The Taínos were among the most densely settled complex pre-state, sedentary societies in the Americas.

Culture History

Population estimates for the people living in the Caribbean in 1492 have varied enormously, and the debate over the number of Taíno living in Hispaniola when Columbus arrived remains unresolved. Estimates have ranged from 100,000 to more than 1,000,000, however archaeological surveys of the region and increasing information about village size and distribution suggests that a figure closer to the higher estimates rather than the lower ones might be more accurate.

Most researchers agree that the cultural ancestry of the Taínos can be traced to Arawakan-speaking people living along the Orinoco River in South America. At about 1,000 BC, these people, known to archaeologists as “Saladoid” were living in large settled towns, cultivated manioc and corn, and made elaborate painted pottery. It is thought that they migrated into the Caribbean, reaching as far as Eastern Hispaniola by about 250 BC, carrying and continuing their traditions of agriculture and pottery-making, as well as the production of elaborate carved stone and shell pendants and figurines thought to have had ritual significance.

After about 250 BC, the Saladoid people appear to have greatly diminished their geographic expansion, and by about AD 600 appear to have developed instead a new style of cultural expression in response to local conditions and populations. This new tradition is known archaeologically as Ostionoid. The Ostionoid tradition was characterized by larger populations and the expansion of settlements into a wider range of ecological settings than in earlier periods. Ostionoid peoples practiced agriculture in raised mounds (conucos), and developed an elaborate and distinctive artistic expression in pottery, bone, shell and stone. In many Ostionoid towns they also constructed planned open spaces for ball courts or other ritual functions.

The Taíno

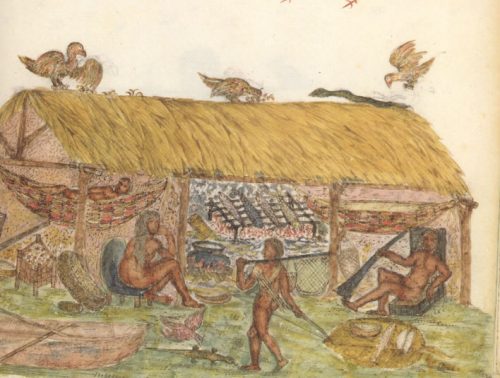

The Taíno of the Greater Antilles represented the last stage of the Ostionoid cultural tradition. By about AD 1100-1200, the Ostionoid people of Hispaniola lived in a wider and more diverse geographic area than did their predecessors; their villages were larger and more formally arranged, farming was intensified, and a distinctive material culture developed. They developed rich and vibrant ritual and artistic traditions that are revealed in Taíno craftsmanship in using bone, shell, stone wood and other media. Social stratification is thought to have become more pronounced and rigid during this period as well.

This stage of intensification and elaboration after AD 1100 is known as “Taíno”. The Taíno people, as characterized by archaeologists, were not a unified society, and have been categorized into subdivisions according to the degree of elaboration in their artistic and social expression. The Central or “Classic” Taínos are identified with the most complex and intensive traditions, and are represented archaeologically by “Chican-Ostionoid” material culture. They occupied much of Hispaniola, including En Bas Saline. The “Western” Taíno occupied central Cuba, Jamaica, and parts of Hispaniola, and , are also associated archaeologically with the “Ostionoid-Meillacan” material tradition. The Lucayan Taíno lived in the Bahamas, and the “Eastern” Taíno are thought to have lived in regions of the Virgin Islands and the Leeward Islands of the Lesser Antilles. As many archaeologists have emphasized, however, the Taíno were but one of the recognizable cultural groups in the Caribbean at the time of contact. They co-existed and interacted with other Ostionan peoples and perhaps even Saladoid-influenced Archaic peoples, such as the Guanahatabey of Cuba and the Caribs of the Lesser Antilles.