Kyptoceras amatorum

Quick Facts

Common Name: none

The youngest member of its family, which became extinct at the end of the Hemphillian.

The Florida Museum of Natural History has 44 specimens of the species in its collection.

The species name honors the many contributions of amateur fossil collectors to Florida paleontology.

Age Range

- Very early Pliocene Epoch; Hemphillian 4 land mammal age

- About 5 to 4.6 million years ago

Scientific Name and Classification

Kyptoceras amoratum Webb, 1981

Source of Species Name: The species name amatorum (“of the amateurs,” from the Latin amator, lover) was given in recognition of the contributions to paleontology made by amateur fossil collectors like Frank A. Garcia, who discovered and donated the type specimen to the Florida State Museum (now the Florida Museum of Natural History).

Classification: Mammalia, Eutheria, Laurasiatheria, Artiodactyla, Ruminantiamorpha, Ruminantia, Tragulina, Protoceratidae, Synthetoceratinae, Kyptoceratini

Alternate Scientific Name: none

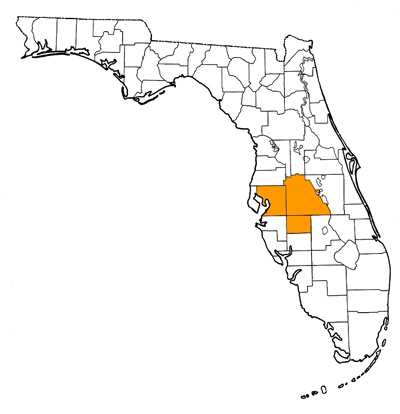

Overall Geographic Range

Southeastern United States, central Florida and eastern North Carolina (Eshelman and Whitmore, 2008). Type locality is Tiger Bay Mine, Central Florida Phosphate District, Polk County, Florida (Webb, 1981).

Florida Fossil Occurrences

Florida fossil sites with Kyptoceras amatorum:

- Hardee County—Fort Green Mine

- Hillsborough County—Four Corners Mine

- Polk County—Palmetto Fauna (Fort Green Mine; Fort Meade Mine (Gardenier); Hookers Prairie Mine; Nichols Mine; Noralyn Mine; Palmetto Mine; Phosphoria Mine; Rockland Mine; Silver City Mine; Tiger Bay Mine)

Discussion

The family Protoceratidae is an extinct group of generally rare, sexually dimorphic artiodactyls, best known for their unique hornlike structures adorning the skulls in adult male individuals (although some early members of the family lack horns). Kyptoceras amatorum is a member of the subfamily Synthetoceratinae, which bore a pair of horns (more accurately called ossicones, but for simplicity they are hereafter referred to as horns) over the orbits and a split “Y”-shaped horn on the rostrum (Fig. 2). They had relatively short legs with four functioning digits on the foreleg, and two on the hind legs. Until recently, the most widely accepted classification placed Protoceratidae within the Tylopoda, and thus most closely related to camels among living artiodactyls (Patton and Taylor, 1971; Prothero, 1998; Webb et al., 2006). However, an analysis of the evolutionary relationships among artiodactyls and cetaceans by Spaulding et al. (2009) found that they were instead more closely related to ruminants, a result in accord with the detailed study of Norris (2000) of the ear region in an Eocene protoceratid. This newer classification is followed above, but should be regarded as tentative.

Kyptoceras amatorum is the geologically youngest and most advanced protoceratid. It shares several derived features with another advanced species, Synthetoceras tricornatus, in that it is large in size, and has a more hypsodont dentition, occipital bones with elaborate condular “saddles,” horns with subcircular cross sections, and a dorsal orifice behind the rostral horn that is nearly (or in the case of Kyptoceras amatorum, fully) closed. Yet despite these shared features, Kyptoceras amatorum appears to be more closely related to Syndyoceras cooki, the most basal member of the subfamily. This interpretation is largely based on the structure of the horns, which are nearly reverse in nature to Synthetoceras tricornatus. Webb (1981) distinguished the two opposing developmental pathways by splitting them into the tribes Synthetoceratini and Kyptoceratini. The Florida Museum of Natural History has 44 specimens from Florida of the species in its collection. All derive from the phosphate mines of central Florida (Webb et al., 2008).

Many of the features that distinguish Kyptoceras amatorum from other synthetoceratines are defined by the horns (Figs. 2-3). The rostral horn lacks any supporting shaft and bifurcates near its base, as in Syndyoceras cooki, but is anteriorly angled about 60 degrees above the horizontal (the horns of other synthetoceratines, including the rostral horn of Syndyoceras cooki, are posteriorly angled). The cross section of each rostral horn is circular, rather than transversely ovate, and lacks rugosities. The horns taper to anteroventrally beveled points, rather than terminating with the knobbed feature found in other synthetocerines.

These same features are also found in the frontal horns, but with the added characteristic that their arc length is the greatest of any protoceratid (about 21 inches or 530 mm), being nearly twice the length of those found in the similarly-sized Synthetoceras tricornatus. While the frontal horns of other Synthetoceratidae curve laterally and then medially or posteriorly over the orbits (Patton and Taylor, 1971), those of Kyptoceras amatorum curve laterally and posteriorly to the orbits, then widely arc laterally and anterodorsally (Fig. 2). The last third of the horn is angled 60 degrees above the horizontal, paralleling the rostral horn (Webb, 1981).

