by W. Mark Whitten, Florida Museum of Natural History, Gainesville FL and Colette C. Jacono, United States Geological Survey, Gainesville FL

Abstract

Marsilea ferns (water clover) are potentially invasive aquatic and wetland plants that are difficult to identify to species because of subtle diagnostic characters, sterile specimens, and unresolved taxonomic problems. We utilized DNA sequencing of several plastid regions to attempt to “fingerprint” Marsilea specimens from the southeastern U.S. to provide more accurate identifications. Currently, seven species are recognized from the eastern U.S., 6 of which have been found in Florida. Our data show that Florida specimens previously identified as M. oligospora (Jacono and Johnson 2006) are not true M. oligospora (native to the western U.S.), and instead may represent either an unknown introduced species or an undescribed native species.

Molecular data conflict with the morphological characters for distinguishing M. vestita, M. macropoda, and M. nashii. The molecular data reveal two clades within this species complex: 1. A western U.S/Mexican clade; and 2. an eastern U.S./coastal plain clade. This DNA/morphology discordance suggests that these taxa may have hybridized extensively or may represent only one variable species; either case warrants reexamination of the species level-taxonomy of the group. DNA data clearly distinguish all other species of introduced Marsilea, and DNA sequencing is valuable as a tool for identification of sterile Marsilea specimens.

Introduction

Marsilea (Water-Clover) is a genus of aquatic ferns that is increasingly being found as invasive in Florida and the Southeast. Marsilea (ca. 50 spp.) occur worldwide as two ecological types 1) true aquatic species with glabrous leaves that inhabit permanent water bodies and 2) semi-aquatic species with hairy leaves that prefer fluctuating wetland habitats and prevail through seasonal extremes in wet and dry periods. Florida’s lakes and wetlands provide habitat for both types and currently host at least six species of both ecological types, all of which have been hypothesized as introduced.

The Water-Clovers bear few dependable morphological characters on which to base traditional identification. Morphological plasticity is widespread, and sporocarps, an important identification feature, are commonly absent in field populations. Because identification of Marsileabased upon morphology is so problematic, aquatic plant managers need more reliable tools for identification. Without objective methods of identification, managers cannot make decisions about the probable identity and origin of introduced species and how to manage populations. In this study, we use DNA sequences of four plastid regions (rbcL, rps4, the rps4-trnS spacer, and the trnL-F spacer) to aid in identification of Marsilea specimens. The recent molecular phylogeny of Marsilea (Nagalingum et al., 2007) provides a phylogenetic framework for comparison of sequences in GenBank with those from additional specimens.

Several populations of Marsilea in Florida (far from natural, western U.S. distributions) have uncertain identities. Of primary interest are historical specimens, collected in the early 1890s, the identification of which has vacillated from M. vestita, an introduction from the western U.S. (Ward and Hall 1976) to M. ancylopoda, a rare and potentially extinct native species (FNA 1993). Plants in recently reported populations in three central Florida counties appearing identical to plants from the historic sites were identified as M. oligospora, a semi-aquatic North American species endemic to the northern fringe of the Great Basin (Jacono and Johnson 2006). Nevertheless, variation was noted between the Florida and the Great Basin material and it was difficult for the authors to speculate how a geographically restricted plant with no known economic value may have become established in central Florida over 100 years ago.

At the same time, invasive plant managers are interested in initiating herbicide practices on pest populations of Marsilea. One site of particular concern is Emeralda Marsh, a 1,500 acre restoration unit bordering Lake Griffin, Lake County, FL where M. oligospora appears to be increasing in wetlands where the naturally fluctuating hydrologic regime is being restored. Molecular data may provide a more confident determination of these specimens and help to resolve whether these populations are introduced weeds to be targeted for herbicide treatment or if they are a native component of natural wetlands.

Our specific objective is to provide molecular evidence to support or refute morphological identification and region of origin of the central Florida populations. Such evidence will provide a more sound basis for future pest plant listing and for responsible management practices. However, the laboratory procedures to be developed are a modest investment with wider application than identification of a single species. The method will serve as a screening protocol for well established, new and potentially invasive species of this difficult and typically sterile genus. In this project we surveyed all known populations of Marsilea within Florida using several molecular markers and compared them to all U.S. and Caribbean species, as well as Marsilea species common in the aquatic plant trade that are becoming established in the Southeast. These data will provide a baseline for evaluating the identity and nativity of species in Florida and for distinguishing future introductions of Marsilea.

