Tapirus webbi

Quick Facts

Common Name: Webb’s tapir

The oldest known species of Tapirus from Florida. Starting with this species, tapirs were a common component of Florida’s fauna for about 9 million years, until their extinction about 12,000 years ago.

Some features of the skull suggest that Tapirus webbi could be a close relative (“ancestor”) of the modern Brazilian and mountain tapirs of South America.

Age Range

- Late Miocene Epoch; very late Clarendonian to early Hemphillian land mammal ages

- About 9.5 to 8 million years ago

Scientific Name and Classification

Tapirus webbi Hulbert, 2005

Source of Species Name: Named after former Florida Museum of Natural History Curator of Vertebrate Paleontology Dr. S. David Webb. He was prominently involved in directing field operations at both the McGehee Farm site, the type locality for the species, and the Love Bone Bed, which produced the largest known sample of the species.

Classification: Mammalia, Eutheria, Laurasiatheria, Perissodactyla, Tapiromorpha, Tapiroidea, Tapiridae

Alternate Scientific Names: Tapirus simpsoni

Overall Geographic Range

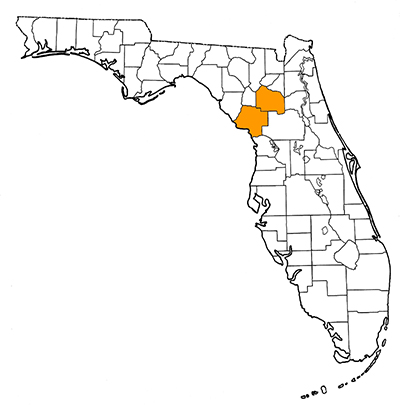

Known only from north-central Florida.

Florida Fossil Occurrences

Florida fossil sites with Tapirus webbi:

- Alachua County—Love Bone Bed; McGehee Farm

- Levy County—Mixson’s Bone Bed

Discussion

Up until 2005, Florida paleontologists followed the work of Yarnell (1980) who had determined that the large, late Miocene tapir in Florida was Tapirus simpsoni, a species originally named from Nebraska. Hulbert (2005) presented evidence that the Florida Miocene tapir was distinct from Tapirus simpsoni, and named it as a new species, Tapirus webbi. The best sample is from the Love Bone Bed, which preserves a minimum of 24 individuals, the second largest assemblage of fossil tapirs in Florida. This number is exceeded only by the approximately 70 individuals of Tapirus lundeliusi recovered at Haile 7G.

Tapirus webbi is a large species of tapir, with an estimated average mass of 400 kg (880 pounds), about equal to the largest living species, Tapirus indicus. Compared to other species of Tapirus, the limb bones of Webb’s tapir are longer, an indication that it lived in more open habitats than other species.

