Leopard Shark

Triakis semifasciata

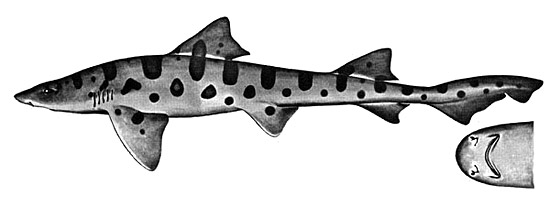

This long, slim shark likes the sandy bottoms of bays or estuaries in the eastern Pacific Ocean. It has a broad, short snout, triangular fins, and a notched, asymmetrical caudal (tail) fin. On the dorsal side, it exhibits a silver or bronzed-gray coloration, fading to white underneath, with distinct black saddle marks on its back and sides, as well as extending out onto its fins (Compagno, 2005). Generally, this shark can be found to be between 20 and 50 inches long but can grow up to 6 feet long, specializing on a diet of invertebrates and small fish. Because of the high mercury content of its flesh, there are warnings about consuming this shark (Davis et. al, 2002).

Order: Carcharhiniformes

Family: Triakidae

Genus: Triakis

Species: semifasciata

Common Names

- English: leopard shark, leopard catshark

- Dutch: luipaardhaai

- Finnish: leopardihai

- French: virli léopard

- German: leopardhai

- Portuguese: turbarão-leopardo

- Spanish (Mexico): tiburón leopardo

- Spanish (Spain): tollo leopard

Importance to Humans

Commercial and sport fishermen harvest the leopard shark (Compagno, 2005). The shark is used primarily as a food source and is sold both fresh and frozen.

Danger to Humans

The leopard shark poses virtually no danger to humans. The International Shark Attack File has a single report of an incident involving a human and a leopard shark. This incident did not reportedly cause any significant damage to the victim, and no bite was involved. However, leopard sharks do contain high levels of mercury and should not be consumed regularly, as per the warnings of the California Department of Fish & Game.

Conservation

Due to the relatively late age of first reproduction, the slow growth rate, and the low reproduction rate, the leopard shark is potentially threatened by over-fishing (Compagno, 2005). However, the shark is not currently listed as an endangered or threatened species. Management of this species in recent years is thought to have protected the core population of this species in waters off California and Oregon (US) (Cailliet, 1992). The status of stocks off Mexico is currently unknown.

> Check the status of the leopard shark at the IUCN website.

The leopard shark is considered to be at “Least Concern” by the World Conservation Union (IUCN). The IUCN is a global union of states, governmental agencies, and non-governmental organizations in a partnership that assesses the conservation status of species.

Geographical Distribution

Leopard sharks have a relatively narrow range, found in the Eastern Pacific Ocean from Oregon to the Gulf of California in Mexico (Compagno, 2005). Large populations occur in San Francisco Bay, and other large estuaries (Davis et. al, 2002; Smith and Abramson, 1990).

Habitat

The leopard shark is most commonly found in sandy or muddy bays and estuaries either at or near the bottom. The shark is most commonly encountered in 20 feet (6.1 meters) of water or less but has been sighted up to 300 feet (91.4 meters) deep. Leopard sharks seem to prefer cool and warm temperate waters (Compagno, 2005).

Biology

Distinctive Features

The leopard shark has a relatively broad and short snout. The prominent rounded dorsal fin of this shark originates over the inner margins of its pectoral fins. The second dorsal fin is pointed and averages about three-quarters the size of the first dorsal fin. The anal fin is diminutive in comparison to the leopard shark’s second dorsal fin. The pectoral fins of the leopard shark are rather broad and roughly triangular in shape. The upper lobe of the tail is notched and elongated.

The leopard shark could possibly be mistaken for the swell shark (Cephaloscyllium ventriosum), which is reddish-brown and has a flattened head.

Research has indicated that the erythrocytes (red blood cells) of the leopard shark are more diminutive and numerous than those of its relatives, the brown smooth-hound (Mustelus henlei) and the gray smoothhound (Mustelus californicus). This could theoretically provide the leopard shark with an edge over its chief competitors in estuarine environments by allowing the leopard shark to more easily absorb oxygen from the water (Lai et. al, 1990).

The leopard shark is a strong swimmer and it often forms large nomadic schools that sometimes include brown smooth-hounds (Mustelus henlei), gray smooth-hounds (Mustelus californicus), and spiny dogfish (Squalus acanthias) (Compagno, 2005).