The ‘horns’ of Kyptoceras amatorum (as in all Synthetoceratidae) are actually the expanded portions of the maxillary and frontal bones of the skull into hornlike protuberances called ossicones. Unlike true horns, which are covered with keratinous sheaths, the ossicones of Kyptoceras amatorum and other members of this family were covered with thickened skin. These structures are strongly textured with vascular grooves running along their lengths, which served as tracks for blood vessels (Fig. 4). Modern giraffes and okapi also have similarly structures.

The formation of the maxillary or rostral horn in Kyptoceras amatorum and other synthetocerines is tied to the formation of the nasal bones. The nasals of most protoceratids are highly reduced (Prothero and Ludtke, 2007), which creates a narrow, elongate dorsal opening in the narial region of the skull. The maxillary bones rise above this gap and fuse together before bifurcating laterally, resulting in a forked rostral horn about 8 inches (200 mm) long from the base to the tip of each horn, with about a 6 inch (150 mm) gap between tips. This process of bridging and fusing across the narial passage creates a narial orifice just behind the horn in all Synthetocerines except for Kyptoceras amatorum. This is because the maxillae completely fuse together behind the horn in this species (Webb, 1981).

The variations to the horns of both Kyptoceratini and Synthetoceratini are such that either the rostral horn or the frontal horns became larger and more pronounced than the other. Within Kyptoceratini, the frontal horns became the longer, more exaggerated feature, while the rostral horn became shorter and less emphasized; the reverse condition is found in the Synthetoceratini. The horns of Kyptoceras amatorum, like other synthetoceratines, are arranged so that they are best displayed from the front (in contrast to its sister subfamily, the Protoceratinae, whose horns are compressed laterally so that they were best viewed from the side).

As well as used for species recognition and rival intimidation, the male Kyptoceras amatorum may have used its horns for grappling in contests of strength. Webb (1981) proposed that the angle of the rostral horn, when interlocked with another, would safely catch the horn of its opponent and deflect the head downward, until the frontal horns also locked into position; due to the angle of the horns, no harm would have come to the combatants’ heads. With the stronger neck muscles and condular saddles of the skull, which act as stops to prevent overflexion between the skull and atlas, the fight would become a pushing contest, rather than one of physical injury.

The teeth of Kyptoceras amatorum are the most hypsodont (tallest crowned) of any protoceratid (Webb, 1981, Prothero and Ludtke, 2007). The upper molars are characterized by the absence of a lingual cingulum (present in other protoceratids), the possession of a large accessory cusp between narrow lingual selenes, and five well-developed labial ribs and styles with enamel walls covered by a layer of cement. The lower molars also lack a cingulum as well as accessory cusps, but are otherwise similar to lower molars of Synthetoceras tricornatus (except for its taller crown height) in that the labial wall is flat and lacks any stylids (Fig. 6).

As there are no clear modern analogues to members of the Protoceratidae, the paleoecology of this group is difficult to determine. Based on the short legs, unfused metapodials, and retention of four digits on the forelegs (inferred traits from other Synthetocerines, as the material of Kyptoceras amatorum consists largely of teeth and horn core fragments), they may have been adapted for living in marshes or dense forest rather than open plains. Stable isotope analysis of tooth enamel from an upper molar of Kyptoceras amatorum also indicated that they were probably deep forest browsers (Webb et al., 2003). Limb proportions, as well as alterations to the patella, metatarsals, and calcaneum may have acted to stiffen the hind legs so that the Synthetoceratines could rear up on two legs to feed in higher browse, as well as to afford leaping and bounding, much like the modern bushbuck (Tragelaphus scriptus) (Webb et al., 2003). It has been suggested that the retracted nasals and the large depression for the nasolabialis muscle of the Protoceratidae indicate the presence of a prehensile lip, snout, or short proboscis as a feeding apparatus like those found in moose or tapirs (Alces and Tapirus, respectively) (Patton and Taylor, 1973, Prothero, 1998, Webb et al., 2003).

The evolutionary progression (particularly in the horn development) of the Synthetoceratini is well represented in the North American fossil record, primarily from the central United States. This is not so for the Kyptoceratini, where only the first and last members of the tribe have been named, with many millions of years separating the two species. It has been suggested that Kyptoceras amatorum and its ancestors may have inhabited the subtropical savannas of Central America, where relevant fossil records are not well represented. The presence of a possible new genus and species of kyptoceratine from the early Miocene of southern Mexico reported by Montellano-Ballesteros and Jiménez-Hildalgo (2006) supports this hypothesis. After the extinction of Synthetoceras in the late Miocene, kyptoceratines may have then expanded their range to include the Gulf and Atlantic Coastal Plains (Webb et al., 2003; Eshelman and Whitmore, 2008).

Sources

- Original Author(s): Danielle R. Byerley

- Original Completion Date: December 7, 2012

- Editor(s) Name(s): Richard C. Hulbert Jr. and Natali Valdes

- Last Updated On: February 27, 2015

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant Number CSBR 1203222, Jonathan Bloch, Principal Investigator. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

Copyright © Florida Museum of Natural History, University of Florida