Seminole Field

University of Florida Vertebrate Fossil Locality PI004

Location

Along banks of Joes Creek (labeled Saint Joes Creek on Google Maps) and its tributaries; about 6 miles (10 km) northwest of downtown St. Petersburg and 3 miles (5 km) southeast of Seminole, Pinellas County, Florida; 27.81° N, 82.71° W.

Age

- Late Pleistocene Epoch; Rancholabrean land mammal age

- About 11,000 to 25,000 years old (estimated)

Basis of Age

Biochronology (presence of Sigmodon hispidus, Smilodon fatalis, Canis dirus, Tremarctos floridanus, Puma concolor, and Glyptotherium floridanum indicates a Rancholabrean age (Webb, 1974; Morgan and Seymour, 1997). A radiometric date of 2600 years before present done on charcoal from the area in the 1950s is undoubtedly too young and represents a more recent stream channel deposit that cut into the late Pleistocene bone bed (Bullen, 1964).

Geology

Fossils derive from a 1- to 2-foot-thick (30-65 cm) bed of fine brown sand that includes varying amounts of clay (Cooke, 1926). This layer rests on top of a white, shelly sand. Above the bone layer is several feet of unfossiliferous sand and organic material. This is a description of the original site from the 1920s. Bullen (1964) described in detail the geology about 0.5 miles to the west, which in some areas was similar to the original site and in others had been disturbed and re-work by streams during the Holocene.

Depositional Environment

Stream channels, oxbow lake, and flood deposits.

Fossils

Excavation History and Methods

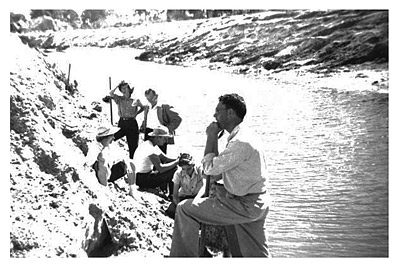

The locality was discovered by local resident Walter W. Holmes in 1924 (Figure 1). Holmes excavated the site with men he employed (Figure 2) and was joined periodically by staff of the American Museum of Natural History from 1925 to 1927 and in 1929 (Holmes and Simpson, 1931). Holmes donated almost all of his several thousand specimens to the American Museum of Natural History; about a dozen were instead given to the Florida Geological Survey. In the early 1950s a dredging operation straightened, widened, and deepened the creek into a drainage canal (Figure 3). This resulted in a second, less intensive round of collecting a short distance to the west of the original site by several individuals. E. McConkey donated 10 specimens collected in 1953 to the Florida Museum of Natural History, including a partial carapace of the giant box turtle Terrapene putnami (Auffenberg, 1958: figure 7A). Herbert Winters of the Florida Geological Survey led field parties that collected almost 400 specimens in 1953. The last known collecting effort was by the Pinellas County Science Center and Brian Ridgway in 1980, which produced about 150 specimens that were donated to the Florida Museum of Natural History. No known grid system was employed at any time. It is not known if matrix was screenwashed for microfossils, and if so, how much. Most specimens are from medium- or large-sized species.

Discussion

Seminole Field was one of the “Big Three” late Pleistocene sites discovered in Florida during the first half of the 20th Century. The other two were on the eastern (Atlantic) coast of the state, the Vero Canal Site in Indian River County and the Melbourne Site in Brevard County. In combination or separately they have been responsible for many dozens of scientific publications. Many of them were related the human bones and/or artifacts possibly found in the same deposits as those of Pleistocene vertebrates, at the time a very controversial idea and one not endorsed by the mainstream archaeological community. Prior to 1950, there was also controversy between paleontologists about whether the age of these sites was early or late Pleistocene. All three of these sites were found along Florida’s densely populated and highly developed coastline. Relatively few such sites have been found since the 1930s. It is likely that many more lie undiscovered hidden below shopping malls, parking lots, condos, and suburban homes and yards.

Seminole Field is a very significant locality from a purely paleontological perspective. Simpson (1929) described the mammals from the site, naming six new species, one new genus, and one new subspecies. Some of these are no longer considered valid, but three are widely recognized, not just in Florida: the glyptodont Glyptotherium floridanum, the armadillo Dasypus bellus, and the llama Palaeolama mirifica. The site’s large sample of teeth of the extinct tapir Tapirus veroensis formed the primary basis for a statistics-based analysis by Simpson (1945), one of the first such studies ever done on a fossil mammal. Among the larger herbivores, the most common at Seminole Field are, in order of decreasing abundance, deer, horse, tapir, bison, and long-nosed peccary (Mylohyus fossilis), which together make up most of the recovered mammals. Interestingly, of these five, two are generally considered primarily grazers living in open habitats, the bison and horse, while the other three are considered primarily browsers living in forested habitats. The site could represent a water hole or other area where animals from different habitats mingled, or this could be an artifact of postmortem transport. The excellent preservation of the bones, including several articulated glyptodont carapaces, argues against significant transport of the fossils following death.

Birds (Wetmore, 1931) and reptiles (Brattstrom, 1954; Auffenberg, 1963; Holman, 1995) are also very abundant at Seminole Field. The site was the first in Florida to produce the giant condor-like bird Teratornis, and one of the few to record the Whooping Crane, Grus americana. Species associated with wetlands and freshwater habitats are diverse, including ducks, swan, goose, rails, anhinga, grebes, herons, and the red-winged blackbird. Amphibians and reptile species in the faunal list that are not listed by Holman (1995) are based on specimens in the collections held by the Florida Museum of Natural History.

Sources

- Original Author(s): Richard C. Hulbert Jr.

- Original Completion Date: September 11, 2013

- Editor(s) Name(s): Richard C. Hulbert Jr., Natali Valdes

- Last Updated On: March 4, 2015

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant Number CSBR 1203222, Jonathan Bloch, Principal Investigator. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

Copyright © Florida Museum of Natural History, University of Florida