Thecachampsa americana

Quick Facts

Common Name: North American false gharial

Thecachampsa americana is a long-snouted crocodile that inhabited Florida from 13 to 6 million years ago.

Thecachampsa americana grew to around 6 meters long, slightly larger than its closest living ancestor, the modern false gharial (Tomistoma schlegelii), which lives in Malaysia and Indonesia.

Age Range

- Middle and late Miocene Epoch; Barstovian, Clarendonian, and early Hemphillian (Hemphillian 1 and 2) land mammal ages

- About 13 to 6 million years ago

Scientific Name and Classification

Thecachampsa americana Sellards, 1915

Source of Species Name: Although Sellards (1915) did not explicitly state the source of the species name, it clearly referred to the American continents, to emphasize its geographic origin because this was the first member of the subfamily Tomistominae to be named from either North or South America.

Classification: Reptilia, Diapsida, Archosauria, Crocodylomorpha, Crocodylia, Crocodylidae, Tomistominae

Alternate Scientific Names: Tomistoma americana, Gavialosuchus americanus, Thecachampsa antiqua sensu Myrick (2001), Megalodelphis magnidens.

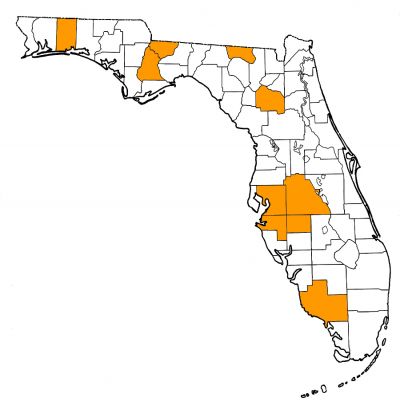

Overall Geographic Range

Eastern coast of the United States with occurrences in Florida and South Carolina. If conspecific with Tomistoma lusitanica and specimens referred to Thecachampsa antiqua, as proposed by Myrick (2001), then the distribution expands to include North Carolina, Virginia, Maryland, and New Jersey in North America, and Lisbon, Portugal in Europe (but see below). The type locality of Thecachampsa americana is the Amalgamated Phosphate Company Mine, near Brewster in Polk County, Florida (Sellards, 1915).

Florida Fossil Occurrences

Florida fossil sites with Thecachampsa americana:

- Alachua County—Gainesville Creeks Fauna (including Cofrin Creek, Gainesville High School Creek, Hogtown Creek, Little Hatchet Creek, and Rattlesnake Creek); Haile 1A; Haile 5A; Haile 5B; Haile 19A; Love Site; McGehee Farm

- Collier County—Owl Hammock Well

- Gadsden County—La Camelia Mine; Gunn Farm Mine (identification to species level tentative)

- Hamilton County—Suwanee River Mine; Occidental Phosphate Mine; Swift Creek Mine

- Hardee County—Hardee Complex Mine (C.F. Industries)

- Hillsborough County—Four Corners Mine; Kingsford Mine

- Liberty County—Langston Quarry 2

- Manatee County—Manatee County Dam Site

- Okaloosa County—Laurel Hill Pit 1

- Polk County—Achan Mine; Amalgamated Phosphate Company Mine; Brewster Mine; Fort Meade Mine (Cargill); Fort Meade Mine (Gardinier); Hookers Prairie Mine, Agricola Road Site; Kingsford Mine; Nichols Mine; Palmetto Mine; Payne Creek Mine; Peace River Mine; Phosphoria Mine; Prairie Mine; Silver City Mine; Tiger Bay Mine

Discussion

Thecachampsa americana is a long-snouted crocodile that inhabited Florida during the middle and late Miocene. Among living species, it is most closely related to Tomistoma schlegelii (common name the false gharial), which lives in Malaysia and Indonesia. Both of them belong to the subfamily Tomistominae (Brochu, 1997, 2003, 2007; Vélez-Juarbe et al., 2007; Jouve et al., 2008; Brochu and Storrs, 2012). Tomistomine crocodylids are not considered by these authors to be closely related to the true gharial (or gavial), which is placed in a separate family Gavialidae, despite the similarity in appearance due to its long snout, or rostrum. Thecachampsa americana attained lengths of about 6 meters (estimate based on Sereno et al., 2001:fig. 4B), and although it was slightly larger than the modern Tomistoma schlegelii, it was not among the largest crocodiles that existed during the Tertiary. It coexisted in Florida with species in the genus Alligator, a crocodilian that lived (and still lives) in the region.