Methods

Appendix 1 presents a list of voucher specimens sampled. Samples were taken from herbarium specimens (with permission) from various herbaria. Because Florida collections of M. oligospora were hypothesized to be introductions from the western US (Jacono and Johnson 2006), we included specimens from several western herbaria (from the vicinity of the type locality). Leaf samples (ca. 25 mm2) were ground using a tissue mill and extracted using a modified version of the 2x CTAB procedure of Doyle and Doyle (1987) with exclusion of beta-mercaptoethanol and inclusion of 5 units of proteinase K to improve yield and quality of DNA. Primers for rbcL were designed to allow amplification and sequencing in two overlapping pieces, facilitating amplification from degraded total DNAs. Primers for rbcL are: rbcL F ATGTCACCACAAACAGAGACTAAAGC; rbcL intF TGAGAACGTAAACTCCCAACCATTCA; rbcL intR CTGTCTATCGATAACAGCATGCAT; and rbcL R GCAGCAGCTAGTTCCGGGCTCCA. The rps4 exon and the adjacent rps4-trnS spacer were amplified in one piece using the primers rps4F ATGTCCCGTTATCGAGGACCT and rps4R TACCGAGGGTTCGAATC. Primers for the trnL-F spacer (primers E&F) were those of Nagalingum et al. (2007). All amplifications utilized Sigma Jumpstart Taq polymerase and reagents (Sigma-Aldrich, Inc.) in 25 μl reactions with 3.0 mM MgCl2. Thermocycler conditions were: 94 C for 3 minutes followed by 37 cycles of 94 C for 30 s, 56 C for 30 s, 72 C for 2 min, with a final extension of 3 min at 72 C. PCR products were sequenced in both directions, using the Big Dye Terminator reagents on an 3130 automated sequencer following manufacturer’s protocols (Applied Biosystems, Inc.). Electropherograms were edited and assembled using Sequencher 4.8 (Genecodes Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA), and the resulting sequences were aligned manually. All sequences will be deposited in GenBank prior to publication. Analyses were performed using PAUP* version 4.0 b10 (Swofford, 2003) with Fitch parsimony (equal weights, unordered characters, ACCTRAN optimization and gaps treated as missing data. Heuristic searches consisted of 1000 random taxon addition replicates of subtree-pruning-regrafting (SPR) and keeping multiple trees (MULTREES) with the number of trees limited to 10 per replicate to minimize extensive swapping on islands with many suboptimal trees.

