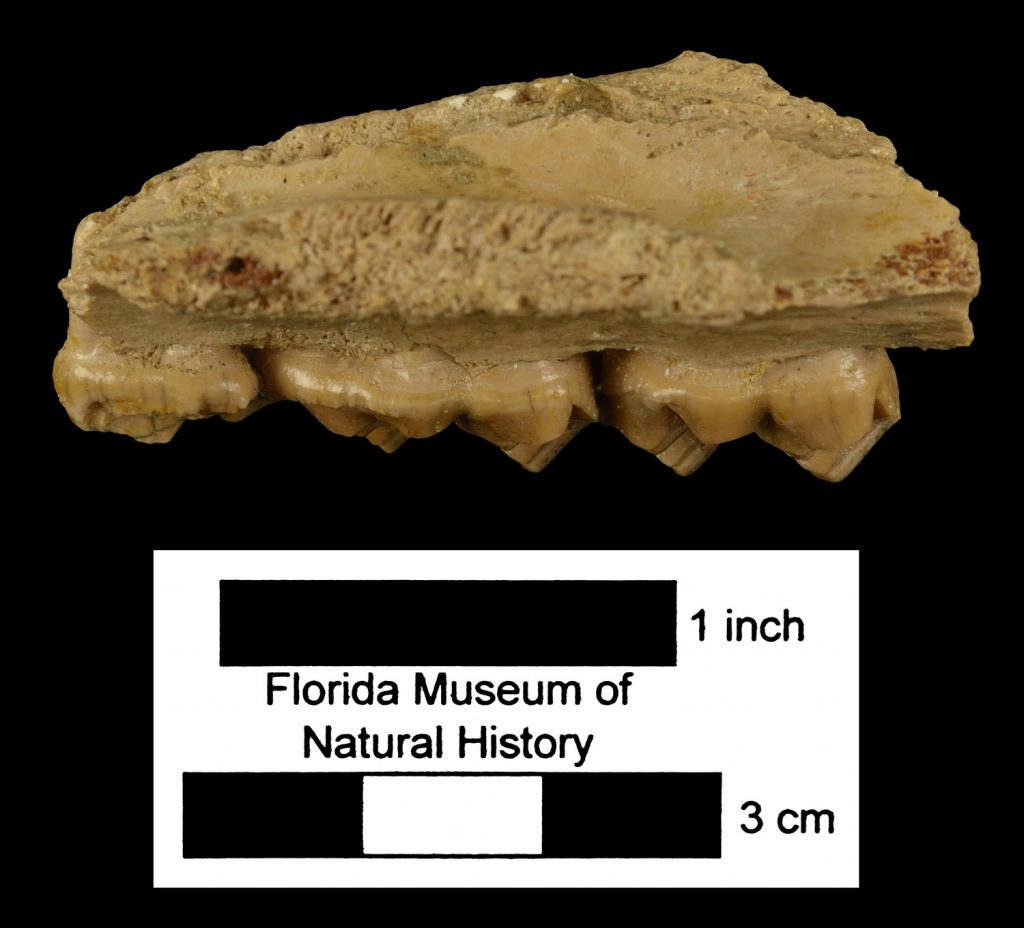

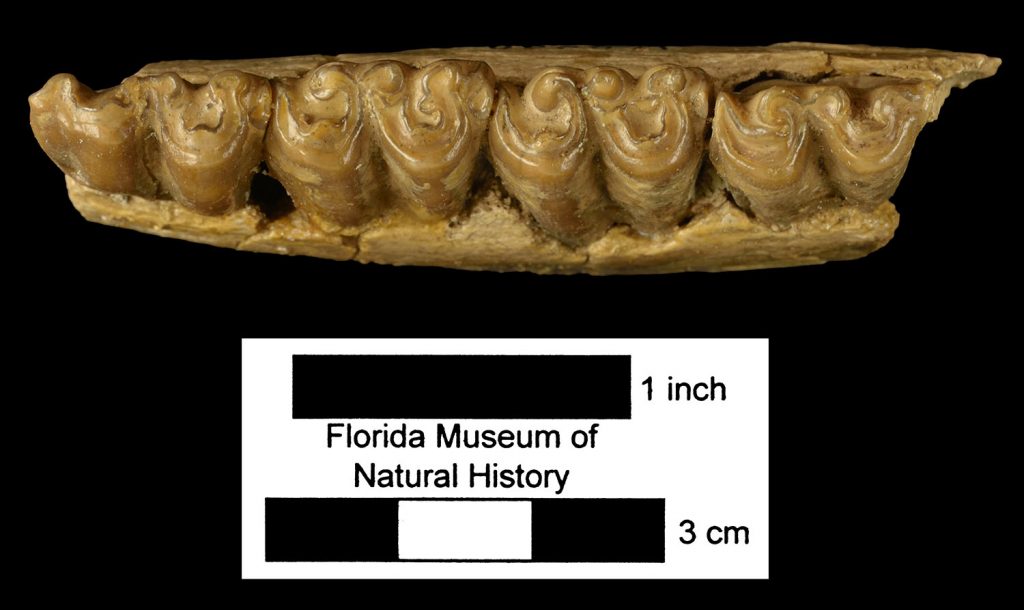

Merychippus represents a milestone in the evolution of horses. Though it retained the primitive character of 3 toes, it looked like a modern horse. Merychippus had a long face. Its long legs allowed it to escape from predators and migrate long distances to feed. It had high-crowned cheek teeth, making it the first known grazing horse and the ancestor of all later horse lineages.

Where & When?

Fossils of Merychippus are found at many late Miocene localities throughout the United States. Species in this genus lived from 17-11 million years ago

Did the “ruminant horse” ruminate?

The ruminant digestive system is a slow, but highly efficient method of processing vegetation. So far as we know, no living horse, rhino, or tapir has ever had such a system, so it is unlikely that the “ruminant horse” ruminated. Merychippus got its name because the crests of the teeth of reminded Professor Leidy — the scientist who named this genus — of the teeth of ruminants.

Ruminant ungulates, hoofed mammals such as cows, sheep and goats, swallow vegetation that is then processed in one or more of the “foregut” chambers, so-called because they occur before the “true” stomach, known as an “abomasum.” The animal then ejects the partially digested food back into the mouth to chew again. This step is called “chewing its cud.” This twice-chewed vegetation is swallowed once more where it is finally processed in the true stomach.

Horses are called “hind-gut fermenters” because they have a digestive pouch in the intestine, or “caecum,” behind the stomach. Microbes in the caecum break down the vegetation so that energy and nutrients can be obtained by the horse.

Paleontologists almost never find fossilized digestive tracks and so can only make educated guesses about the digestive physiology of extinct animals.