Coloration

The leopard shark is conspicuously covered with dark saddles and splotches. The dorsal surface of the animal varies in coloration from silver to a bronzed gray. The ventral surface of the animal is lighter and sometimes white (Compagno, 2005).

Dentition

Leopard sharks produce tooth sets that form overlapping ridges between different tooth rows. The resulting effect is a large flattened and ridged surface on the upper and lower jaws. This type of dentition is often referred to as “pavement-toothed” (Motta, 2001; Vennemann, 2001).

Size, Age, and Growth

Leopard sharks can reach lengths of up to 7 ft (2.13 m), but it is rare to find an individual larger than 6 ft (1.83 m). The average size of an adult leopard shark is between 50 and 60 inches (120cm to 150 cm). Pups are born at a size of 8 to 9 inches (0.20 to 0.23 m). The sharks reach maturity at a size of 3 to 3.5 ft (0.91 to 1.07 m) (Compagno, 2005).

Food Habits

Leopard sharks feed primarily on benthic invertebrates and small fish (Compagno, 2005). Their diet includes invertebrates such as crabs, shrimp, octopi, fat innkeeper worms (Urechis caupo), clam siphons, and fish such as midshipmen, sanddabs, shiner perch, bat rays, smoothhounds, and a variety of fish eggs (Ebert, 2005; Talent, 1976). Leopard sharks have been known to mutilate their prey, taking only parts of the animals they ingest, leaving the rest. For example, a number of clam siphons have been found in multiple specimens of leopard shark (Talent, 1976). However, a body of a consumed clam has not been reported to be found.

Reproduction

Female leopard sharks are ovoviviparous and can produce litters of 4 to 29 pups (Compagno, 2005). The gestation period of the shark is between ten and twelve months, and birth usually occurs between April and May (Hight, 2007).

Predators

Marine mammals prey upon young leopard sharks, and both juveniles and adults are vulnerable to large fish, including the white shark (Carcharodon carcharias).

Taxonomy

Girard first documented the leopard shark as Triakis semifasciatum in 1855. Since then, the species name has been modified to semifasciata. The genus Triakis is derived from the Greek word “triakis” translated as three pointed, referring to this shark’s three pointed teeth, while the species name semifasciata means half-banded, describing the distinctive markings found on this shark.

Revised by Tyler Bowling 2020

Prepared by: Bryan Delius

References

- Cailliet, G. 1992. Demography of the central California population of the Leopard Shark (Triakis semifasciata). Marine and Freshwater Research, 43(1), 183.

- Compagno, L., Dando, M., & Fowler, S. 2005. A field guide to the Sharks of the world. London: Collins.

- Davis, J., May, M., Greenfield, B., Fairey, R., Roberts, C., Ichikawa, G., Stoelting, M., Becker, J. and Tjeerdema, R. 2002. Contaminant concentrations in sport fish from San Francisco Bay, 1997. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 44(10), pp. 1117-1129.

- Ebert, D. A., and Ebert, T. B. 2005. Reproduction, diet, and habitat use of leopard sharks, Triakis semifasciata, in Humboldt Bay, California. Marine and Freshwater Research 56(8), 1089-1098.

- Hight, B. V., and Lowe, C. G. 2007. Elevated body temperatures of adult female leopard sharks, Triakis semifasciata, while aggregating in shallow nearshore embayments: Evidence for behavioral thermoregulation? Journal of Experimental Biology and Marine Ecology 352, 114-128.

- Lai, N. C., Graham, J. B., and Burnett, L. 1990. Blood respiratory properties and the effect of swimming on blood gas transport in the leopard shark Triakis semifasciata. Journal of Experimental Biology 151, 161-173.

- Motta, P. J., Wilga, C. D. 2001. Advances in the study of feeding behaviors, mechanisms, and mechanics of sharks. Environmental Biology of Fishes 60, 131-156.

- Smith, S. E., and Abramson, N. J. 1990. Leopard shark Triakis semifasciata distribution, mortality rate, yield, and stock replenishment estimates based on a tagging study in San Francisco Bay. US National Marine Fisheries Service Fishery Bulletin 88, 371-81.

- Talent, L.G. 1976. Food habits of the leopard shark, Triakis semifasciata, in Elkhorn Slough, Monterey Bay, California. California Fish and Game 62(4), 286-298.

- Vennemann, T., Hegner, E. Cliff, G. & Benz, G. 2001. Isotopic composition of recent shark teeth as a proxy for environmental conditions. Geochimica et Cos