Results and Discussion

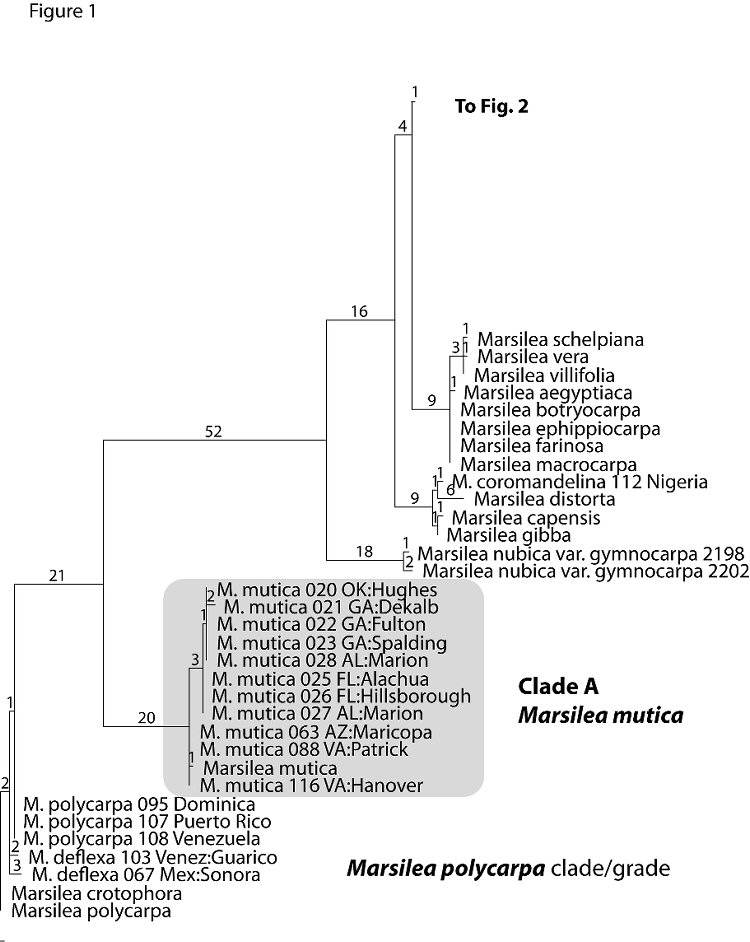

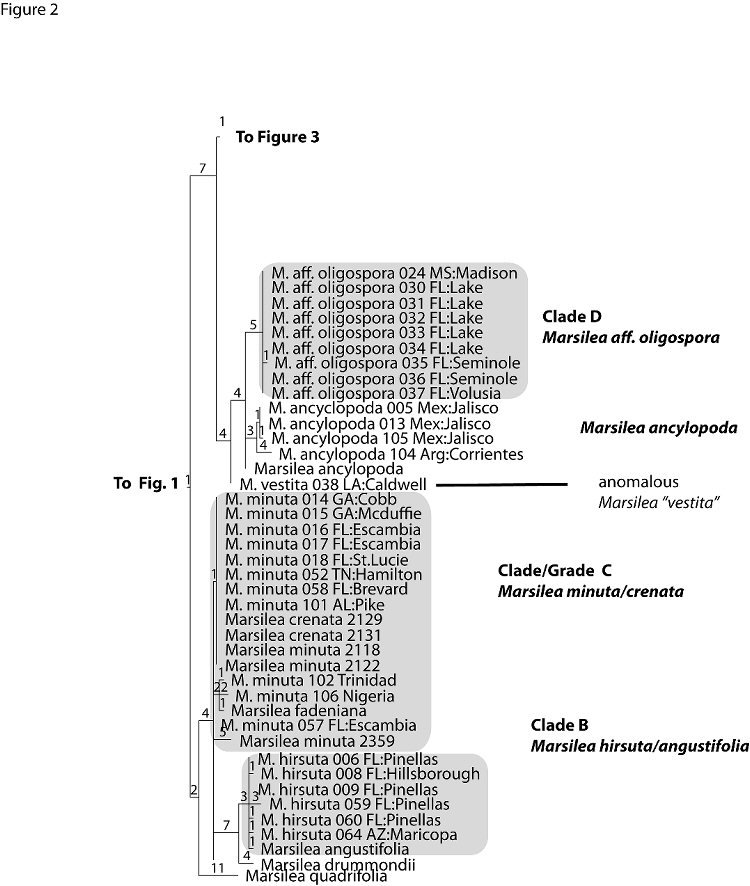

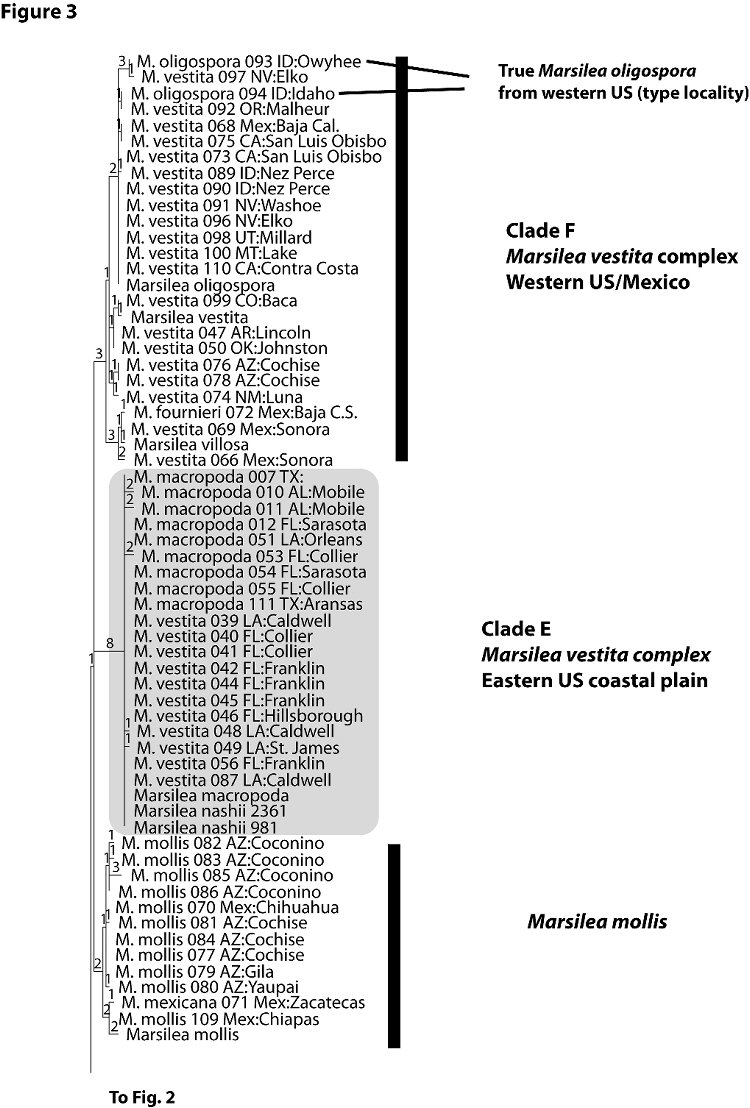

Figures 1-3 presents a randomly chosen single most parsimonious tree. The tree combines data in GenBank from the world wide taxonomic sampling of Nagalingum et al. (2007) with data generated from this study (Appendix 1). Individuals noted in full Latin binomial are from GenBank data. Individuals noted by “M.” followed by a species name and three digit number and locality, usually a state and county, are primarily U.S. collections sampled by us in this study.

The Florida collections of Marsilea fall into five distinct clades within the tree; these clades are highlighted in gray and labeled Clades A-E.

The DNA data revealed that numerous specimens sampled in this study (especially sterile ones) were misdetermined. DNA analysis was especially effective in clarifying the identification of sterile specimens of both North American and introduced origin and was equally effective with aquatic and semiaquatic ecotypes.

Little or no genetic variation among geographically distant introductions of the same species (eg. M. minuta, M. hirsuta) suggests a wide reaching water garden industry as the source of North American material.

M. mutica (clade A; Figure 1) is clearly distinct from all other taxa in terms of DNA distance. This parallels its morphology which is unique from all other taxa for its two-toned leaflets and petioles inflated at the apex to function as air bladders for floating leaves. Indigenous to Australia and New Caledonia, M. mutica may be the most popular species in the water garden trade. The SE US specimens plus one from Oklahoma form a clade distinct from specimens from Arizona and Virginia. This is suggestive of at least two distinct geographic origins for material introduced into the US.

Clade B (Figure 2) includes M. hirsuta, an Australian species introduced into Florida. Three Australian hairy leaved species (M. drummondii, M. angustifolia and M. hirsuta) form a clade distinct from the Australian glabrous leaved species, M. mutica. DNA data fail to distinguish M. hirsutafrom M. angustifolia. Morphologically, M. angustifolia differs from M. hirsuta in having smaller and more elongated leaves and smaller sporocarps (Aston 1973). These characters, however, are typically considered insufficient for species distinction within the genus Marsilea (Launert 1968). Our DNA data suggests that the taxonomic boundaries of these two species should be reexamined.