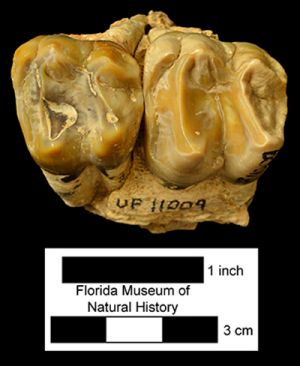

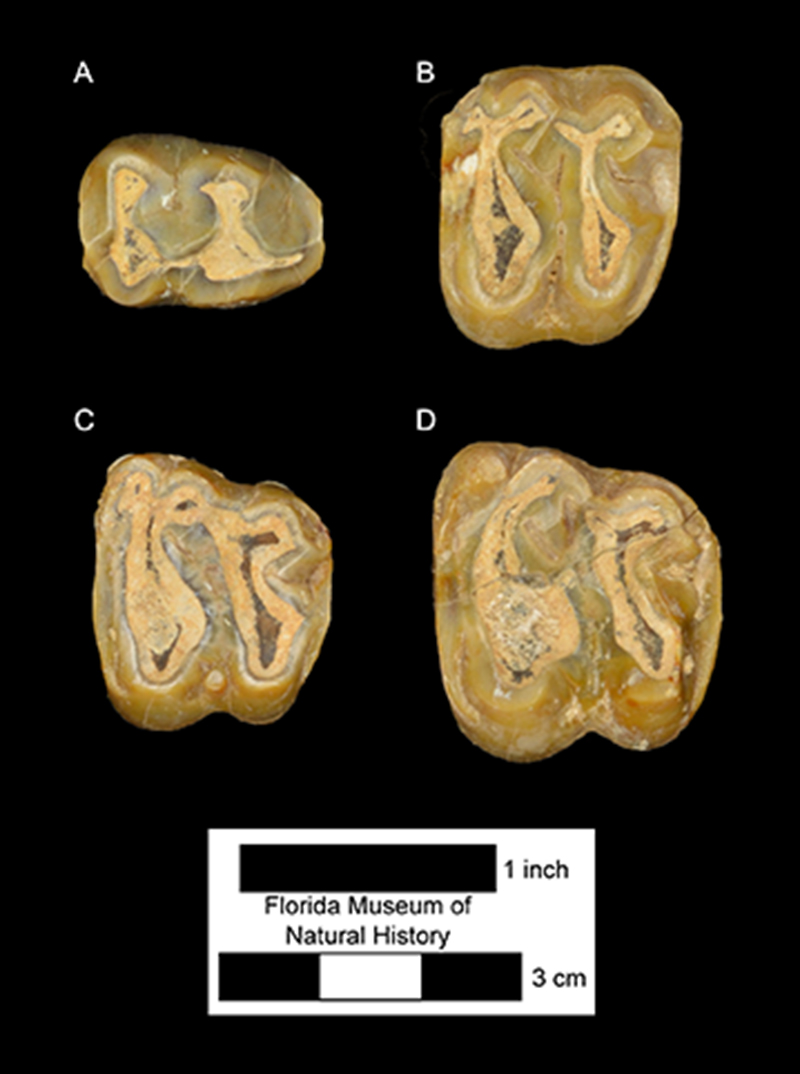

Overall the teeth of Tapirus webbi are very similar to other species in the genus. On average, molar width relative to length is narrower in Tapirus webbi than in species from the Pliocene and Pleistocene of Florida. Over half of the upper premolars and molars bear a ridge (called a cingulum) on the posterior outside of the tooth crown; such a ridge is not present in Tapirus haysii and Tapirus veroensis.

Most of the features that are distinctive for this species are present on the bones of the skull. The interparietal bone has five or six sides (three sides in Pliocene and Pleistocene species of tapirs in Florida). The nasal bone is very long and thick. The posterior process on the lacrimal bone is shaped like a short spike (a broad flap in Pliocene and Pleistocene species), and the lacrimal has two large openings (foramina) that are both visible in lateral view. The large, well formed depression on the top of the skull (on the nasal and frontal bones) present in Tapirus polkensis, Tapirus lundeliusi, Tapirus veroensis, and Tapirus haysii, is much smaller, shallower, and limited to the outer edge of the nasal bone in Tapirus webbi. The lower jaw of Webb’s tapir is relatively shallow and has a more up-right ascending ramus than in Tapirus lundeliusi, Tapirus veroensis, and Tapirus haysii. Another difference is that the first metatarsal, which is a reduced, vestigial bone in tapirs and rhinos, wraps around the back of the foot and articulates with both the third and fourth metatarsals in Tapirus webbi. In Tapirus lundeliusi, Tapirus veroensis, and Tapirus haysii, the first metatarsal only articulates with the third metatarsal.

Sources

- Original Author: Richard C. Hulbert Jr.

- Original Completion Date: October 14, 2012

- Editor: Richard C. Hulbert Jr.

- Last Updated On: May 12, 2015

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant Number CSBR 1203222, Jonathan Bloch, Principal Investigator. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

Copyright © Florida Museum of Natural History, University of Florida