Tyner Farm

University of Florida Vertebrate Fossil Locality AL121

Location

About 3.5 miles (5.6 km) north of Newberry, western Alachua County, Florida; 29.70° N, 82.62° W.

Age

- Late Miocene Epoch; early Hemphillian (Hh1) land mammal age

- About 7.5 million years old (estimated)

Basis of Age

Vertebrate biochronology. Prior to the discovery of the Tyner Farm Site, late Miocene localities from north-central Florida (Alachua, Marion, and Levy counties) fell into two discrete age groups. The older of the two groups, termed the Archer Fauna by Webb and Hulbert (1986), includes the Love, McGehee Farm, Haile 19A, Mixson’s Bone Bed, and Emathla localities. They range in age from about 9.5 to 8.5 million years ago, Clarendonian 4 (Cl4) and Hh1. The younger group includes Withlacoochee River Site 4A, Moss Acres Racetrack Site, and Dunnellon Phosphate Mining Region sites. These are Hh2 in age, about 7 to 6 million years old. Tyner Farm shares the following species with Archer Fauna sites: Hemiauchenia minima, Aepycamelus major, Pediomeryx hamiltoni, Aphelops malacorhinus, Calippus hondurensis, and Amebelodon floridanus. Most of these species do not persist into the Hh2 interval. However, Tyner Farm shares Thinobadistes wetzeli with Florida Hh2 sites (as opposed to Thinobadistes segnis of the Archer Fauna). The species of the genus Nannippus present at Tyner Farm is more advanced than Nannippus westoni of the Archer Fauna. The sample of Aphelops malacorhinus at Tyner Farm is significantly larger than those at the Love Site and McGehee Farm, equaling in size the more derived species Aphelops mutilus found in Hh2 sites. Tyner Farm also resembles Hh2 sites, and differs from Hh1 sites in Florida in having Aphelops as the more common rhino.

The best current estimate for the age of Tyner Farm is in the second half of the Hh1 interval, probably close to its boundary with Hh2 (Hulbert and Whitmore, 2006).

Geology

At Tyner Farm, solution features in the Eocene limestone bedrock have been filled with phosphatic sandy clay mixed with limestone breccia. The clay is massive, lacking the laminations found at some other Florida sinkhole sites (e.g., Thomas Farm, Haile 7C). The limestone surface underlying the clay is extremely irregular, ranging from a depth of about 1 to 15 feet (0.3-4.5 m) below the surface. Overlying the clay is loose quartz sand, which also contains some late Miocene fossils, although they are not as abundant as in the clay. It is unclear whether the sand unit is Miocene or if it is a Pleistocene deposit containing reworked Miocene vertebrates. The latter is considered more likely.

There is some evidence that the clay and its fossils are not in their original depositional position, but have collapsed into void spaces created by dissolution of underlying limestone. This is considered likely due to the inclusion of limestone breccia deposits within the clay, the relative high angles of plunge found on many of the fossil bones (about a quarter of the bones are plunging at angles exceeding 45 degrees). Some large, sturdy bones of rhinos and gomphothere were found shattered in a manner suggesting breakage and crushing following fossilization. A similar scenario is thought to have occurred at the nearby McGehee Farm Site.

Depositional Environment

Although some aquatic forms are present (frogs, alligator, Pseudemys), they are relatively rare, suggesting a mostly dry, land site. The bones show no evidence of pre-burial weathering or waterwear, so they were relatively pristine when buried, except for some cases of carnivore bite marks. The surrounding habitat was predominantly covered with trees and brush, with relatively little open grassland, based on the make-up of the mammalian fauna.

Fossils

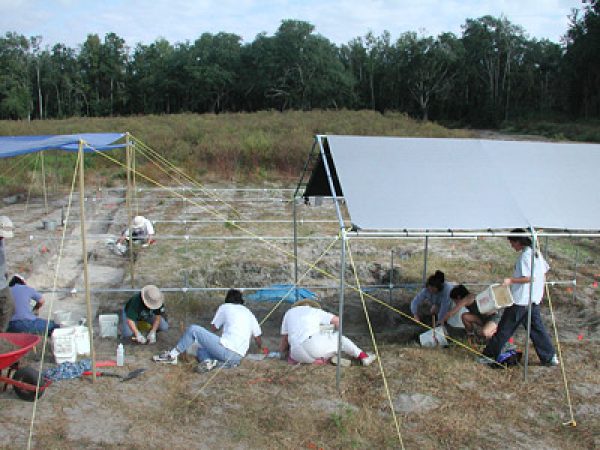

Figure 1. Museum field crew excavates the upper, sandy layer at Tyner Farm in October 2001.

