Swordfish

Xiphias gladius

This migratory billfish can grow to 177 inches long, from the tip of its slender bill to the end of its crescent caudal (tail) fin. It is a dark brown black above, fading to a lighter shade underneath, and its first dorsal and anal fins are significantly more pronounced and curved than the secondary ones. Adults have no scales anymore, or teeth in their jaws, probably eating their prey whole after striking it with the strong bill. Swordfish have a high tolerance for varying water temperature, partially because of a special bundle of tissue that helps to insulate their brains.

Order – Perciformes

Family – Xiphiidae

Genus – Xiphias

Species – gladius

Common Names

English language common names include swordfish, broadbill, broadbill swordfish, and sword fish. Other common names include agulha (Portuguese), albacora (Spanish), babljan (Serbian), dugso (Bikol), emperador (Spanish), espada (Portuguese), espadarte (Portuguese), espadon (French), haku (Niuean), jaglun (Serbian), kadu koppara (Sinhalese), lokjan (Marshallese), malasugi (Visayan), meda (Russian), mekajiki (Japanese), paea (Maori), pesce spada (Italian), pez espada (Spanish), sankeh (Arabic), swaardvis (Afrikaans), xiphias (Greek), and zwaardvisch (Dutch).

Importance to Humans

Swordfish fisheries are active in tropical and temperate waters worldwide. The nations with the highest swordfish catches in the North Atlantic are Spain, the USA, Canada, Portugal, and Japan. Brazil, Japan, Spain, Taiwan, and Uruguay are the nations that catch the most swordfish in the South Atlantic. In 1995, the Atlantic swordfish industry caught 36,645 tons, or 41 percent of the world total catch of swordfish.

Fisheries in the Atlantic primarily rely on longlines. In 1995, there were more than 1,900 active swordfish vessels in the US, most held by longlining vessels, although the fishery began as a harpooning industry. Canada has seen a significant increase in swordfish permits since their groundfish fisheries closed in the early 1990s.

Mediterranean swordfish are now believed to form a separate stock from the Atlantic stocks, however they are not totally isolated. In 1995, the Mediterranean catch accounted for 9 percent of the world total. In the Indian Ocean, swordfish concentrations occur off the coasts of India, Sri Lanka, Saudi Arabia, and eastern Africa. While the Indian fishery was traditionally largest in the eastern Indian Ocean, it has not been productive in recent years. The western Indian Ocean now dominates the regional catch, which amounted to 15 percent of the world total catch in 1995. Almost half the worldwide catch of swordfish occurs in the Pacific. The Pacific swordfish fishery is active in five areas: the northwestern Pacific, off southeastern Australia, off northern New Zealand, the southeastern tropical Pacific, and off Baja California, Mexico. As demand in North America and Europe increases and stricter quotas are set in the Atlantic, scientists expect Pacific swordfish will face more intense fishing pressure in coming years.

From 1948, when the world swordfish harvest was 7,000 tons, it grew steadily to 37,700 tons in 1970. That year, reports of high mercury levels in swordfish frightened many consumers, causing the demand to drop significantly. As fear of contamination subsided, the fishery resumed and now catches in excess of 80,000 tons per year.

The US imported 4,681 tons of swordfish in 1995 and caught 7,278 tons. That year, US processors handled 4,549 tons of swordfish meat, valued at $53.4 million. Of this, fillets constituted 2,920 tons and steaks accounted for 1,629 tons. In 1993, western Europe consumed 35,324 tons of swordfish, primarily in fillets or steaks. While consumption levels are not known for Asia, high-quality swordfish is valued as an ingredient in sashimi or sushi.

Conservation

Most of the swordfish taken by the U.S. fishing industry are juveniles. Recently, the US government took measures to protect juvenile north Atlantic swordfish stocks by closing swordfish nursery areas to fishing. Coupled with an international swordfish recovery plan (1999), swordfish populations are on the road to recovery.

> Check the status of the swordfish at the IUCN website.

The IUCN is a global union of states, governmental agencies, and non-governmental organizations in a partnership that assesses the conservation status of species.

Geographical Distribution

The swordfish is found in oceanic regions worldwide, including the Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian Oceans. It is found in tropical, temperate, and sometimes cold waters, with a latitudinal range of approximately 60°N to 45°S. The swordfish is a highly migratory species, generally moving to warmer waters in the winter and cooler waters in the summer. It is often present in frontal zones, areas where ocean currents collide and productivity is high.

Habitat

Generally an oceanic species, the swordfish is primarily a midwater fish at depths of 650-1970 feet (200-600 m) and water temperatures of 64 to 71°F (18-22°C). Although mainly a warm-water species, the swordfish has the widest temperature tolerance of any billfish, and can be found in waters from 41-80°F (5-27°C). The swordfish is commonly observed in surface waters, although it is believed to swim to depths of 2,100 feet (650 m) or greater, where the water temperature may be just above freezing. One adaptation which allows for swimming in such cold water is the presence of a “brain heater,” a large bundle of tissue associated with one of the eye muscles, which insulates and warms the brain. Blood is supplied to the tissue through a specialized vascular heat exchanger, similar to the counter current exchange found in some tunas. This helps prevent rapid cooling and damage to the brain as a result of extreme vertical movements.

Biology

Distinctive Features

The swordfish, as the only member of the family Xiphiidae, can be distinguished from other billfishes (Family Istiophoridae) by the shape of its prolonged “bill”, which appears as a flattened oval in cross section. The bill is long relative to other billfishes and adults lack teeth in the jaws. While the young have scales, these are lost by the time the fish attain a body length of about 3 feet (1 m). Adults lack scales and teeth. The body is generally cylindrical. Two dorsal fins are present, although the second is quite small, separated from the first, and set far back on the body. The first dorsal fin is high and rigid. Likewise, there are two anal fins, although again the second is considerably smaller than the first. Pelvic fins are absent. The caudal fin is lunate, while the caudal peduncle has a pronounced keel on either side. The lateral line is also present in specimens up to 3 feet (1 m) in body length, but it too is lacking in adulthood. Prior to adulthood, swordfish morphology changes greatly, as described below.

