Haliaeetus leucocephalus

Quick Facts

Common Name: bald eagle

Fossils of this species are very rare.

Only known from the late Pleistocene. Eagles are known from the early Pleistocene of Florida, but they are extinct species not closely related to the bald eagle.

Age Range

- Late Pleistocene Epoch; Rancholabrean land mammal age

- About 125,000 years ago to present

Scientific Name and Classification

Haliaeetus leucocephalus Linnaeus, 1766

Source of Species Name: The species name is derived from the Greek leuco, meaning ‘white’, and cephalis, meaning ‘head’. This name is in reference to the white plumage on its head (Dudley, 1998).

Classification: Reptilia, Aves, Neognathae, Neoaves, Accipitriformes, Accipitridae

Alternate Scientific Names: Haliaetus leucocephalus; Falco leucocephalus

Overall Geographic Range

In addition to Florida, fossils of Haliaeetus leucocephalus have been found scattered across the United States, including sites in California, Alabama, and Virginia (Guthrie, 1992; Parmalee, 1992). The species is extant, and modern Haliaeetus leucocephalus has a distribution covering all of North America (Dudley, 1998).

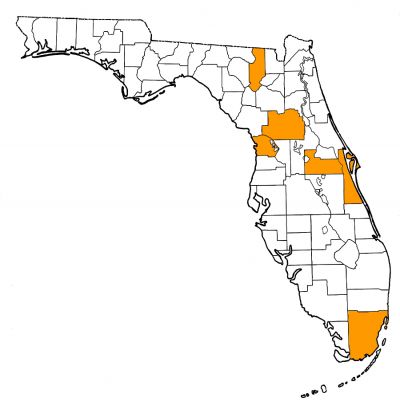

Florida Fossil Occurrences

Florida fossil sites with Haliaeetus leucocephalus:

- Brevard County-Melbourne

- Citrus County—Sabertooth Cave

- Columbia County—Ichetucknee River; Santa Fe River 2

- Dade County—Cutler Hammock

- Marion County—Reddick 1C; Silver Glen Spring

- Orange County—Rock Springs

Discussion

Despite its modern distribution across North America, the fossil record for the Bald Eagle is sparse. Haliaeetus leucocephalus first appears in the fossil record of Florida during the late Pleistocene, approximately 125,000 years ago, and it is around this time that it first appears elsewhere in the country (Guthrie, 1992; Parmalee, 1992; Emslie, 1998). Although the late Pleistocene avifauna has been particularly well studied for Florida and is represented by many dozens of sites (Emslie, 1998), less than 17 fossils of Haliaeetus leucocephalus have been recovered from eight sites, spanning only six counties.

The genus Haliaeetus, or ‘Sea Eagles’, is a member of the family Accipitridae. Accipitridae consists of diurnal predatory birds, which includes other eagles, kites, hawks, harries, and Old World vultures (Wink et al., 1996). Although there has been some dispute

as to the degree to which convergent evolution contributes to the similarities between members of this group (due to their similar ecology and feeding habits), molecular studies on the phylogeny of both the genus Haliaeetus and the family Accipitridae support the monophyly of these groups generally (e.g. Wink et al., 1996).

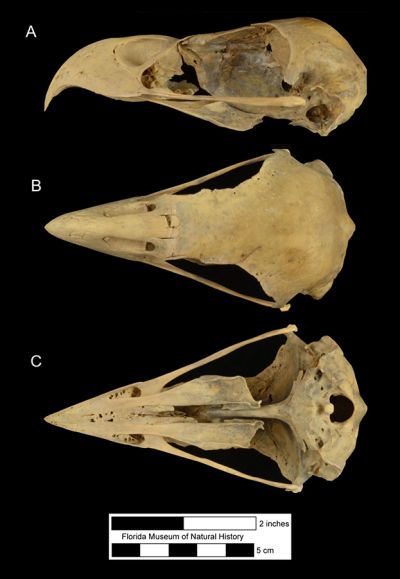

Modern individuals of Haliaeetus leucocephalus are piscivorous raptors, though they tend to feed on a variety of small land animals as well (Hertel, 1995; Dudley, 1998). Like many other accipitrids, Haliaeetus leucocephalus uses its sharp talons (Figure 2) to capture and kill its prey, and its large, curved beak (Figure 3) is used primarily for tearing apart prey once it has been caught (Hertel, 1995). Studies on the skull and beak shape of Haliaeetus leucocephalus fossils, particularly those collected from the Rancho La Brea Tar Pits in California (late Pleistocene), suggest a similar prey preference and feeding style among fossil and modern individuals (Hertel, 1995). Additional information on modern Haliaeetus leucocephalus can be accessed through the Animal Diversity Web.

Although Haliaeetus leucocephalus is relatively rare in the Florida fossil record, it has proven useful for reconstructing the paleoenvironment during the late Pleistocene. Cutler Hammock, an important Rancholabrean site in Dade County, Florida, includes fossils of Haliaeetus leucocephalus as well as other raptorial birds and abundant fossil material from small vertebrates, such as amphibians and reptiles (Emslie and Morgan, 1995).

Consequently, this site has been interpreted to represent a nesting and feeding site for predatory birds, including H. leucocephalus. Interestingly, the fauna collected from this site also suggests its use as a den for dire wolves and other carnivores, and later by humans during the early Holocene (Emslie and Morgan, 1995). Emslie (1998) further expanded upon the reconstruction of the Cutler Hammock site by incorporating the ecology of extant birds whose fossil remains have been recovered there. Based on the presence of Haliaeetus leucocephalus at this site, as well as its modern distribution among “freshwater aquatic and semi-aquatic” and “coastal and marine” habitats, the Cutler Hammock site was interpreted to be near the Late Pleistocene coast of Florida, and likely represents a lowland marsh and wetland environment with surrounding trees (Emslie and Morgan, 1995; Emslie, 1998).

Sources

- Original Author: Sarah Widlansky

- Original Completion Date: December 14, 2012

- Editors’ Name: Natali Valdes; Richard Hulbert Jr.

- Last Updated On: September 16, 2015

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant Number CSBR 1203222, Jonathan Bloch, Principal Investigator. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

Copyright © Florida Museum of Natural History, University of Florida