Pandion lovensis

Quick Facts

Common Name: Love Site osprey

Although ospreys are commonly seen today around bodies of fresh water, their fossils are very rare. This extinct species is only known from a total of eight specimens.

Its talons and hind limbs are not as well adapted for catching and holding onto fish as those in the living osprey.

Age Range

- Late Miocene Epoch; latest Clarendonian land mammal age

- About 9 million years ago

Scientific Name and Classification

Pandion lovensis Becker, 1985

Source of Species Name: Named after its type locality, the Love Bone Bed, which took its name from the property owners.

Classification: Aves, Neornithes, Neognathae, Neoaves, Accipitriformes, Pandionidae

Alternate Scientific Names: None

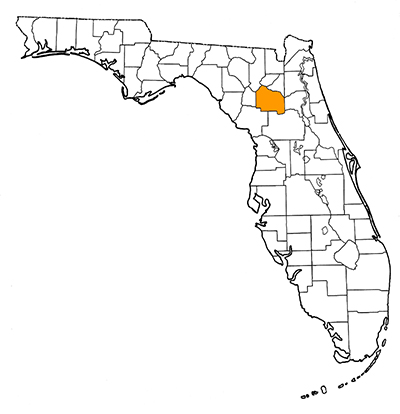

Overall Geographic Range

Only known from the type locality, Love Bone Bed (=Love Site) in southwestern Alachua County, Florida.

Florida Fossil Occurrences

Florida fossil sites with Pandion lovensis:

- Alachua County—Love Bone Bed

Discussion

Extinct ospreys belonging to the genusPandion have been recovered from several places around the world, including the middle Miocene of California (Pandion homalopteron; Warter, 1976), the late Miocene of Florida (Pandion lovensis; Becker, 1985), and the Oligocene of Egypt (Rasmussen et al., 1987). The sole living member of the genus Pandion is the species Pandion haliaetus. Pandion haliaetus has a worldwide distribution across all continents except Antarctica. Extant osprey fossils from Florida are known from the late Pleistocene (Hulbert and Becker, 2001).

Pandion lovensis is the most primitive member of the genus based on the morphology of its hindlimb (Becker, 1985), and it is also the most hawklike of the family Pandionidae. Its hindlimb is considered less adapted for grasping fish when compared to the modern form (Hulbert and Becker, 2001). See Figure 2 for a comparison of the talon morphology of Pandion lovensis and Pandion haliaetus. One of the features that distinguishes Pandion lovensis from the extant species is its longer and more slender tasometatarsus (Figure 3) and a wider and shallower intercondylar sulcus in its tibiotarsus (Figure 4).

Sources

- Original Author: Zachary Seth Randall

- Original Completion Date: November 30, 2012

- Editor(s) Name: Natali Valdes

- Last Updated On: May 7, 2015

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant Number CSBR 1203222, Jonathan Bloch, Principal Investigator. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

Copyright © Florida Museum of Natural History, University of Florida