Figure 1. Museum field crew excavates the upper, sandy layer at Tyner Farm in October 2001. Figure 1. Museum field crew excavates the upper, sandy layer at Tyner Farm in October 2001.

Figure 1. Museum field crew excavates the upper, sandy layer at Tyner Farm in October 2001. Figure 3. A green-colored clay found draped around limestone and filled solution depressions produced the most fossils at Tyner Farm. Here museum volunteer Don Munroe excavates a rhino humerus in November 2001.

Figure 3. A green-colored clay found draped around limestone and filled solution depressions produced the most fossils at Tyner Farm. Here museum volunteer Don Munroe excavates a rhino humerus in November 2001.

Excavation History and Methods

The Tyner Farm site was discovered in the spring of 2001 by Bruce and Allan Tyner of Newberry while plowing a field to plant peanuts. After the discovery of fragmented fossil bones, the Tyners contacted the Florida Museum of Natural History. Realizing the potential importance of the site, the Tyners allowed the Florida Museum of Natural History to excavate in this field with all obtained fossils going to the museum upon collection. Work at the site lasted until June 2005, with over 300 museum employees and volunteers excavating the site mainly during the fall and spring months.

The locality was gridded into squares 1 x 1 meter. Detailed location, depth, and orientation data were recorded for all fossils greater than 1 cm in size (Figures 4-5). Approximately 5,000 kg (over 5 tons) of sediment from the site was transported to the paleo lab at the Florida Museum of Natural History and washed through a series of nested screens. Although not especially rich in microfauna compared to some other Florida sites, fossils of small mammals, reptiles, and amphibians were recovered by this method. In total, over 3,000 identifiable fossil specimens representing at least 40 different species were collected during the four-year-excavation at Tyner Farm. Excavations ceased in the spring of 2005 when the limestone floor was reached at depths of 2 to 15 feet in all areas of the site. It was subsequently back-filled and is no longer accessible.

Figure 4. Museum staff member Richard Hulbert determines the relative depth and location of a rhino femur within the grid system at Tyner Farm. Image taken on November 13, 2003.

Figure 4. Museum staff member Richard Hulbert determines the relative depth and location of a rhino femur within the grid system at Tyner Farm. Image taken on November 13, 2003. Figure 5. Museum staff member Richard Hulbert uses a Brunton compass the determine the bearing (measured in degrees east of north) of a rhino femur. Image taken on November 13, 2003.

Figure 5. Museum staff member Richard Hulbert uses a Brunton compass the determine the bearing (measured in degrees east of north) of a rhino femur. Image taken on November 13, 2003.

Discussion

Though the Tyner Farm site produced a large number of significant fossils during the four years of excavation, they remain largely unstudied. The populations belonging to the genera Thinobadistes, Aphelops, and Nannippus at Tyner Farm are especially important, as they appear to be samples of lineages taken during times of rapid evolution. Careful study of each will be needed to properly determine their taxonomy. Tyner Farm is also important because it provided many more microvertebrate fossils than are usually found in similar sites of this age, providing a fuller glimpse of the ancient ecology of Florida during the late Miocene. The most abundant component of the microvertebrate fauna are colubrid snakes, with toads and lizards also common. Small mammals include a vespertilionid bat, an extinct small mouse (Abelmoschomys), and the tree squirrel Sciurus. The latter is the oldest records of tree squirrels in eastern North America.

Figure 6. Museum volunteer Heather Pugh uncovers a mandible of Nannippus on November 6, 2003 in the green clay zone at Tyner Farm.

Figure 6. Museum volunteer Heather Pugh uncovers a mandible of Nannippus on November 6, 2003 in the green clay zone at Tyner Farm. Figure 7. Museum staff member Art Poyer working at Tyner Farm in November 2003 along with volunteers Mary Lynch (left) and Barbara Toomey (right). In much of the site all of the clay has been removed, revealing the irregular topography of the limestone surface.

Figure 7. Museum staff member Art Poyer working at Tyner Farm in November 2003 along with volunteers Mary Lynch (left) and Barbara Toomey (right). In much of the site all of the clay has been removed, revealing the irregular topography of the limestone surface.

Sources

- Original Author(s): Sean M. Moran and Richard C. Hulbert Jr.

- Original Completion Date: October 9, 2013

- Editor(s) Name(s): Richard C. Hulbert Jr., Natali Valdes

- Last Updated On: March 4, 2015

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant Number CSBR 1203222, Jonathan Bloch, Principal Investigator. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

Copyright © Florida Museum of Natural History, University of Florida