Floridaophis auffenbergi

Quick Facts

Common Name: none

Known from only a single specimen, an isolated vertebra.

One of the oldest known colubrids (nonvenomous constricting snakes) in North America.

A species of very small size; the anatomy of the vertebrae suggest a terrestrial rather than aquatic ecology.

Age Range

- Early Oligocene Epoch; Whitneyan land mammal age

- About 32 to 30 million years ago

Scientific Name and Classification

Floridaophis auffenbergi Holman, 1999

Source of Species Name: The genus name makes reference to Florida, the state where the fossils were found, and ophi– comes from the Greek meaning “snake”. The species name was chosen in recognition of Dr. Walter Auffenberg who was an important pioneer in the study of fossil snakes in the southeastern part of the United States.

Classification: Reptilia, Diapsida, Lepidosauromorpha, Lepidosauria, Squamata, Serpentes, Alethinophidia, Macrostomata, Colubroidea, Colubridae

Alternate Scientific Names: none

Overall Geographic Range

This species is only known from early Oligocene sediments of Central Florida (I-75 site).

Florida Fossil Occurrences

Florida fossil sites with Floridaophis auffenbergi:

- Alachua County—I-75 site

Discussion

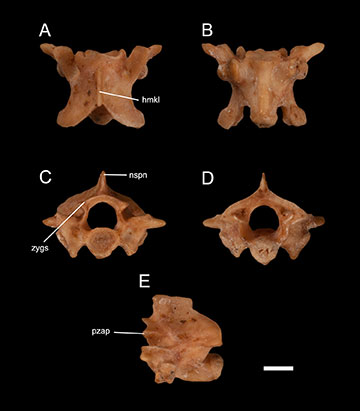

Floridaophis auffenbergi is a very small species of colubrid snake that is characterized by having trunk vertebrae that are wider than long, a vaulted neural arch, neural spines that are thin and well developed, and the absence of epizygapophyseal spines (Figure 2). Another colubrid snake, Nebraskophis oligocenicus, is also present in the I-75 Local Fauna (Holman, 1999). F. auffenbergi differs from N. oligocenicus by being smaller, having a less vaulted neural arch, and a more developed neural spine (Figure 2C; Holman, 1999). It has been suggested that the high neural spine of F. auffenbergi indicates that it was a terrestrial taxon (Holman, 1999).

Nebraskophis sp. is the oldest known colubrid snake from North America from the late Eocene (Chadronian) of central Georgia, U.S. (Parmley and Holman, 2003), followed by the early Oligocene (Orellan) Texasophis galbreathi (Holman, 1984) from eastern Colorado, and the Whitneyan fossil colubrids from the I-75 Local Fauna in Florida (Holman, 1999; Parmley and Holman, 2003). The record of Floridaophis auffenbergi and Nebraskophis oligocenicus (Holman, 1999) in the I-75 site represents the earliest record of colubrid snakes in the state of Florida and also provides new information on the evolution and origin of early archaic colubrids in general. Presence of these taxa in eastern U.S. confirms a dry-land connection between the ancient Florida peninsula and western North American continental territories, at least during the late Eocene-early Oligocene (Holman, 1999).

Based on the Paleogene distribution of the family Colubridae in Asia, Europe, and North America, two competing hypotheses have been proposed to explain the biogeographic evolution of the North American colubrids: 1) the migration of archaic colubrids from Eurasia could have occurred during the early Paleogene, suggesting that the North American forms have a Euroasiatic ancestor (Holman, 1999); or 2) Nebraskophis may have had an autochthonous North American origin. In this case, endemic North American colubrids appeared during the Eocene in southeastern North America and reached the Great Plains by the middle Miocene (Holman, 2000). Unfortunately, the phylogenetic relationship among the archaic colubrids from North America, Europe, and Asia is poorly understood (Parmley and Holman, 2003) and cannot yet shed light on either hypothesis.

Sources

- Original Author(s): Aldo F. Rincon

- Original Completion Date: December 7, 2012

- Editor(s) Name(s): Natali Valdes

- Last Updated On: March 3, 2015

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant Number CSBR 1203222, Jonathan Bloch, Principal Investigator. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

Copyright © Florida Museum of Natural History, University of Florida