Clade C (Figure 2) consists of M. minuta (plus M. crenata, M. fadeniana). Samples from introductions in the southeastern U.S. appear more closely related to M. minuta from India, and to M. crenata, from Thailand and Indonesia than to M. minuta from Africa. A population of M. minuta introduced to Trinidad since at least 1982 is discrete from the southeast material and more closely related to M. minuta and M. fadeniana from Africa. As presently circumscribed, M. minuta is a geographically widespread species that needs further taxonomic clarification. Although not tested in this study, M. crenata, which has been reported as introduced to Hawaii is probably the same entity as M. minuta in the SE US. Johnson (1986) suggested that M. quadrifolia, long established in the northeastern U.S., may be close to M. minuta, but, based on the one specimen from Japan sampled in this study, this would not be the case. M. quadrifolia is the most temperate of the Marsilea species. Generally, introductions of M. quadrifolia are from earlier dates and are believed to have originated from Europe. Paradoxically, in Europe it is now a Red Data species, listed for its rarity and vulnerability to extinction.

Clade D (Figure 2) includes Florida specimens previously determined as M. oligospora by Jacono (thought to represent an introduction from the western US), but DNA data show that these specimens do not match any material tested or in GenBank. They are clearly distinct from specimens of “true” M. oligospora (Figure 3) from the western US (close to the type locality). The DNA data demonstrates that it is a distinct species, yet related to M. ancylopoda, a widely distributed neotropical species with which it was earlier misidentified (FNA 1993). The geographic range of this M. aff. oligospora plus the existence of Florida collections from the 1890s suggests an alternative hypothesis: that it may be a native species. Although the very recent expansion of the species at artificial and disturbed habitats seems to dispute this assumption, only greater sampling of species in the Caribbean and tropical Americas might reveal the true identity of M. aff. oligospora in Florida.

