More than 250 years ago, enslaved Africans risked their lives to escape English plantations in Carolina and find freedom among the Spanish living at St. Augustine.

Battling slave catchers and dangerous swamps, they helped establish the first American underground railroad more than a century before the Civil War. Courageous Africans and their Native American allies shuttled runaways southward, rather than to the north, as the later railroad would. In Florida the Spanish freed the fugitives in return for their service to the King and their conversion to the Catholic faith. The Spanish were glad to have skilled laborers, and the freedmen were also welcome additions to St. Augustine’s weak military forces. In 1738 the Spanish governor established the runaways in their own fortified town, Gracia Real de Santa Teresa de Mose, about two miles north of St. Augustine, Florida. Mose (pronounced “Moh- say”) became the first legally sanctioned free Black town in the present-day United States, and it is a critically important site for Black American history. Mose provides important evidence that Black American colonial history was much more than slavery and oppression. The men and women of Mose won their liberty through great daring and effort and made important contributions to Florida’s multi-ethic heritage.

From 1986-1988 a team of specialists headed by Dr. Kathleen Deagan of the Florida Museum of Natural History carried out an archaeological and historical investigation at Ft. Mose. Their discoveries show that African Americans played important roles in the rivalry and confrontations between England and Spain in the colonial Southeast. The people of Mose were guerrilla fighters who made politically astute alliances with the Spaniards and their Native American allies, and waged fierce war against their former masters. The Black militia fought bravely alongside Spanish regulars to drive off the English and their allied Native American forces who attacked St. Augustine in 1740, and the Black troops also fought in the Spanish counter-offence against Georgia two years later.

The men and women who formed the community at Mose are no longer anonymous. Centuries-old documents recovered in the colonial archives of Spain, Florida, Cuba, and South Carolina by historian Dr. Jane Landers tell us who lived in Mose and something about what it was like to live there. We know that in 1759 the village consisted of twenty-two palm thatch huts which housed thirty-seven men, fifteen women, seven boys and eight girls. These villagers attended Mass in a wood church where their priest also lived. The people of Mose farmed the land and the men stood guard at the fort or patrolled the frontier. Most of the Carolina fugitives married fellow escapees, but some married Native American women or enslaved people living in St. Augustine.

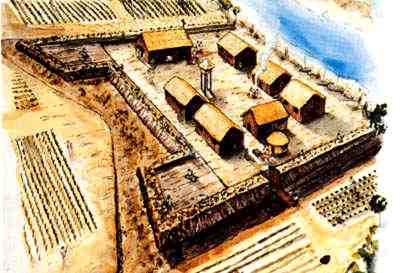

Archaeology has filled in some of the details about daily life at Mose. In the first season’s excavation archaeologists uncovered the remains of the fort itself, with its moat, clay-covered earth walls and wooden buildings inside the fort. They also found a wide variety of artifacts; military items such as gunflints, flattened bullets, metal buckles and hardware; household items such as thimbles, nails, ceramics, and glass bottles; food items such as burned seeds and bone, and even a hand-made St. Christopher’s medal.

The villagers came from many different tribal and cultural groups in West Africa and were taken as slaves to English Carolina. While struggling to gain their freedom they had extensive contact, both friendly and hostile, with many Native American peoples, and ultimately settled among the Spanish. How much of the way of life at Mose was African?

How much was Spanish? How much was Native American or English? Archaeologists are looking for the answers to these questions and other questions. Whatever the answers might be, the archaeological investigation of Ft. Mose is helping to document the critical, and previously unrecognized role of African Americans on the colonial frontier, and produce a better understanding of how various ethnic groups interacted in the Americas.

Mose stands as a monument to the courageous African Americans who risked, and often lost, their lives in the long struggle to achieve freedom. It is the only site of its kind in the United States, and is a precious and valuable part of our state and national patrimony. The Florida State Legislature, with the encouragement of Representative Bill Clark and Florida’s Black Legislative Caucus, has supported the ongoing research at Mose, and has approved acquisition of the site in order to protect and preserve it. Thanks to their efforts Ft. Mose was named as a National Historic Landmark in 1995, and is an important element in Florida’s Black Heritage Trail.

You can learn more about Ft. Mose in Ft. Mose, Colonial America’s Black Fortress of Freedom by Kathleen Deagan and Darcie MacMahon (University Press of Florida, Gainesville. 1995), and by visiting the Ft. Mose Historical Society web site at http://www.fortmose.org/.