governmental organizations in a partnership that assesses the conservation status of species.

Geographical Distribution

The zebra shark resides along continental and insular shelves in the Indo-West Pacific Ocean, the Red Sea, East Africa, Japan, and New South Wales (Australia), (Compagno, 2001). Genetic data has revealed two distinct subpopulations: The Indian- Southeast Asian, and the Eastern Indonesian-Oceania subgroup (Dudgeon et al. 2009). This is likely due to a strong site fidelity to the reefs individuals reside at. Though individuals do migrate seasonally within a limited range (Dudgeon et al. 2013).

Habitat

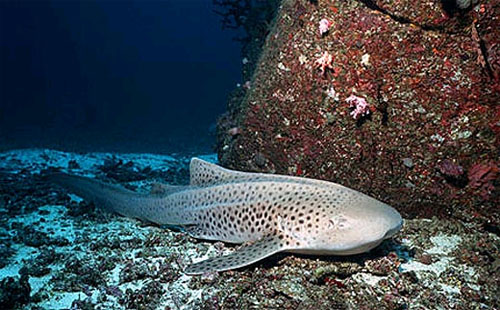

A tropical and subtropical, inshore species, zebra sharks lives on sand, rock reefs, and coral bottoms, 0-62 m (0-207 ft.) deep (Compagno, 2001). Usually sluggish during daylight hours, becoming active to hunt nocturnally. It is often observed sitting on the bottom in close proximity to coral reefs. This species has been recorded in marine and brackish waters as well as in freshwater habitats.

Biology

Distinctive Features

The zebra shark has a moderately stout, cylindrical body with 5 prominent ridges running along the dorsal surface and flanks (Compagno, 2001). The head has 5 small gill slits with the last 3 located behind the origin of the pectoral fins. The nostrils are close to the front of the rounded snout which has short barbels (Randall and Hoover, 1995). The spiracles are as large as the eyes. The large pectoral fins are broadly rounded. The first dorsal fin is larger than the second, with the rear tip of the first dorsal fin close to the origin of the second. The caudal fin is almost as long as the main body (Compagno, 2001).

Coloration

Adults are yellow-brown with dark brown spots while the young (smaller than 70 cm (2.2 ft.)) are dark in color with white spots and stripes, fading to a pale ventral surface. The juveniles’ stripes are what give this species its common name of zebra shark. Additionally the adults have longitudinal ridges along the body, which are absent in juveniles (Compagno, 2001).

Dentition

The dentition is similar in both jaws, with 28-33 teeth in the upper jaw and 22-32 in the lower. There is a large central cusp bordered by two smaller ones (Compagno, 2001).

Size, Age & Growth

The maximum reported size is 246 cm (8 ft.) (Dudgeon et al. 2008). Males reach sexual maturity at 150–180 cm (4.9–5.9 ft), and females at 170 cm (5.6 ft) long (Compagno, 2001). The lifespan of the zebra shark is believed to be 25-30 years.

Food Habits

These nocturnal hunters feed primarily on mollusks, crustaceans, small bony fishes, and even sea snakes. Sucking their prey up with powerful buccal cavity muscles. It squirms into narrow crevices and channels in reefs searching for prey (Compagno, 2001).

Reproduction

The species is oviparous, releasing egg cases into the environment, which anchor to the bottom substrate with hair-like fibers. Egg cases are large, dark brown or purplish black, with longitudinal striations, measuring 17x8x5 cm (6.7×3.1×2 in.). When the young emerge, they measure approximately 20-36 cm (7.9-10 in.). Individuals in captivity have been known to lay eggs annually for up for 3 months at a time. Producing 40-80 eggs per year. Zebra sharks are known to reproduce asexually as well, via parthenogenesis (the development of an unfertilized egg, making the offspring essentially a clone of the mother) (Robinson et al. 2011)

Predators

Larger bony fish, sharks, as well as marine mammals.

Parasites

The flat worm Pseudolacistorhynchus nanus sp. nov. (Beveridge and Justine, 2007), the marine leech Branchellion torpedinis (Marancik et al., 2012) and 3 species of tapeworm (Pedibothrium spp.) (Caira, 1992) are documented to parasitize zebra sharks.

