Ciconia maltha

Quick Facts

Common Names: Asphalt stork or La Brea stork

A relatively large species of Ciconia, with a height of over 4 feet (1.5 m) and a wingspan up to 9 feet (3 m) across.

While many large mammals became extinct at the end of the Pleistocene in North America, Ciconia maltha is one of the few large birds to suffer the same fate.

Today, six species of storks in the genus Ciconia live in the Old World and one species lives in South America.

Age Range

- Late Pliocene and early to late Pleistocene Epochs; Blancan to Rancholabrean land mammal ages

- About 3.5 million to 12 thousand years ago

Scientific Name and Classification

Ciconia maltha Miller, 1910

Source of Species Name: Because the type specimen was from the Rancho La Brea tar pits, the species name was taken from the Latin word maltha, meaning asphalt or wax.

Classification: Aves, Neornithes, Neognathae, Neoaves, Ciconiiformes, Ciconiidae

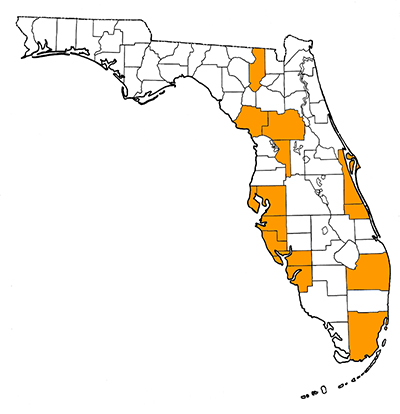

Overall Geographic Range

The species ranges across the continental United States, including but not limited to Oregon, Idaho, California, and Florida; and is also known from Cuba and Bolivia (Agnolin, 2006). The type locality is Rancho La Brea, Los Angeles County, California (Miller, 1910; Howard, 1942).

Florida Fossil Occurrences

Florida fossil sites with Ciconia maltha:

Discussion

Ciconia maltha is an extinct species belonging to the family Ciconiidae, which is represented by extinct and extant species of birds with long bills, necks, and legs, and medium to large-sized bodies. Members of the family Ciconiidae are commonly known as storks. Currently, the only storks living in North America are Mycteria americana, the wood stork, which is also found in Cuba and Hispaniola (Raffaele et al., 1998), and Jabiru mycteria, which ranges from Mexico through Central America to Argentina. The fossil record for storks shows greater species diversity in North America during the Pleistocene and earlier (Howard, 1942; Brodkorb, 1963; Short, 1966; Becker, 1987; Bickart, 1990; Emslie, 1998; Olson and Rasmussen, 2001). The only fossil evidence for storks in Cuba was based on two specimens recovered in Cienfuegos, Cuba (Suarez and Olson, 2003), which were originally identified as Jabiru mycteria (Wetmore, 1928). Howard (1942) later re-examined these specimens and reassigned them to the species Ciconia maltha.

That said, the number of fossil storks species from North America has been historically unclear (Feduccia, 1967). This may primarily be because of the variation described in species of extinct storks. In Howard’s (1942) study, all known specimens of storks of the time were compared and it was concluded that they represented a highly variable Ciconia maltha (see Feduccia, 1967). Feduccia (1967) compared fossil material between Ciconia maltha and Jabiru mycteria to test Howard’s (1942) assessment and found that there was variation in size and osteological characters within both species (also noted by Wetmore, 1931). However, Feduccia agreed with Howard and Miller that the fossils are more properly assigned to Ciconia rather than Jabiru, contrary to Wetmore (1931).

The first report of a large stork from the fossil record of Florida was by Sellards (1916). He described bones from the wing (humerus, ulna, carpometacarpus, and coracoid) from the Vero Canal Site. Sellards named the species Jabiru? weillsi on the basis of these specimens. Sellards was unsure about the generic allocation of his new species (hence the use of a question mark) and did note one feature of the coracoid that was more similar to Ciconia than Jabiru. He made no comparisons with Ciconia maltha named by Loye Miller six years earlier and based on specimens from Rancho la Brea. But Miller (1910) had primarily based his new species on bones from the hind limb and a partial beak, so at the time there was only the coracoid upon which to make a direct comparison between the two species. It is possible that Sellards was simply unaware of Miller’s new stork. Wetmore (1931) was the next person to study fossil storks from Florida. He noted three additional records (Ichetucknee River, Melbourne, and Seminole Field). Wetmore regarded these and the Vero specimens previously worked on by Sellards as belonging to the extant species Jabiru mycteria. Howard (1942) was the first to regard the Florida specimens as conspecific with the fossils of Ciconia maltha from California.

Fossils of Ciconia maltha are frequently recovered from Florida sites that also produce a large number of “waterfowl” and other birds that today live near freshwater habitats, such as herons, grebes, and rails. Storks today live in a variety of habitats that may or may not include open bodies of water, and feed on large insects such as grasshoppers and beetles as well as snails and many types of smaller vertebrates (Tsachalidis and Goutner, 2002). Many species of storks are migratory and fly long distances between breeding and wintering locations. It is not clear how closely Ciconia maltha resembled modern members of the genus Ciconia in its ecology and life history, but given their morphologic similarity, it seems likely that the asphalt stork lived in a similar manner to extant species of Ciconia and to Jabiru mycteria.

Those wishing to view images of the holotype humerus of Jabiru? weillsi from the Vero Canal Site can do so at the on-line database of the Department of Paleobiology of the National Museum of Natural History. The URL is http://collections.nmnh.si.edu/search/paleo/. Click on the Search by Field button and enter “V 9712” in the catalog number box. Then click on the search button. There will be one result. Click on the + symbol to open a window, and then click on the thumbnail image to view a larger version. This specimen was formerly in the Florida Geological Survey collection, but was transferred to the Smithsonian after the survey’s director Sellards left for Texas.

Sources

- Original Authors: Richard C. Hulbert Jr. and Natali Valdes

- Original Completion Date: February 16, 2013

- Editors: Natali Valdes and Richard C. Hulbert Jr.

- Last Updated On: May 21, 2015

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant Number CSBR 1203222, Jonathan Bloch, Principal Investigator. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

Copyright © Florida Museum of Natural History, University of Florida