Coloration

The color is blackish-brown above, fading to a lighter shade below. The fins are brown or dark brown.

Size, Age, and Growth

Swordfish reach a maximum size of 177 in. (455 cm) total length and a maximum weight of 1,400 lbs. (650 kg), although the individuals commercially taken are usually 47 to 75 in. (120-190 cm) long in the Pacific. Females are larger than males of the same age, and nearly all specimens over 300 lbs. (140 kg) are female. Pacific swordfish grow to be the largest, while western Atlantic adults grow to 700 lbs. (320 kg) and Mediterranean adults are rarely over 500 lbs. (230 kg). The IGFA all tackle record is 1182 lb. (536.15 kg). Swordfish reach sexual maturity at 5-6 years of age, with a maximum lifespan of at least 9 years.

Food Habits

As opportunistic predators, swordfish feed at the surface as well as the bottom of their depth range (>2,100 ft (650 m)) as evidenced by stomach contents. They feed mostly upon pelagic fishes, and occasionally squids and other cephalopods. At lower depths they feed upon demersal fishes. The sword is apparently used in obtaining prey, as squid and cuttlefishes commonly exhibit slashes to the body when taken from swordfish stomachs. A recent study found the majority of large fish prey had been slashed, while small prey items had been consumed whole. Larval swordfish feed on zooplankton including other fish larvae. Juveniles eat squid, fishes, and pelagic crustaceans.

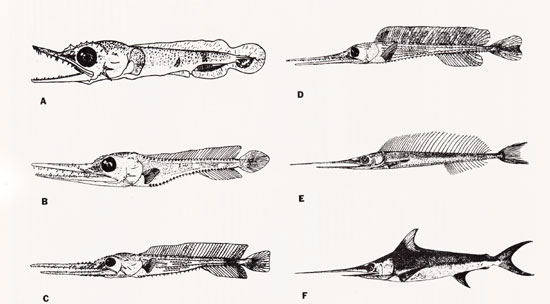

Reproduction

Swordfish have been observed spawning in the Atlantic Ocean, in water less than 250 ft. (75 m) deep. Estimates vary considerably, but females may carry from 1 million to 29 million eggs in their gonads. Solitary males and females appear to pair up during the spawning season. Spawning occurs year-round in the Caribbean Sea, Gulf of Mexico, the Florida coast and other warm equatorial waters, while it occurs in the spring and summer in cooler regions. The most recognized spawning site is in the Mediterranean, off the coast of Italy. The height of this well-known spawning season is in July and August, when males are often observed chasing females. The pelagic eggs are buoyant, measuring 1.6-1.8mm in diameter. Embryonic development occurs during the 2 ½ days following fertilization. As the only member of its family, the swordfish has unique-looking larvae. The pelagic larvae are 4 mm long at hatching and live near the surface. At this stage, body is only lightly pigmented. The snout is relatively short and the body has many distinct, prickly scales. With growth, the body narrows. By the time the larvae reach half an inch long (12 mm), the bill is notably elongate, but both the upper and lower portions are equal in length. The dorsal fin runs the length of the body. As growth continues, the upper portion of the bill grows proportionately faster than the lower bill, eventually producing the characteristic prolonged upper bill. Specimens up to approximately 9 inches (23 cm) in length have a dorsal fin that extends the entire length of the body. With further growth, the fin develops a single large lobe, followed by a short portion that still reaches to the caudal peduncle. By approximately 20 inches (52 cm), the second dorsal fin has developed, and at approximately 60 inches (150 cm), only the large lobe remains of the first dorsal fin.

Predators

Predators of adult swordfish include marine mammals such as killer whales. Young adults and juveniles are eaten by a variety of sharks and other large predatory fish including blue marlin (Makaira nigricans), black marlin (Makaira indica), sailfish (Istiophorus platypterus), yellowfin tuna (Thunnus albacares), and the dolphinfish (Coryphaena hippurus).Parasites

Swordfish are hosts to 49 species of parasites including cestodes (tapeworms) in the stomach and intestines, nematodes (roundworms) in the stomach, tremodes (flukes) on the gills, and copepods attached to the surface of the body. One such copepod is the Pennella filosa, a parasite that inserts itself into the flesh of the swordfish. Sea lampreys are also ectoparasites on swordfish. They leave behind longitudinal scratch marks indicating that swordfish are skilled at ridding themselves of the lamprey. Other parasites include digenea (flukes), didymozoidea (tissue flukes), monogenea (gillworms), cestoda (tapeworms), nematoda (roundworms), acanthocephala (spiny-headed worms), copepods, barnacles, and isopods. Ectoparasitic fish include the cookiecutter shark (Isistius brasiliensis), pilotfish (Naucrates ductor), sea lamprey (Petromyzon marinus), spearfish remora Remora brachyptera, and marlin sucker Remora osteochir.

Taxonomy

Linnaeus first described the swordfish in 1758, providing the name still in use today, Xiphias gladius. Translated to English, the Latin term gladius means “sword”, referring to the long sword-like bill. Other scientific names that have been used to refer to the swordfish include Xiphias imperator Bloch and Schneider 1801, Xiphias rondelettiLeach 1818, Phaethonichthys tuberculatus Nichols 1923, Xiphias estara Phillips, 1932, Tetrapterus imperator Rohl 1942, and Xiphias thermaicus Serbetis 1951.

Prepared by: Susie Gardieff