Taxonomy

Hermann originally described the zebra shark as Squalus fasciatus in 1783. However that name was later changed to the currently valid Stegostoma fasciatum (Hermann 1783). The genus name, Stegostoma, is derived from the Greek stego meaning ‘cover’ and stoma meaning ‘mouth’. It is the only species within its genus. Synonyms referring to this species in past scientific literature include Squalus longicaudus Gmelin 1789, Scyllia quinquecornuatum Van Hasselt 1823, Scyllium heptagonum Rüppell 1837, Stegostoma carinatum Blyth 1847, Squalus cirrosus Gronow 1854, Stegostoma varius Garmin 1913, Stegostoma varium Garmin 1913, Stegastoma varium Graman 1923, and Stegostoma tigrinum naucum Whitley 1939.

Revised by: Tyler Bowling 2019

Prepared by: Cathleen Bester

References:

- Anderson, R.C. 2002. Elasmobranchs as a recreational resource. In: S.L. Fowler, T.M. Reed & F.A. Dipper (ed.), Elasmobranch Biodiversity, Conservation and Management: Proceedings of the International Seminar and Workshop. Sabah, Malaysia. July 1997. pp. 46–51. IUCN SSC Shark Specialist Group. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge, UK.

- Beveridge, I. and Justine, J.L., 2007. Pseudolacistorhynchusnanus N. SP.(Cestoda: Trypanorhyncha) Parasitic In the spiral valve Of the zebra Shark, Stegostoma Fasciatum (Hermann, 1783). Transactions of the Royal Society of South Australia, 131(2), pp.175-181.

- Caira, J.N., 1992. Verification of multiple species of Pedibothrium in the Atlantic nurse shark with comments on the Australasian members of the genus. The Journal of parasitology, pp.289-308.

- Compagno, L.J.V. 2001. Sharks of the world. An annotated and illustrated catalogue of shark species known to date. Vol. 2. Bullhead, mackeral and carpet sharks (Heterodontiformes, Lamniformes and Orectolobiformes). FAO species catalogue for fisheries purposes. No. 1. Vol. 2. FAO, Rome.

- Dudgeon, C.L., Broderick, D. and Ovenden, J.R. 2009. IUCN classification zones concord with, but underestimate, the population genetic structure of the zebra shark Stegostoma fasciatum in the Indo-West Pacific. Molecular Ecology 18(2): 248-261.

- Dudgeon C.L., Lanyon, J.M. and Semmens, J.M. 2013. Seasonality and site-fidelity of the zebra shark Stegostoma fasciatum in southeast Queensland, Australia. Animal Behaviour 85: 471-481.

- Dudgeon, C.L, Noad, M.J. and Lanyon, J.M. 2008. Abundance and demography of a seasonal aggregation of zebra sharks Stegostoma fasciatum. Marine Ecology-Progress Series 368: 269-281.

- Marancik, D.P., Leary, J.H., Fast, M.M., Flajnik, M.F. and Camus, A.C., 2012. Humoral response of captive zebra sharks Stegostoma fasciatum to salivary gland proteins of the leech Branchellion torpedinis. Fish & shellfish immunology, 33(4), pp.1000-1007.

- Pillans, R. and Simpfendorfer, C. 2003. Stegostoma fasciatum. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2003.

- Randall, J.E. & Hoover, J.P., 1995. Coastal Fishes of Oman. University of Hawaii Press. p. 20. ISBN 0-8248-1808-3.

- Robinson, D.P., Baverstock, W., Al‐Jaru, A., Hyland, K. and Khazanehdari, K.A., 2011. Annually recurring parthenogenesis in a zebra shark Stegostoma fasciatum. Journal of Fish Biology, 79(5), pp.1376-1382.

- White, W.T., Last, P.R., Stevens, J.D., Yearsley, G.K., Fahmi and Dharmadi. 2006. Economically Important Sharks and Rays of Indonesia. Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research, Canberra, Australia.