Until recently, Thecachampsa americana was most often placed in the genus Gavialosuchus (e.g., Erickson and Sawyer, 1996; Brochu, 1997; Jouve et al., 2008; Hastings et al., 2013). However, analyses of the evolutionary relationships of crocodilians by Brochu (2006, 2007), Vélez-Juarbe et al. (2007), and Brochu and Storrs (2012) have shown that Thecachampsa americana and the type species of the genus Gavialosuchus, Gavialosuchus eggenburgensis (Toula and Kail, 1885) from the Miocene of Austria, do not form a monophyletic group, and thus should not be in the same genus. The taxonomy here follows the cladogram published in Brochu and Storrs (2012), which recognized three species in the genus Thecachampsa: the type species, Thecachampsa antiqua (Leidy, 1852); Thecachampsa carolinense (Erickson and Sawyer, 1996) from the late Oligocene of South Carolina; and Thecachampsa americana from Florida.

A potential problem with the current taxonomic arrangement is the uncertainty behind the validity of Thecachampsa antiqua as a species. The type species for the genus Thecachapmsa was described by Leidy (1852) based on two teeth, fragments of two vertebrae, and a rib from Virginia, which are non-diagnostic elements. If the species is not valid, then the genus name will also be invalid and would need to be replaced. A much more complete specimen from the Calvert Formation in Virginia (USNM 25243) was referred to Thecachampsa antiqua and figured by Myrick (2001) but was not described in detail. A more thorough investigation is needed to determine if Leidy’s species name is in fact valid. This would require a type specimen that contains diagnostic characters that distinguish the species from other crocodilians. Until such a publication, the name Thecachampsa americana is used here for the long-snouted crocodile of the Miocene of Florida.

As noted above, Myrick (2001) proposed that “Gavialosuchus americanus” (=Thecacampsa americana), Tomistoma lusitanica, and Thecachampsa antiqua represented a single species, with the latter name having priority. However, the phylogenetic analyses of Brochu (2007), Vélez-Juarbe et al. (2007), and Brochu and Storrs (2012) do not place Tomistoma lusitanica in the same clade as the other two, meaning that it is closely related enough to warrant the same genus name as the other two species. Furthermore, Thecachampsa antiqua and Thecachampsa americana were depicted as two distinct species by Brochu and Storrs (2012).

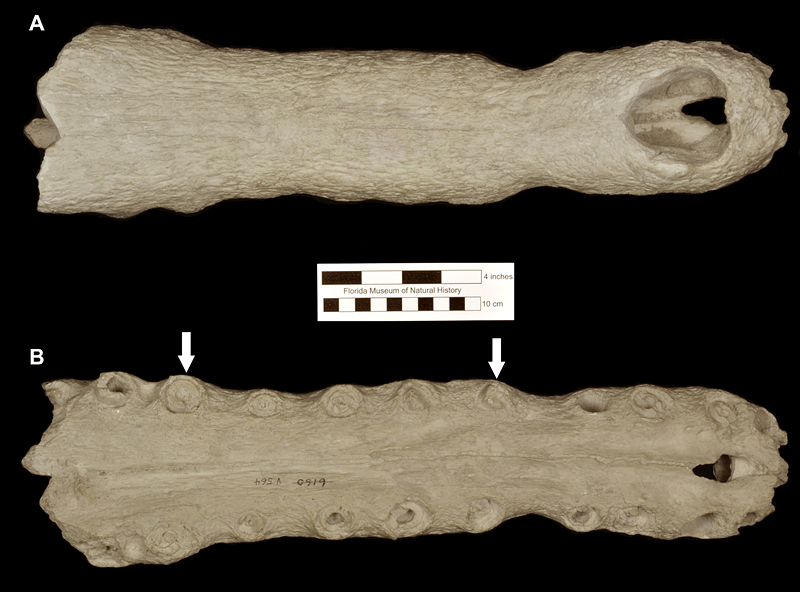

The type specimen of Thecachampsa americana (Fig. 2) was found in a phosphate mine of the Amalgamated Phosphate Company, and presented to the Florida Geological Survey by the general manager of the mine, Anton Schneider. Sellards (1915) originally named the Florida specimen as Tomistoma americana on the basis of fragments of a skull and jaw. This was the first species to be named on the basis of fossils from the Central Florida phosphate mines. Using new and more complete specimens, Mook (1921, 1924) redefined the Florida species and reassigned it to the genus Gavialosuchus. Within the stratigraphic sequence of the deposits from the Central Florida Phosphate Mining District (“Bone Valley”), fossils of Thecachampsa americana have been collected from the middle and late Miocene deposits; none are known to occur in deposits that represent the early Pliocene Palmetto Fauna.