Clade E (Figure 3) consists exclusively of plants from the U.S. Gulf Coast and Florida, and includes specimens determined as either M. vestita, M. macropoda, or M. nashii (from GenBank). Although well accepted as distinct North American species, the morphological distinctions separating vestita and macropoda clearly do not agree with the molecular data presented here. The correct name for plants in this clade (probably M. macropoda or M. nashii) is yet to be determined, and will require comparison of sequence data with specimens from the type localities of these two species. Comparison with specimens noted earlier as putative hybrids between M. vestita and macropoda in Texas (Johnson 1986) should also prove informative. The demarcation of specimens into Clade E introduces the scenario that plants previously labeled vestita and macropoda and considered western NA introductions into Florida, may in fact represent an independent entity (or hybrid) that could be native in Florida. If this were the case, it may serve as indirect support for the Clade D entity (M. aff. oligospora) occurring as native to Florida.

Clade F (Figure 3) consists of specimens of M. vestita and M. oligospora from the western US and Mexico, and suggests that species boundaries and taxonomy of these taxa need to be reevaluated. The Hawaiian species M. villosa and a specimen determined as M. fourneiri also fall in Clade F. Clearly, the taxonomic relationships of M. vestita, its subspecies, and related species need to be reexamined. One possible explanation for the geographic distinction between clades E and F is that these species have hybridized (resulting in a single chloroplast type because of uniparental inheritance of chloroplasts); this hypothesis could be evaluated by sequencing of a suitable nuclear marker that is biparentally inherited. However, we know of no experimental or molecular evidence that Marsileas do hybridize in nature.

Conclusions/Recommendations

In light of the difficulties inherent to morphological identification of Marsilea, resource managers can opt for DNA analysis as a reliable tool in species identification. DNA analysis effectively determined sterile specimens of North American and introduced species at a minimal cost per sample. Results from DNA analysis also revealed a low level of genetic diversity among collections of geographically distant introductions of the same species, which indicates a wide reaching industry as a source of the eastern hemisphere species M. minuta, M. hirsuta, and M. mutica.

DNA results further indicate that Florida M. aff. oligospora should not be regarded as an introduced species nor targeted for eradication until more is known about its identity. If the entity represents an undescribed native species, its increase at restoration marshes could be a sign of the return of more natural hydroperiods and ecological dynamics.

Discrepancies demonstrated by DNA analysis in the taxonomic relationships among specimens labeled M. vestita or M. macropoda has in the past been addressed by designation of morphological subspecies. In light of the geographical patterns found in our study, reexamination of this species group may reveal that a hybrid of the two, or a third species, could be native in Florida. If this were the case, it may further support the nativity of M. aff. oligospora in that state.

Literature Cited

- Aston, Helen 1973. Aquatic Plants of Australia: A guide to the identification of the aquatic ferns and flowering plants of Australia, both native and naturalized. National Herbarium of Victoria, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne.

- Chase, M.W., R. S. Cowan, P. M. Hollingsworth, C. van den Berg, S. Madriñán, G. Petersen, O. Seberg, T. Jørgsensen, K. M. Cameron, M. Carine, N. Pedersen, T. Hedderson, F. Conrad, G. Salazar, J. Richardson, M. Hollingsworth, T. Barraclough, L. Kelly and M.Wilkinson. 2007. A proposal for a standardised protocol to barcode all land plants. Taxon 56(2):295-300.

- Doyle, J. J. and J. L. Doyle. 1987. A rapid DNA isolation procedure for small quantities of fresh leaf tissue. Phytochemical Bulletin 19: 11-15.

- (FNA) Flora of North America Editorial Committee (eds.). 1993. Flora of North America North of Mexico. Volume 2. Pteridophytes and Gymnosperms. Oxford University Press, New York.

- Jacono, C. C. and D. M. Johnson. 2006. Water-clover Ferns, Marsilea, in the Southeastern United States. Castanea 71(1):1-14.

- Johnson, D.M. 1986. Systematics of the new world species of Marsilea (Marsileaceae). Systematic Botany Monographs 11:1-87.

- Launert. E. 1968. A monographic survey of the genus Marsilea Linnaeus. Senckenbergiana Biologica 49:273-315.

- Nagalingum, N. S., H. Schneider, and K. M. Pryer. 2007. Molecular phylogenetic relationships and morphological evolution in the heterosporus fern genus Marsilea. Systematic Botany 32:16-25.

Figure 1. Base of single most parsimonious tree for combined molecular data set.

Figure 2. Mid-portion of single most parsimonious tree for combined molecular data set.

Figure 3. Terminal clades of single most parsimonious tree for combined molecular data set

Appendix 1. Specimens sampled for DNA analysis in this study.

DNA numbers (column 1) correspond to three-digit numbers following taxon names in figures 1-3. Some specimens failed to amplify or sequence cleanly, and are not represented in the tree.