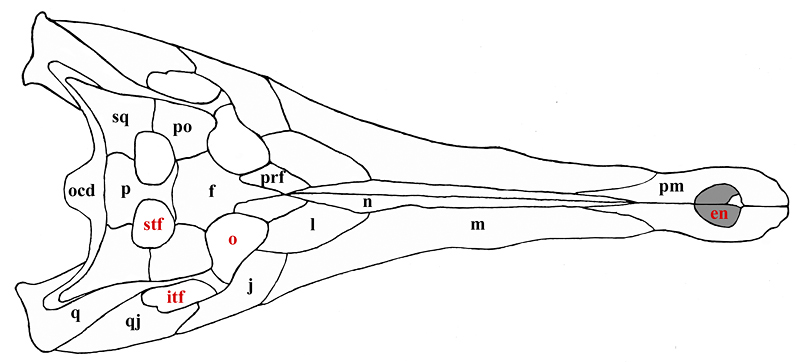

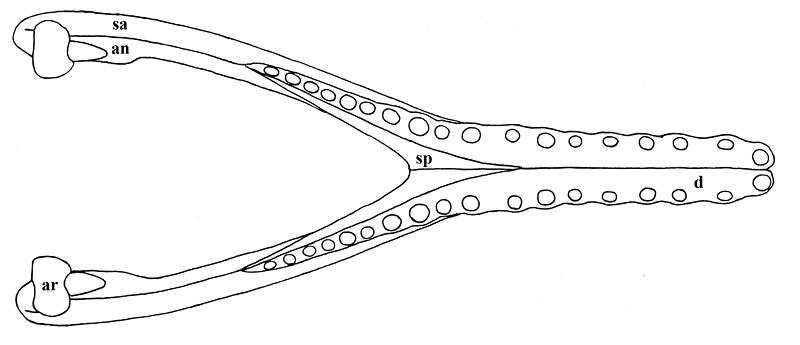

Some of the features that characterize Thecachampsa americana are the staggered expansion of the snout at the first and fifth maxillary teeth (Fig. 2), not gradually as in Tomistoma schlegelii. The fifth maxillary tooth is much larger than the fourth as in most crocodylids. Thecachampsa americana has five premaxillary teeth, and fourteen maxillary teeth, different in this respect to Tomistoma schlegelii that has four premaxillary teeth and sixteen maxillary teeth. The orbits are elongate and widely separated. The supratemporal fenestrae are large and very close together. The cranial table is broad, concave, and has parallel sides which give it a rectangular shape. The premaxillo-nasal suture is almost four times as long as it is in Tomistoma schlegelii (Fig. 3).

In the mandible, there are eighteen large, widely spaced teeth in the dentary. The long mandibular symphysis extends to between the eleventh and twelfth teeth (Fig. 4). The splenials make up an important part of the posterior portion of the symphysis.

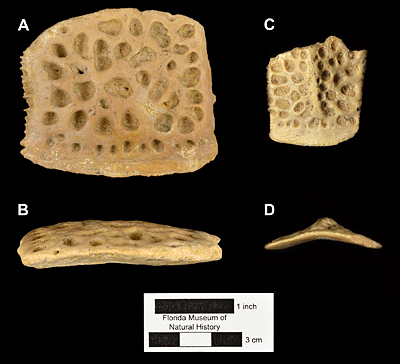

Osteoderms of Thecachampsa americana vary in size depending of the age of the individual and the position in the body; they possess sutural edges for the contact with adjacent osteoderms, and are all flat; this last characteristic allows paleontologists and herpatologists to differentiate between the osteoderms of Thecachampsa americana and those of the genus Alligator whose osteoderms bear a marked ridge on the dorsal surface (Fig. 5). The teeth of Thecachampsa americana are generally taller and relatively more slender than those of the genus Alligator, making most isolated teeth found as fossils in Florida identifiable to the genus level.

Gavials and tomistomines (‘false gharials’) are classically considered to have had different evolutionary histories based on morphological analysis of extinct and extanttaxa (Brochu, 1997, 2003, 2006, 2007; Jouve et al., 2008; Shan et al., 2009; Brochu and Storrs, 2012). However, there is a conflict between this interpretation and the one followed by molecular biologists who place tomistomines and gavials as sister clades (Harshman et al., 2003). Regardless of their phylogenetic history, both groups were more diverse and widely distributed in the past when compared to related species of today. This is clear in that each group is currently represented by only one species today (Tomistoma schlegelii and Gavialis gangeticus, respectively) and are restricted to limited areas in Asia.

Thecachampsa americana, as well as several other fossil tomistomines, are found in estuarine or coastal marine deposits suggesting that even though the extant species Tomistoma schlegelii only inhabits freshwater lakes and rivers, in the past this clade was able to tolerate marine environments and even dispersed across marine barriers.

The co-occurrence of Gavialosuchus americanus with Alligator sp. at the Love Site and McGehee Farm suggests ecological separation. Indeed, differences in their snout morphologies and teeth suggests different feeding preferences. Alligators are classified as dietary generalists, while long-snouted crocodiles, such as tomistomines and gavialids, have a piscivorous diet (Brochu, 2001, 2003).

Sources

- Original Author(s): Julia V. Tejada Lara

- Original Completion Date: October 05, 2012

- Editor(s) Name(s): Richard C. Hulbert Jr. and Natali Valdes

- Last Updated On: March 3, 2015

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant Number CSBR 1203222, Jonathan Bloch, Principal Investigator. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

Copyright © Florida Museum of Natural History, University of Florida